Through the Opioid Task Force, Healing Network, and Pharmacy Examining Board, pharmacist alum John Weitekamp works to protect patients

By Katie Ginder-Vogel

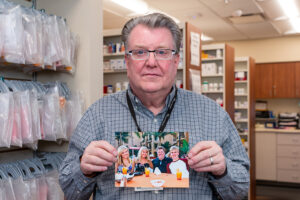

In 2015, John Weitekamp’s life and career took an unexpected turn when his son Ben committed suicide following a struggle with heroin addiction that led to an overdose.

“I decided I could let that ruin everything or get back on the horse and do something about it,” says Weitekamp (BS ’82). “I didn’t want anyone else to go through what my family and I did.”

That same year, Weitekamp volunteered as the pharmacist member of the Wisconsin Task Force on Opioid Abuse, under then-Governor Scott Walker, serving for three years until the task force was absorbed into the State Department of Health Services State Council on Alcohol and Drug Abuse.

“Love the person, hate the addiction.”

—John Weitekamp

Weitekamp’s devotion to ending opioid misuse has led him to participate in several boards and groups at the state and local levels, committed to informing and supporting community members as they or a loved one break free of opioid dependency.

“Love the person, hate the addiction,” says Weitekamp. “The amazing thing about substance misuse disorder is that even as a trained health care provider, signs of drug misuse are easily missed especially when it involves loved ones.”

Opioid advocacy

Pharmacy runs in Weitekamp’s family. He has practiced pharmacy in West Allis, Wis., for 34 years, which became an Aurora Pharmacy in 1998. Here, he keeps a close eye on opioid prescriptions and focuses on patient education and suggesting alternative pain relief options.

If he notices a patient is being prescribed increasing amounts of opioids, which can increase the risk of accidental overdose or an opioid dependency, he lets his patients know his concerns. He will tell his patients, “I see you must be having increased pain because the doctor has been increasing your opioid amounts. Let me tell you about some alternative treatments you can try.”

He refers patients to pain specialists and clinics, where they can receive steroid injections, massage therapy, and other non-addictive pain relief treatments.

“I want them to understand that I truly care about them and that their pain relief matters,” he says. “If even one patient tells me they reduced or stopped taking opioids because of suggestions made by me, that represents a lifetime of success.”

In addition to his own pharmacy practice, Weitekamp has also been involved in the Aurora Pharmacy Practice Council Opioid Subgroup.

“We developed best practices of what pharmacists should consider when filling an opioid prescription,” says Weitekamp, who served as Practice Council chair for three years. “Whenever a pharmacist gets an opioid prescription, they should check the Wisconsin Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) to look for misuse, then calculate the morphine milligram equivalent dose of the prescription and gather a diagnosis to make sure the therapy is appropriate.”

Morphine milligram equivalent doses help providers and pharmacists equate the potency of various opioids against the potency of morphine. This is used as a standard value to monitor and avoid the potential for an overdose. If the patient fits the Centers for Disease Control criteria for a naloxone prescription, the pharmacist has a collaborative practice agreement to dispense the medication when necessary.

Weitekamp has been a member of the Wisconsin Pharmacy Examining Board and the Wisconsin Controlled Substances Board since July of 2018. He has served as the Pharmacy Examining Board chairperson since January 2021. The Controlled Substance Board oversees the PDMP, which tracks data on opioid and stimulant prescriptions. PDMP data shows that opioid prescriptions in Wisconsin declined by about 30 percent between 2016 and 2019.

“One thing we realized is that you can’t legislate [substance misuse] away and you can’t arrest it away; this is a disease that you have to treat.”

—John Weitekamp

“Through the PDMP, we can see trends, like opioid prescriptions going down, but stimulant prescriptions going up,” says Weitekamp. “Or we have seen high amounts of opioid prescriptions in a certain area, but not as much in an area 100 miles away. If any trend is tracked to a certain provider, the Controlled Substance Board can refer them to the appropriate examining board whether they are a pharmacist, pharmacy, physician, dentist, nurse or other health care practitioner.”

Through his work on the Wisconsin Task Force on Opioid Abuse, he worked with the Pew Charitable Trust, who provided 18 recommendations for the state and treatment facilities, including allowing sites that provide health care to serve as opioid treatment facilities and creating a referral tool for providers.

The task force also visited sites around the state to see the regional effect of opioids.

“We went up to Minocqua to see how opioid misuse had affected the Native population and what we could do there,” Weitekamp says. “One thing we realized is that you can’t legislate the problem away and you can’t arrest it away; this is a disease that you have to treat. Realistically, you have three options: incarceration, death, or treatment, and the obvious best choice is treatment.”

Weitekamp is the treasurer of the Greater Milwaukee Lutheran Synod Task Force on Opioid and Substance Use Disorders, now known as The Healing Network. The organization was created out of a recognition that families of opioid users were going to their pastors to seek help, but religious leaders weren’t necessarily trained to address that challenge. Now, the Healing Network collaborates with congregations in greater Milwaukee to train people and establish ministries on substance use and how they can help.

“I’ve been working with amazing people to accomplish great things,” says Weitekamp.

A family of pharmacy leaders

Back when Weitekamp was a pharmacy intern, he saw his preceptor’s pharmacy license on the wall, emblazoned with the signatures of everyone on the Pharmacy Examining Board.

“My grandpa’s signature was on there,” recalls Weitekamp. “From that moment on, I thought it would be cool to be on that board to make changes to the profession and get to sign licenses, too.”

That grandfather is pharmacist Max N. Lemberger, who was not only a member of the Wisconsin Pharmacy Examining Board but also one of the founding fathers of the American College of Apothecaries, an international professional organization for independent community pharmacists.

His two sons, Max A. Lemberger, Jr. (BS ’44, MS ‘71), and August P. Lemberger (BS ’48, PhD ’52), were also notable pharmacists who both won Alumnus of the Year and Citation of Merit awards from the School of Pharmacy. Max Jr. became a pharmacy professor at UW–Madison and then at University of Florida, and August Lemberger served as dean of the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy from 1980 — Weitekamp’s second year in pharmacy school — until 1991.

When a position opened on the Wisconsin Pharmacy Examining Board (PEB), Weitekamp applied and was appointed to the board in 2018. His first four-year term will conclude July 2022.

In addition to signing pharmacy licenses, he and his PEB colleagues are responsible for reading cases, rules, and statutes and understanding their potential impact on pharmacy practice in the state. When state legislators create certain statutes, the PEB develops specific rules for how the statutes will play out in the profession. For example, in 2020 they wrote PEB Chapter Phar 7 on Pharmacy Practice, including guidance on automated and remote dispensing, thinking ahead to the possibilities of how it might work, with both current and future technology.

“If you could have a pharmacy vending machine in a gas station, you would still need to make sure the public is protected, the patient could get consultations, and that the various facets and safeguards of pharmacy would still take place,” says Weitekamp.

In 2020, the PEB also created certain variances for COVID-19, to make sure pharmacies and pharmacists had the tools they needed to serve their patients during the pandemic.

“We wrote a variance to temporarily allow holders of wholesale distribution licenses to distribute prescription drugs from facilities that are not licensed in Wisconsin, but are licensed in other states, should the licensee’s Wisconsin facilities shut down. The purpose of this request was to prevent supply chain disruptions during the COVID-19 emergency,” says Weitekamp. “We also wrote a variance for licensure, so pharmacists from other states could be temporarily licensed here to practice, when there was a severe shortage of pharmacists.”

Weitekamp’s next step is to transition from a supervisor to a float pharmacist.

“I‘ve been working in retail pharmacy for 40 years, and I think it’s time to take a little step back and do some traveling,” he says. “But I don’t want to retire because I love what I’m doing.”