27

February

By Katie Ginder-Vogel

“I’ve just been feeling so down and so anxious,” said the patient, an elegant woman in her 70s with a soft voice. “How long do you think it will take before I feel better?”

“That’s a really good question,” responded the pharmacist calmly, holding eye contact with her patient as they discussed the patient’s new antidepressant prescription. “It could be a few months, so it’s really important that you take this medication every day, and if you have a day when you’re just feeling really anxious, you can go ahead and take this other one, as well.”

“I have another question for you,” said the patient.

“That’s great; that’s why I’m here,” replied the pharmacist, and the two continued their conversation.

This caring and knowledgeable “pharmacist” is actually third-year PharmD student Megan Wimmer, and her “patient,” Rosalyn, is a standardized patient, who has been helping the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy for 18 years, acting out numerous scenarios to help student pharmacists practice their communication skills.

Co-designed and taught by Betty Chewning, professor in the Social and Administrative Sciences Division at the School of Pharmacy, the Pharmacist Communication course with lab is a weekly class that gives third-year UW–Madison PharmD students (DPH-3) an opportunity to practice their consultation skills in realistic but simulated interactions with standardized patients.

“It’s incredibly helpful to practice on pretend patients,” says Nick Kuroski, DPH-3. “The pressure to do well is still there, because it’s really just one step away from what we’ll be doing as pharmacists, but it’s nice to be able to polish our communication skills before we get out in the real world.”

The course also includes a group project component that helps student pharmacists build their teamwork skills and to be able to work effectively with other pharmacists and health care professionals as part of a team.

Practice consultations with expert feedback

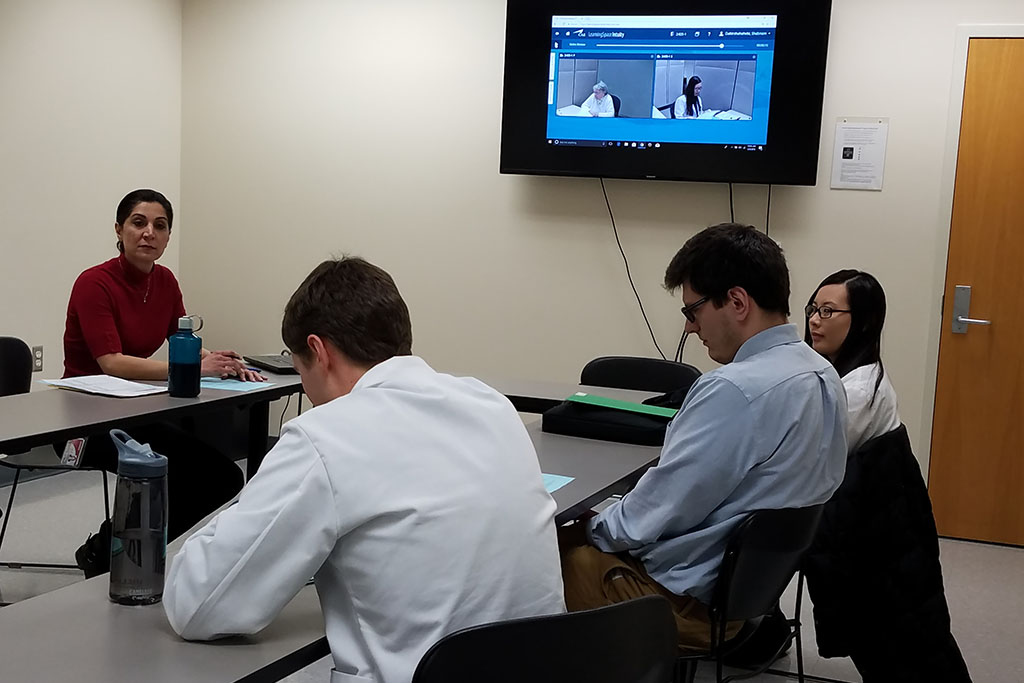

With eight lab sections and 147 students, each student pharmacist is filmed during their patient consultations each week and receives substantial feedback throughout the course from standardized patients, classmates, and instructors (Chewning and experienced pharmacists) about their specific communication skills. Students view the recording before the individual review with an instructor.

“These instructors are committed to the course,” says Chewning. “In addition to our graduate teaching assistants, we have practicing pharmacists, like Charlie Lee from CVS, Shabnam Sahebi from Dean and SSM Health, Roberta Carrier from The Medicine Shoppe, and Yolanda Tolson from St. Vincent’s charitable pharmacy, who are here because they believe so much in helping our students develop these essential communications skills.

“Also, pharmacist Susan Leedham takes care of the course’s complicated infrastructure week after week. We call her our course’s glue. And lecturer Nisa Sangasubana has developed electronic lectures to aid the capstone group project,” says Chewning.

Each week, students work with a standardized patient to practice counseling on a different scenario, which could involve a medication problem or a typical problem that a pharmacist has to deal with in practice, such as an angry patient who is frustrated with their insurance plan.

“One scenario allows students to teach patients to measure their blood pressure using a blood pressure monitor,” says Dale Wilson, the research program manager in the School’s Sonderegger Research Center and the standardized patient coordinator for the past five years, recruiting and scheduling standardized patients for lab sessions, and recording videos of each student’s interaction with a standardized patient that get tagged with each student’s name.

“In another, the standardized patient begins on their cell phone, so a student has to assertively but politely get the patient’s attention, so they can talk to them about their medication,” says Wilson.

One week, the patient has to play the part of someone with a sinus infection who is picking up an antibiotic at the pharmacy, as well as a refill for a medication that they don’t want to admit they forget to take sometimes.

“We try to put in little things that students really might face in practice,” explains Wilson.

“We help the student pharmacists establish rapport with patients using nonverbal and verbal skills, so they’re confident dealing with difficult situations.” –Betty Chewning

“We also give them extremely complicated regimens like a patient with seven medications who was just released from the hospital and doesn’t know how to integrate those meds into their typical day,” adds Chewning. “It’s up to the student pharmacist, in an interactive, supportive way, to help devise a realistic, feasible plan for the patient to be able to take those medications at home that also ensures there are no dangerous drug interactions.”

“So many older adults see specialists who prescribe medications, but nobody helps them integrate those meds into their plan for the day. The pharmacist is the one who can look at that and, in a patient-centered way, help people devise a realistic schedule,” says Chewning.

Intensive experiential learning experiences

On the day of their scheduled lab, PharmD students receive lab introduction from the instructors and work on their group project before their assigned consultation, while Wilson prepares the standardized patients for that day’s scenario. Wilson provides patients with a script, shows a sample video of a consultation with them, and runs through some possible questions the student pharmacists might ask them, before they walk into a room with individual cubicles to meet the students.

Each standardized patient meets with three individual PharmD students in 10-minute increments, after which students write a self-evaluation and the patient provides written feedback, too. Every week, students in each of the eight labs participate in a group review of two or three students who receive feedback from faculty and peers.

“The course increases student confidence by helping them anticipate challenging situations they’re likely to face as pharmacists,” says Chewning. “We’re providing them with very specific training to deal with those anticipated situations, where they get the chance to rehearse how they’re going to handle it, have a chance to get feedback and improve, and come back that next week adapting the skills and refining them more and more each week.”

Students come to the course with extensive drug knowledge. “The advantage of having the course in the last semester before PharmD students begin their clerkships is that their knowledge of drugs can inform the information they offer patients and help them prioritize what they tell and clarify for the patient,” says Chewning.

Chewning says the goal is to give student pharmacists practice with people who are much more like patients than talking with fellow students.

“These patients represent a range of people,” says Chewning. “We help the student pharmacists establish rapport with patients using nonverbal and verbal skills, so they’re confident dealing with difficult situations and also have a partner in the patient, so they can make the consultation efficient, effective, and caring, in the time available.”

“Dr. Chewning really is sensitive to making sure students have a realistic, useful experience, so she always has in mind how to address problems that might come up, trying to teach students about being sensitive and emphasizing empathy,” says Wilson. “I often notice students talking to the patients a bit after they’re done with their consult. They have a really nice connection with some of the patients.”

“We’re one of the few PharmD programs where students have the opportunity to have practicing pharmacists give individualized feedback on their consultations with standardized patients.” –Betty Chewning

The course also incorporates an inclusive mindset to help students learn to communicate with diverse populations. Some standardized patients play the part of a patient with limited English language skills so that each semester, every student has at least one opportunity to work with somebody who speaks little English.

“The experience of communicating with someone who speaks a different language helps you think about how to simplify and makes you think about what you need to communicate,” says Wilson.

“The standardized patients see the value in helping the students be the best possible pharmacists they can be,” adds Chewning.

Unique aspects of the course

Other pharmacy schools offer variations of this course, but two aspects are distinctive about UW–Madison’s Pharmacist Communication course:

- The use of standardized patients and having practicing pharmacists provide real-time feedback.

- Building teamwork and leadership skills through a capstone group project.

“Other courses certainly have some role plays, but the intensity of this is greater because we have standardized patients who provide a more realistic experience than having fellow students act as patients,” says Chewning.

“We’re one of the few PharmD programs where students have the opportunity to have practicing pharmacists give our student pharmacists individualized feedback on their consultations with standardized patients and real-world advice based on their experience as a pharmacist,” adds Chewning.

The course expands beyond patient communication to group communication. PharmD students work in groups to complete an entrepreneurial group project with the pharmacy of their choice. The capstone project takes them from the identification of a need or problem all the way to pilot-testing their solution.

Chewning uses a set of templates from systems design to guide students through the steps of identifying a need or problem, designing a service or project, piloting it, and making recommendations for changes. The majority of the work takes place during class, concluding with a group presentation at the end of the semester, to which pharmacy partners are invited.

“We’ve found that about half of the pharmacy partners continue the projects beyond the class,” says Chewning. “That’s a tribute to our talented students.”

One of the most successful projects actually had a rough start: The group wanted to develop a set of resources to help Spanish-speaking pharmacy patients, but when they conducted a stakeholder survey, they discovered there weren’t many of those patients. The students took a step back, redid their needs assessment, and switched their project to focus on expanding immunizations at their chosen community pharmacy.

Working with the Wisconsin Immunization Registry (WIR)—a unique resource that pharmacies and other health care providers can use to identify needed immunizations and individual patient recommendations based on Centers for Disease Control (CDC) standards—the group developed an efficient way for their community pharmacy partner to access the WIR and ultimately offer immunizations at the pharmacy for these identified patients. Patients snapped up the pharmacists’ offer of immunizations, resulting in dramatically higher immunization rates for flu, shingles, and pneumonia.

The PharmD students published their results in the Journal of the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin, and the CDC saw it, picked it up, and asked the UW–Madison pharmacy students to present a poster at the National Summit on Immunizations.

“Then, this year, I got a phone call from the Gerontological Society of America that they were doing a policy roundtable with lawmakers and their staff in D.C. They wanted to feature the student project, because on top of immunizations being so important, this is the first group that outlined how to work well with the Wisconsin Immunization Registry in a way that had implications as a widespread, feasible approach within the state,” says Chewning.

“It just shows how much impact our PharmD students are making even through their group projects.”

One of the students from the group, Chris Gardipee (PharmD ’16), now has his own hometown pharmacy in Poynette, Wis., and has continued working with the Wisconsin Immunization Registry to further refine a model that WIR can promote to pharmacists.

“I truly believe that pharmacists are the most underused health care resource.”–Betty Chewning

A community supporting student pharmacists

As student pharmacist Megan Wimmer’s “patient” said goodbye, Wimmer cheerfully replied, “I hope you’re feeling better when I see you next time.”

Chewning’s goal is to train all her students to be caring pharmacists like Wimmer.

“I truly believe that pharmacists are the most underused health care resource to people dealing with medications to manage chronic conditions,” says Chewning. “I think we all feel that we’re a community trying to support student pharmacists, so they can help others stay as healthy as they can be and as independent as they can be.”

Learn more about the PharmD program at the School of Pharmacy.