14

March

The School of Pharmacy educates compassionate student pharmacists prepared to provide the best care to every patient

By Katie Gerhards

As sun sets and the new crescent moon emerges, signaling the onset of Ramadan, your family gathers around the dinner table to begin a month-long period of reflection, community, and fasting. Beyond tradition and religious ritual, it’s a spiritual journey and point of connection with your family and loved ones. You want to join the nearly 2 billion people worldwide in observing the Muslim holy month, but, as someone with diabetes, fasting for prolonged periods and eating large meals can endanger your health.

In another town, or just on another street, a family’s car has just broken down. There are doctor appointments to attend, groceries and school supplies to buy, and prescriptions to pick up. How do you use your $30 for the week — to put food on the table, to secure transportation, or to get your prescriptions?

These are the scenarios — faced by millions of Americans each year — that PharmD students at the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy are exploring to better serve their future patients.

“We are committed to training culturally sensitive pharmacists who will care for all patients at the highest level.”

—Mel de Villers

“We’re preparing our students for the breadth of patients they will encounter regardless of their practice location or environment,” says Professor of Pharmacy Practice Casey Gallimore (PharmD ’05, MS ’13), chair of the Curriculum Committee. “Underserved or vulnerable patients don’t come into the pharmacy with labels on. We infuse these themes across the curriculum so students will keep these factors top-of-mind with every patient to improve outcomes and reduce health inequities.”

As part of the School of Pharmacy’s five-year strategic plan to educate, cultivate and innovate — set in 2020 — the School aims to ensure that all PharmD students are prepared to serve medically underserved and vulnerable populations by 2026, such as low-income or rural patients, those with disabilities, and patients facing health disparities.

“We are committed to training culturally sensitive pharmacists who will care for all patients at the highest level,” says Mel de Villiers, School of Pharmacy vice dean and associate dean for academic affairs. “As part of our efforts in pharmacy workforce development and better patient care, the Doctor of Pharmacy curriculum incorporates inclusive content that reflects the needs of today’s patients and standards set by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education.”

Elements of the ambitious strategic goal are woven throughout the four-year curriculum, and pharmacy students get tangible experience through a poverty simulation, a communications lab focused on counseling patients through religious fasting, and experiential rotations in medically underserved areas.

“We want our PharmD students to be ready to improve care in every situation,” says Lisa Imhoff, associate dean for diversity and inclusion initiatives. “Healthcare as a need is universal, but the way it plays out in different populations is not.”

Understanding the pressures of poverty

There are 37.9 million Americans living in poverty, accounting for 11.5 percent of the population. For pharmacists, that means one in 10 patients. To help PharmD students understand the pressures these patients face, the students undergo a poverty simulation, organized by Kate Rotzenberg (PharmD ’07), associate teaching professor, and Olayinka Shiyanbola, associate professor of social and administrative sciences.

“We want to help our students recognize what people in poverty are going through and to help build empathy and understanding,” says Rotzenberg.

The simulation takes place as part of the Social and Behavioral Aspects of Pharmacy Practice course, which gives first-year pharmacy students insights into unique non-medical patient factors that influence their health outcomes.

“Through this course, the students get a lot of content around health equity, health care disparities, talking to our elderly, and providing care for people from different racial and ethnic groups,” says Shiyanbola. “The whole idea leading to the poverty simulation is about social justice and health, which helps to build the foundation that this is another unique marginalized population — those who are socially and economically disadvantaged.”

Classroom learning is key to help PharmD students learn how to screen patients, what resources to provide for patients who are struggling to afford medications, and to complete “cause of the cause” analyses to understand the reasons for certain patient behaviors that may be negatively affecting their health — reasons that are sometimes outside their control. But the simulation gives students the opportunity to put themselves in these patients’ shoes.

“The simulation facilitated an understanding of some of the stress that many patients face on a daily basis,” wrote a PharmD student on a course evaluation. “I think that it’s important to recognize that our patient’s life circumstances have more influence on their behavior than their disposition. Understanding the demands of life on a low-income person helps us to be empathetic in our care and proactive in designing treatment to fit in with our patient’s lives.”

In the simulation, pharmacy students are randomly assigned into family groups, each of which has a backstory with challenges they must overcome. The experience is structured as four 15-minute rounds, each representing a week spent in poverty. During that week, they attempt to achieve the goals the family has set for themselves. For example, if the family is facing eviction, the goal may be to find housing. Or if their child’s school is closed, then they need to find childcare so they don’t miss work and lose their job. Or maybe they don’t have enough money to cover their groceries and need assistance with food. Students are immersed in the simulated community to create empathy for patients.

“We debrief on the experience they had and have them write a reflection on that experience where our goals are to help them recognize the individuality of the patients they’re seeing, the challenge of meeting healthcare needs with limited economic resources, and identifying pharmacists’ role in caring for them,” says Rotzenberg.

This hands-on learning experience will be valuable across pharmacy practice settings.

“These activities allow student pharmacists to think about public health as well, because they are public health practitioners who need to think beyond the pharmacy,” says Shiyanbola. “If you look at the research coming out of the world of social determinants of health, it’s not just community pharmacies engaging with this anymore — anybody working in the health system is going to find themselves facing it, and our students will be prepared.”

Counseling across cultures

Social and Administrative Sciences Professor Betty Chewning couldn’t shake the feeling that they could do a better job preparing students to navigate cultural differences. With former alum Mohamed Amin (PhD ’13) and Health Services Research in Pharmacy graduate student teaching assistants Bonyan Qudah, Marwa Rawy, and Arveen Kaur, Chewning and the team came up with the idea to teach PharmD students how to guide Muslims with diabetes through Ramadan fasting. It’s a clear, concrete example that fills a common knowledge gap in care.

“I don’t think most pharmacists are prepared for it — I don’t think most physicians are, either,” says Chewning. “We want to introduce student pharmacists to cultural differences that have to do with religious fasting — regardless of whether you have diabetes or any other serious illness. We want students to develop the skills to negotiate a very complicated situation in partnership with the patient to improve their safety.”

Since 2005, Chewning has taught the School of Pharmacy’s Communications Lab course, which gives third-year PharmD students realistic experience with patient consultations. The course typically has a full week of three-hour labs focused on a particular scenario, where pharmacy students roleplay consultations with standardized patients — paid actors simulating real patients — to help these scenarios come to life. The consultations are recorded so students can evaluate themselves and others.

The fasting-focused lab is entering its third year in-person. It starts with a panel discussion featuring Muslim and Jewish community members, who then stand in as standardized patients for students’ consultations. Including Jewish fasting helps to further expand students’ perspectives and how to apply the lesson to various cultures.

One of the hurdles is helping pharmacy students, who are carrying huge amounts of medication information and expertise, learn how to hold back on that information and instead turn the consultation into an interview to identify why the patient would consider some strategies to make fasting as safe as possible.

PharmD students work with the patients to discuss medication dosing, avoiding major changes in blood sugar, modifying the amount of food being eaten, negotiating blood sugar monitoring, and having a backup plan.

“I really, really appreciated this experience,” wrote one PharmD student in the course evaluation. “As someone who is very unfamiliar with Ramadan yet is intentionally passionate about the principles of inclusivity, I found great value in having open dialogue in a safe space with people that practice and celebrate these religious holidays. I’m grateful for the experience and would highly encourage the program to continue providing students these learning opportunities — it is what separates us from other pharmacy schools and pharmacists!”

To further enhance students’ skills with vulnerable populations, the Communications Lab also has sessions that give them experience with limited English proficiency patients where pharmacy students also learn how to work with interpreters in a three-way conversation.

“You can talk at somebody all you want, but if they’re not understanding, it’s worthless,” says Chewning. “Improving these interactions to positively impact patients of all backgrounds is at the heart of what we’re trying to do.”

Classroom to pharmacy practice

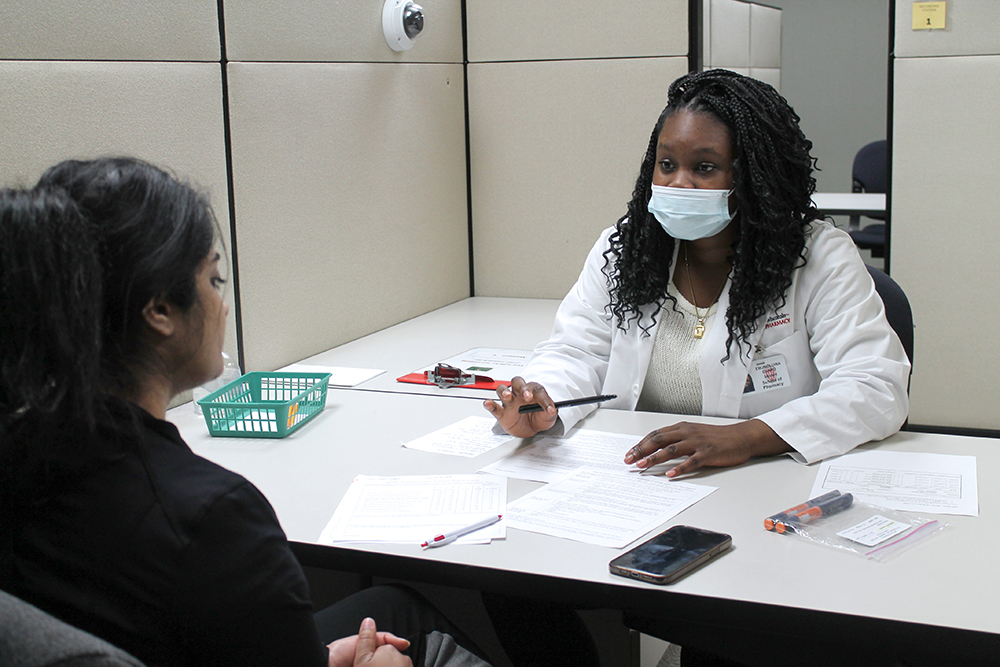

Student pharmacists pair their learning in the classroom with clinical training through experiential rotations beginning in their first year of the PharmD program. By watching pharmacists work in different practice settings with a range of patients, PharmD students gain a greater understanding of their role as the most accessible health care provider.

To ensure PharmD students are prepared to serve medically underserved populations, all PharmD students complete an Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experience (IPPE) clinical rotation with medically underserved patients.

“Our PharmD students will care for a breadth of patient populations wherever they decide to practice,” says Assistant Dean for Experiential Education Mara Kieser (BS ’81, MS ’84). “To know our students are prepared, we built meaningful interactions with medically underserved and vulnerable populations into the experiential curriculum so students can see firsthand what challenges these patients face and how pharmacists can help address them, bringing their classroom work into practice.”

Associate Professor of Pharmacy Practice Amanda Margolis (PharmD ’09, MS ’17) spearheaded a group reviewing all of the sites hosting PharmD students for IPPEs and Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences (APPEs) to get a greater understanding of the patient populations with whom students interact.

In order to survey preceptors about their patients, the team first needed to define medically underserved patients.

“We generally adopted the Health and Human Services (HHS) definition, with a few tweaks,” says Margolis. The HHS definition includes minority populations and those that have experienced disparities, including rural patients, individuals with disabilities, Medicaid-eligible patients who are not enrolled in coverage, refugees, and more. Importantly, these individuals receive fewer healthcare services, encounter barriers to primary care services, and can be unfamiliar with the healthcare system.

“The idea is that if one in five patients is from one of these categories, we know that our students will interact with them during their rotation,” says Margolis.

The initial evaluations showed that students have been meeting the goal of completing an experiential rotation with medically underserved patients for several years, so the team then turned to the real intention of the strategic plan initiative: to have students learn how to improve their care.

“Our PharmD students will encounter a breadth of patient populations wherever they decide to practice.”

—Mara Kieser

After rotations, PharmD students complete reflections that give them the chance to process the experience, review what they learned, and think about new or unexpected situations and how they were resolved. The students’ reflections also serve to improve the curriculum, giving faculty insight on whether the rotations need to be preceded or followed by certain topics to help students connect their classroom learning with their clinical training experiences.

“With the addition of reflections, discussions, and other activities in each year of the program, students are gaining patient experiences and are also being prepared to better serve medically underserved populations,” says Associate Professor of Pharmacy Practice Andrea Porter (PharmD ’06).

Patient-centered care

“I will promote inclusion, embrace diversity, and advocate for justice to advance health equity.” So reads the Oath of a Pharmacist, created by the American Pharmacists Association and American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) and taken by each graduating pharmacy student across the nation.

As one of the top pharmacy schools in the country, the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy aims to ensure that its PharmD students are prepared to meet each promise within the Oath, including the commitment to health equity.

According to the most recent AACP Graduating Students Survey, 95 percent of UW–Madison PharmD students indicated that they could identify healthcare disparities in 2022, up 10 percentage points from 2019. Significant strides were made on AACP’s expectations of recognizing and addressing disparities in healthcare access and delivery where 96 percent of UW–Madison students agreed they could, compared to 84 percent in 2019. And 99 percent of PharmD students said they had direct interactions with diverse patient populations during the School’s experiential education program.

“The preparation we receive to help underserved patients is so important because, regardless of where we practice, we want to make sure we are providing inclusion-forward care,” says fourth-year PharmD student Maria Hill. “It’s important to think about the issues impacting health equity and develop ideas on how to overcome them before we get into the workplace. In this way, the UW has done a great job preparing me for my future patients.”