Honor allows Weiping Tang and Jiaoyang Jiang to pursue new research opportunities

By Katie Gerhards & Katie Ginder-Vogel

Every year, an elite group of University of Wisconsin–Madison faculty members is honored with awards and professorships supported by the estate of William Vilas, former senator, UW regent, and professor. The chosen faculty members display teaching excellence and a high degree of research creativity, evidenced by numerous publications and national and international renown.

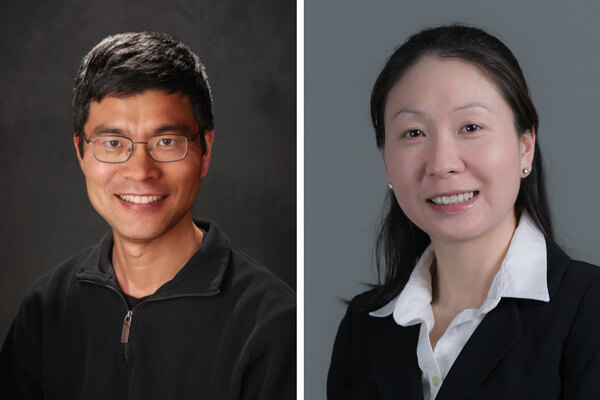

This year, two of the honored faculty members are from the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Pharmaceutical Sciences Division: Janis Apinis Professor Weiping Tang is receiving a Vilas Mid-Career Investigator Award, and Assistant Professor Jiaoyang Jiang the Vilas Early-Career Investigator Award.

Tang and Jiang — who were selected for the honor based on nominations and recommendations from Professor Ron Burnette, chair of the Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, and Dean Steve Swanson — will also receive flexible funding to pursue new research directions in their labs.

The School’s two 2019 honorees are in good company: Professor Richard Hsung, Kremers Distinguished Chair, earned the Vilas Distinguished Professor Award in 2017, and Charles Melbourne Johnson Distinguished Chair and Professor Lingjun Li and Professor Jeff Johnson, both became Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professors in 2015.

Although they have different areas of expertise, Tang and Jiang have each gotten to where they are today by relentlessly pursuing one thing: answers.

Weiping Tang: Curiosity-driven

“I didn’t get the chance to play with Legos when I was little,” Tang jokes. So today, he’s fulfilling that urge on a molecular level.

“We create and find new ways to put multiple molecules together, and then they have the potential to cure diseases,” says Tang, who is also director of the School’s Medicinal Chemistry Center.

In particular, the Tang Lab focuses on drug discovery, medicinal chemistry, and chemical biology. He and his team of interdisciplinary researchers are currently working on selective degradation of disease-causing proteins and new methods to improve the efficiency of carbohydrate synthesis.

One half of his research group is exploring how to efficiently make carbohydrates, which are as important as nucleic acids and proteins for life, yet the synthesis of carbohydrates lags far behind that of nucleic acids and proteins. Meanwhile, the other half is designing small molecules to specifically degrade disease-causing proteins, which have immense potential to become novel therapeutics for the treatment of diseases without any approved drugs.

“We’re interested in building a platform to collaborate with biologists on the UW–Madison campus,” says Tang. Many biologists are focused on studying one particular disease in-depth, while the technology Tang is developing will work with a variety of different proteins and diseases, so the potential for valuable partnerships is broad.

“Genetic tools, such as CRISPR and short interfering RNA, are extremely useful across all biological areas these days, and what we’re developing is complimentary to these tools,” he says. “The genetic tools modify protein expression indirectly on the DNA or RNA levels. In these cases, it takes a long time to see the effect on proteins, from days to weeks. Instead, what we’re doing is using small molecules to directly remove disease-causing proteins, which can yield the effect in minutes to hours.”

Essentially, Tang is producing a bridge molecule that will bring two otherwise unrelated proteins together to allow one of the proteins to tag the other for destruction. “It’s the chemist’s version of CRISPR-CAS9 technology,” he says.

This research will lay the foundation for the future development of drugs to treat many different types of cancers, infectious diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, and other diseases linked to dysregulation of proteins. Many of these diseases cannot be treated by conventional small molecule drugs.

With the new technology, Tang’s research group has developed several generations of degraders for HDAC6 (histone deacetylase 6), a protein linked to cancers and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, which he has been researching since he was a postdoctoral scholar at Harvard University. His discovery of HDAC6 selective inhibitor WT161 when he was a postdoc led to the development of two clinical candidates, ACY1215 and ACY241, which have entered into multiple phase I and phase II human clinical trials for the treatment of cancers.

In the past two years, his lab has landed three major grants from the National Institutes of Health: a U01 to streamline the synthesis of complex oligosaccharides, an R01 to study small molecule tools that can downregulate proteins causing hypercholesterolemia, and an exploratory R21 to create a new type of chemistry for carbohydrate synthesis. In 2018, he received a UW2020 grant on behalf of the Medicinal Chemistry Center to purchase an instrument that uses a micro-temperature gradient for a rapid and sensitive analysis of the strength of molecular interactions, which is another tool medicinal chemists can use to foster collaborations across campus.

“We’re interested in building a platform to collaborate with biologists on the UW–Madison campus.” –Weiping Tang

“We have a number of instruments available on campus, but nothing really comparable to this,” he says. “This will help us bring the medicinal chemists here together with the biologists throughout the rest of campus.”

His research pace has been so aggressive and successful that he was recognized in 2016 by Angewandte Chemie International Edition, a top chemistry research journal with an impact factor of 12, for his prolific publishing pace of one Angewandte Chemie paper per year in the past 10 years — a pace he has since maintained.

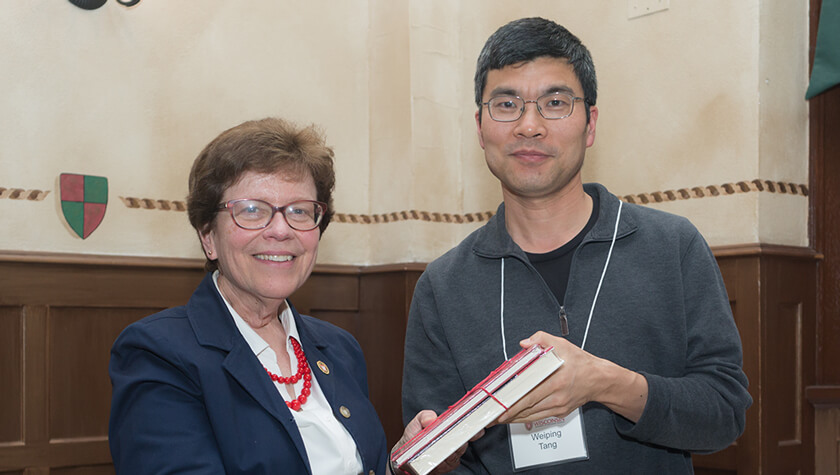

Through the Vilas Mid-Career Investigator Award, Tang is adding a lab manager with a master’s degree in biomedical engineering to his lab, setting the group up to explore more new horizons.

With the addition of this lab member, Tang plans to take the program in new directions by developing the capability to create and screen billions of novel DNA-barcoded compounds derived from biological systems, such as bacteriophage, to identify hits for the development of therapeutics through collaborations with other researchers at UW.

“It’s still chemistry, building peptide and peptidomimetic libraries for screening, but using phage, which requires a different skill,” he says. “The Vilas award provides the opportunity to explore new directions and new ways to produce potentially bioactive small molecules.”

Learn more about the research in the Tang Lab.

Jiaoyang Jiang: Chasing the unknown

“I’ve always been curious about unknown things,” Jiang says. “I have always wanted to find the answers. I want to answer challenging questions and explore the unknown.”

That’s why Jiang’s research focus has continually evolved in each phase of her career, which has earned her numerous publications and accolades, including the 2019 David Y. Gin New Investigator Award from the American Chemical Society.

She knew she wanted a career in research since she was an undergraduate at the University of Science and Technology of China, where she studied chemistry.

“I worked in a chemistry lab, doing computational modeling of chemical reactions and exploring unknown topics on my own,” Jiang explains. “I wanted to work in a wet lab next, so in graduate school, I switched my focus to biochemistry and studied how the enzymes in bacteria make the molecules that work in antibiotics.”

After earning her PhD in chemistry from Brown University, Jiang moved to Harvard Medical School to conduct postdoctoral research in chemical biology and glycobiology, using mass spectrometry and structural biology. That’s when she landed on her current research focus: exploring how one particular sugar molecule, derived from glucose, regulates many functions in the human body.

“After lunch, when food and drink enter the body, glucose gets converted into an activated form of sugar that can be added to proteins by enzymes, in a process called glycosylation, to change the activity of the proteins in our body,” explains Jiang.

Jiang is specifically looking at one curious pair of enzymes, OGT and OGA, which are very atypical in that they’re the only two enzymes that can make these changes on thousands of proteins inside our cells.

“The major question is, how can a single pair of these enzymes modify, or reverse modify, and regulate thousands of proteins’ functions in diverse biological processes?” says Jiang. “It’s a compelling question that attracted me.”

The Jiang Lab currently holds two major R01 grants from the National Institutes of Health to further this research: one to develop new tools to bind to both OGT and its protein targets during the sugar transfer process, and the other to expound upon her success as one of the first researchers to crystalize OGA’s structure by exploring the molecular signatures of OGA dysregulation in disease. The answers she uncovers will help inform treatments for a range of conditions, including cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and some autoimmune diseases.

When Jiang first started looking for academic jobs, her area of research was so new, few labs were exploring the topic, but now, more scientists are joining in. “More and more people are fascinated by this,” she says.

Since she joined the School’s faculty in 2013, the Jiang Lab has grown to include three postdocs and eight graduate students. The Vilas Early-Career Investigator Award will support new project development, which in turn will open new avenues for grant applications.

In addition to the augmented research capacity new members bring to her lab, Jiang also relishes the opportunity to mentor young researchers, whom she helps to prepare for future academic jobs.

“I constantly discuss new projects and papers with them and cultivate their analytical, writing, and presentation skills,” says Jiang. “We have weekly group meetings, and they write posters, manuscripts, and parts of grant applications, which gives them lots of practice.”

“Sharing our research with people who wouldn’t otherwise have the opportunity to do it makes us realize our research is valuable and can educate other people.” –Jiaoyang Jiang

The reach of her mentorship isn’t limited to UW–Madison students. When Jiang realized local community colleges didn’t have the facilities or lab equipment for students to do research, she invited Madison College students to join her lab as summer interns. Her first intern, John MacDonald, enjoyed his research experience so much that he decided to transfer to UW–Madison. He worked in her lab for more than two years and decided to pursue biochemistry in his graduate studies.

“Sharing our research with people who wouldn’t otherwise have the opportunity to do it makes us realize our research is valuable and can educate other people,” says Jiang.

Even for those she doesn’t mentor directly, Jiang still keeps her door open, and strives to help students who feel like they’re falling behind.

“When students who have come to office hours to ask for study tips send me an email about how they’ve improved or bump into me and express appreciation, I feel really proud,” she says. “One student who struggled last year came and talked to me every week. He recently caught me in the hall to say thank you, because he has grown so much and gotten a new job and more confidence. That’s one of my favorite parts of my job.”

Learn more about the biochemical mystery the Jiang Lab is solving.