3

December

Alum Mohamed Amin empowers clinicians and patients with culturally relevant care

By Stuti Bhardwaj

One of the largest annual religious observances for the world’s nearly 2 billion Muslims is Ramadan, which lasts for an entire month and means that participants refrain from eating or drinking between sunrise and sunset while focusing on prayer and reflection.

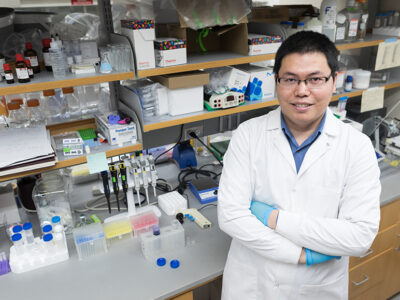

As a pharmacist native to Alexandria, Egypt — where more than 90 percent of citizens are Muslim — Mohamed Amin (PhD ’13) could clearly see an opportunity for pharmacists to guide patients through Ramadan safely, with respect for both their religious obligations and their health.

“Should patients choose to fast, we need to make sure they do so in the safest way possible,” says Amin. Although some medications and diseases states, such as diabetes, make it dangerous for some patients to fast, pharmacist support and supervision can make it safer by adjusting medication regimens and working with patients to educate them on when the fast must be broken.

“Even if it’s not recommended for patients with certain risks to fast, I would still want them to do so under medical supervision if they choose to fast,” he says.

As a graduate student in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Health Services Research in Pharmacy program (then called Social and Administrative Sciences in Pharmacy), Amin delved into research about how pharmacists can best support Muslims throughout the month of Ramadan, leading to nearly a dozen publications.

“Given 2.15 million Muslim adults in the US, the need for Wisconsin pharmacists’ help is especially important with a growing number of Muslim refugee groups settling in Wisconsin.”

—Betty Chewning

“Even in countries with Muslim majorities, pharmacists and other clinicians have struggled with advising patients on how to fast during Ramadan,” he says, and he wants to change that.

As part of ongoing collaboration with the School of Pharmacy and Professor Betty Chewning, his former research mentor, Amin chose the School to debut a pilot of a new tool designed to teach clinicians how to counsel patients on religious fasting.

“Dr. Mohamed Amin’s important research is helping to sensitize practicing pharmacists internationally and student pharmacists here in the School of Pharmacy about the importance of considering Muslim rituals,” says Chewning. “Given 2.15 million Muslim adults in the US, the need for Wisconsin pharmacists’ help is especially important with a growing number of Muslim refugee groups settling in Wisconsin.”

Pharmacist involvement in Ramadan

What originally attracted Amin to pharmacy was the accessibility of pharmacists as health professionals.

“For you to see a physician there are usually many hurdles, especially for patients who do not have many resources, community pharmacy in particular, represents an accessible way of reaching and serving these patients,” he says.

While poring through research to learn how to best support his community as a pharmacist, he became familiar with the work of School of Pharmacy faculty, such as Chewning and Professor Emerita Bonnie Svarstad, which is what led him to apply.

After graduating from the School of Pharmacy, he returned to the Middle East and took a faculty position with the Beirut Arab University School of Pharmacy, where he worked with the dean and fellow faculty members there to modernize the curriculum and pursue Canadian accreditation of the professional pharmacy program.

“A lot of times the pharmacy curriculum in developing countries has a large proportion of pharmaceutical science classes, but not enough social pharmacy and pharmacotherapy classes,” he says. “It was a great opportunity to renovate a pharmacy program so that graduates are empowered with skills that allow them to provide the best service for their communities.”

He returned to the U.S. to spend a few years as a faculty member at Manchester University in Indiana, and then again returned to Beirut Arab University. But before returning to Beirut, he created a tool called RAMCOM, short for Ramadan Communication, to help health professionals to better understand how to serve their patients who consider religious fasting. The tool, which was co-created with Ahmed Abdelmageed, at the University of Saint Joseph, and Marwa Farhat, at CVS, was designed to guide pharmacists and other clinicians through patient conversations about Ramadan.

Amin is concerned that doctors and pharmacists are often quick to dismiss patients’ desires to fast, leaving patients to enter the fast without the care or support of a health professional — which, at times, can be extremely dangerous. With RAMCOM, clinicians will be more equipped to offer support.

“I look for concordance here,” he says. “I want shared decision-making with the patient, which I learned from Professor Chewning.”

Amin hopes that his research can be used to help a diverse array of patients from different cultural backgrounds. One of his friends, who is a doctor in the US, is using RAMCOM to prepare health professionals who are working with Afghan refugees, a majority of whom are Muslim and observe Ramadan.

“It’s really encouraging to see our work being used to help others,” he says.

A tool for student pharmacists

While at Manchester University, Amin had the idea to expand his research to include a breadth of religious and cultural fasts, beyond Ramadan. The expansion was spurred by a student who mentioned that he would soon be observing Shravan, a Hindu holy month that incorporates several types of fasts.

“There is a significant overlap into the needs of these patients — and even the religious value of fasting — and how a health professional or student would prepare for addressing those needs,” he explains. “I want students to understand how to give patients culturally appropriate responses and be more comfortable in working with them.”

To prepare future practitioners to provide quality, culturally relevant care to their patients, Amin struck a collaboration with Chewning and Bonyan Qudah, Arveen Kaur, and Marwa Rawy, all of whom are Health Services Research in Pharmacy graduate students at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy. The team developed an assignment for PharmD students that debuted in the School of Pharmacy’s Communication Lab.

“This class is a benchmark for clinician-patient communication classes for pharmacy schools across the country,” Amin says.

The assignment is a simulation of different scenarios where patients with diabetes come to the pharmacy with needs for religious fasting, focused on Ramadan, Shravan, and Yom Kippur, a Jewish daylong fast.

Presented with the scenarios, clinician and patient video versions of RAMCOM, and other published materials, student pharmacists are asked to come up with culturally appropriate responses to meet patients’ needs. Instead of telling patients that fasting is unsafe and cautioning against it, PharmD students learn how to offer their support and expertise to get patients with diabetes to make an informed decision on fasting and to make it as safe as it can be if patients choose to fast.

“Daily fasting for the month of Ramadan needs to be anticipated and planned for so that diet and medication administration can be safely integrated during that month,” says Chewning. “Third-year PharmD students completed a successful exercise in the Pharmacist Communication course designed to raise students’ knowledge and skill to respectfully help Muslims and other groups plan how to navigate their care and rituals.”

More than 70 percent of PharmD students found the assignment useful or extremely useful in increasing their confidence working with patients who participate in religious fasting, and the results were published in Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. Amin says the School’s students were eager to learn more about these diverse religious holidays and the fasting that goes along with it.

“This made me pleasantly surprised,” he says. “It says a lot about Pharmacy Badgers: They are not just good students but also good people who want to help patients across denominations including patients who might be different than them.”

Empowering patients

Amin continues to remain in touch with many of his colleagues from the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy, often bouncing his research ideas off them. He participates in the Alumni Link program at the School of Pharmacy, which matches recent graduates with alumni who have had longer to establish their careers and build professional networks, like Amin.

His connection with Chewning and the School’s Health Services Research in Pharmacy graduate students inspire him to keep expanding his ideas for improving global health.

“Professor Chewning really takes her profession seriously, and not just within the US border but internationally,” says Amin. “She truly embodies the Wisconsin Idea.”

“I want our health systems, and systems in general, to pay attention to the needs of those who are most vulnerable and those who do not represent the majority.”

—Mohamed Amin

Amin, who is now affiliated with Beirut Arab University in Lebanon and AlAlamein International University in Egypt, currently carries out research that spans across a large span of clinician-patient communication and empowerment. He hopes to ensure that pharmacists and pharmacies can be healthcare access points for patients from diverse backgrounds and needs — the reason he got pulled into pharmacy to begin with.

In addition to religious fasting, his research with his graduate students at Beirut Arab University addresses other issues of importance to practicing pharmacists, including pharmacogenomics and deprescribing. His newest research is exploring how pharmacies can be support systems for migrant domestic workers in the Middle East, as well as how pharmacists can deliver information about contraceptive choices to women in a way that empowers them.

“I want our health systems, and systems in general, to pay attention to the needs of those who are most vulnerable and those who do not represent the majority,” he says.