Collaborative is a system redesign initiative to improve antibiotic prescribing in skilled nursing facilities. The study aims to improve antibiotic prescribing in nursing homes by facilitating \ antibiotic decision-making. Improvements target two decisions: the initial antibiotic decision before an antibiotic is prescribed, and a subsequent review of the antibiotic order after the antibiotic is prescribed. The intervention is being implemented using a Quality Improvement Collaborative (QIC) process, a facilitated implementation that includes coaching facilities both individually and in groups.

Antibiotic resistance is one of the three greatest threats to human health according to the World Health Organization [1]. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile are responsible for 2.3 million infections and 37,00 deaths in the U.S. every year [2]. Up to 40% of nursing home (NH) residents are colonized with antibiotic-resistant bacteria [3] and NHs play a critical role in the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance and C. difficile in the communities they serve [4-6]. Antibiotics, the major driver of antibiotic resistance and C. difficile, are prescribed to 65% of individuals who reside in a NH for ≥ 6 months [7] and up to 75% of antibiotic use in NHs is inappropriate [8]. NH antibiotic stewardship, a generic term used to describe procedures for improving the use of antibiotics, has been designated by the CDC as a critical need [9]. The impact of antibiotic stewardship interventions on prescribing behaviors in NHs has been mixed [10-13]. While multi-component educational interventions appear to have a modest impact on prescribing behaviors in NHs [11,14,15], it is unclear if outcomes observed in these studies are mediated by interventional or observer (Hawthorn) effects. Consequently, there is a desperate need to not only evaluate stewardship interventions for their impact on prescribing behaviors but to also determine the mechanisms by which they mediate these changes. Absent this approach, our ability to generalize results from quasi- experimental studies to other settings will remain limited and large-scale, sustainable improvements in antibiotic use in NHs will not be possible.

Our long-term goal is to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use in NHs. We have developed the Optimizing Antibiotic Stewardship In Skilled Nursing Facilities (OASIS) intervention based on the literature and our strong preliminary data. This intervention seeks to improve antibiotic prescribing in NHs through five distinct components: 1) education of NH staff and prescribing providers; 2) tools to support resident assessment and staff/provider decision-making; 3) tools to support inter-professional communication; 4) post-prescribing review of antibiotic necessity/de-escalation; and 5) tools to support facility quality improvement. The objectives of this proposal, the next step in pursuit of our long-term goal, is to demonstrate the efficacy of the OASIS intervention in a selected sample of Wisconsin and Pennsylvania NHs, assess how OASIS mediates change in process and outcomes in study NHs, and develop a resource to disseminate the intervention to other NHs.

Specific Aim 1: Tailor the OASIS antibiotic stewardship intervention for optimal implementation in study NHs.

Specific Aim 2: Assess impact of the OASIS intervention on antibiotic use in NHs.

Specific Aim 3: Develop a toolkit to support further dissemination of the OASIS intervention.

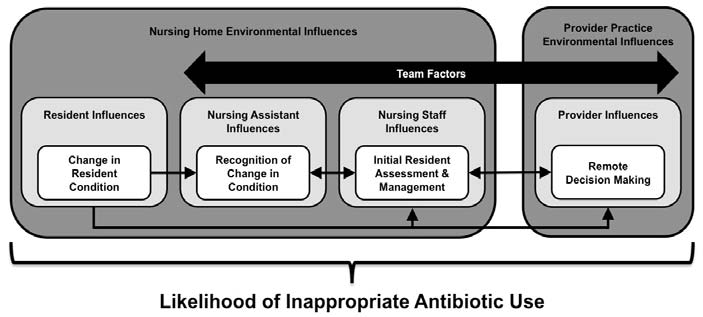

The antibiotic decision-making process in NHs is influenced by interactions (large black bidirectional arrow) between a number of components: 1) events/processes (white boxes); 2) characteristics and decisions of individuals involved in those events/processes (light grey boxes); and 3) the environment in which they occur (dark grey boxes).