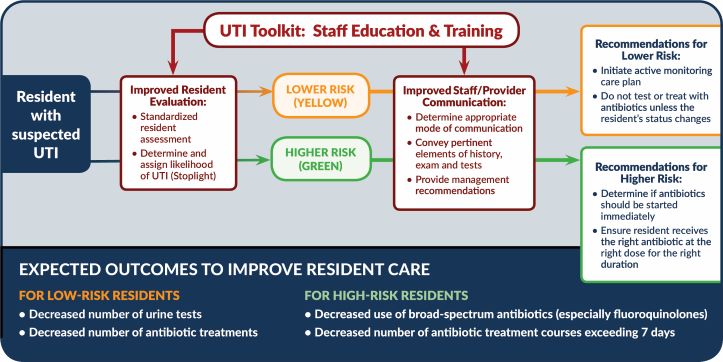

This project will evaluate the impact of the Wisconsin UTI Improvement Toolkit on antibiotic prescribing for UTI and assess the influence of external facilitation on adoption and effects of the toolkit in Wisconsin NHs. The primary study objectives are to assess the overall impact on antibiotic utilization and determine the extent to which effects vary by the implementation approach employed. We will achieve these two objectives through the following specific aims: 1) Evaluate the impact of the Wisconsin UTI Improvement Toolkit on antibiotic prescribing for UTI in Wisconsin NHs and 2) Assess the influence of external facilitation on adoption and effects of the Wisconsin UTI Improvement Toolkit in Wisconsin NHs.

To access the toolkit please visit Wisconsin Long-Term Care Urinary Tract Infection Toolkit.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Background

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics is a major public health problem in Wisconsin nursing homes (NHs) [1] that adversely impacts resident and community health through adverse drug reactions [2], Clostridium difficile infections [3] as well as development and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria [4,5].

Treatment of suspected urinary tract infection (UTI) accounts for nearly half of the antibiotic use in Wisconsin NHs [1]. Less than half of the antibiotics prescribed for UTI in Wisconsin NHs are not justified [6] and improving the management of UTI in NHs has been identified as a major priority by experts in the field [7-9].

We along with our community partners have developed a toolkit of evidence-based practices for improving the management of UTIs in Wisconsin NHs (hereafter referred to as the Wisconsin UTI Improvement Toolkit). While use of the practices incorporated in the Wisconsin UTI Improvement Toolkit has resulted in notable improvements in the quality of antibiotic prescribing for the treatment of UTI in a number of studies [10-12], more limited effects have been observed in other studies despite employing similar improvement strategies [13-15]. Heterogeneity of effects across different settings is a problem commonly encountered with healthcare behavioral interventions and may arise due to characteristics of the intervention, the setting into which it is being introduced and the method of implementing the intervention in that setting [16]. There are a number of challenges to improving quality in NHs, including lack of improvement expertise [17] and high levels of staff turnover [18] to name a few. It is unrealistic to expect that these structural barriers will abate anytime soon. Consequently, it is critically important to identify effective strategies to overcome them if meaningful improvements in the quality of antibiotic prescribing in NHs is to be achieved.

Aims

Specific Aim 1: Evaluate the impact of the Wisconsin UTI Improvement Toolkit on antibiotic prescribing for UTI in Wisconsin NHs.

Specific Aim 2: Assess the influence of external facilitation on adoption and effects of the Wisconsin UTI Improvement Toolkit in Wisconsin NHs.

Logic Model

The behavioral objectives of the toolkit are to (1) improve nursing staff assessment of residents experiencing a change in condition potentially attributable to UTI; (2) improve the quality of inter-professional communication when a diagnosis of UTI is being considered; (3) ensure that nursing staff and clinicians ascertain the likelihood of UTI (low vs high probability); (4) defer urine testing and antibiotic therapy when the probability of UTI is low; and (5) prescribe antibiotics appropriately (choice of agent and treatment duration) when the probability of UTI is high.

References

- Crnich C, Dreis M, Hess T, Drinka P, Zimmerman DR. Patterns and discrepancies between different metrics of antibiotic use in nursing homes (Oral Abstract Presentation #1789). San Diego, CA: 2012.

- Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, et al. Risk factors for adverse drug events among nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161:1629–1634.

- Hunter JC, Mu Y, Dumyati GK, et al. Burden of Nursing Home-Onset Clostridium difficile Infection in the United States: Estimates of Incidence and Patient Outcomes. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3:ofv196.

- Lee BY, Song Y, Bartsch SM, et al. Long-term care facilities: important participants of the acute care facility social network? PLoS ONE 2011; 6:e29342.

- Mody L, Crnich C. Effects of Excessive Antibiotic Use in Nursing Homes. JAMA Internal Medicine 2015; 175:1339–1341.

- Crnich CJ, Miller J, Bahrainian M, Adibhatla S. Comparison of explicit criteria for determining appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing in nursing homes. SHEA Spring Conference. 2015;

- Crnich CJ, Jump R, Trautner B, Sloane PD, Mody L. Optimizing Antibiotic Stewardship in Nursing Homes: A Narrative Review and Recommendations for Improvement. Drugs and Aging 2015; 32:699–716.

- Nace DA, Drinka PJ, Crnich CJ. Clinical uncertainties in the approach to long term care residents with possible urinary tract infection. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014; 15:133–139.

- van Buul LW, Veenhuizen RB, Achterberg WP, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in Dutch nursing homes: how appropriate is it? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015; 16:229–237.

- Zabarsky TF, Sethi AK, Donskey CJ. Sustained reduction in inappropriate treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in a long-term care facility through an educational intervention. Am J Infect Control 2008; 36:476–480.

- Frentzel E, Moudouni DKM, Garfinkel S, Phillips C, Zhao H, Fuchs S. Standardizing Antibiotic Use in Long-Term Care Settings (SAUL Study): Final Report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Accelerating (AHRQ) ACTION Contract No. 290-2006-000-191, Task Order No. 8. American Institutes for Research, Texas A&M University School of Rural Public Health, and TMF Health Quality Institute, 2013.

- Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Approach for Urinary Catheter-Associated Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. JAMA Internal Medicine 2015; 175:1120–1127.

- Loeb M, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, et al. Effect of a multifaceted intervention on number of antimicrobial prescriptions for suspected urinary tract infections in residents of nursing homes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005; 331:669.

- Monette J, Miller M, Monette M, et al. Effect of an Educational Intervention on Optimizing Antibiotic Prescribing in Long-Term Care Facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:1231–1235.

- Pettersson E, Vernby A, Mölstad S, Lundborg CS. Can a multifaceted educational intervention targeting both nurses and physicians change the prescribing of antibiotics to nursing home residents? A cluster randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66:2659–2666.

- Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci 2008; 3:1.

- Rantz MJ, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Flesner M, et al. Challenges of using quality improvement methods in nursing homes that “need improvement”. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012; 13:732–738.

- Castle NG, Engberg J. Staff turnover and quality of care in nursing homes. Med Care 2005; 43:616–626.

Grant information

This project was supported by the Wisconsin Partnership Program (WPP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the WPP.