The School of Pharmacy’s new Mental Health Skills Lab is preparing pharmacists to recognize red flags for suicide, ask questions, and save lives

By Archer Parquette

While on a clinical rotation at the Tomah VA Medical Center, Alyssa Schirmers (PharmD ’24) and Maria Hill (PharmD ’24), two students from the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy, came to a jarring realization. They were prepared to respond to patient concerns about medication, to manage prescriptions and documentation, and to gain more experience working with healthcare teams. But one thing caught them off guard: patients were expressing suicidal thoughts.

When Hill’s preceptor asked a patient the hospital’s standardized depression-screening question, “Do you ever wish you could go to sleep and never wake up?” — the patient said “yes.”

“It took me aback,” Hill said. “After that interaction, my preceptor asked me what I would have done if it was me. I said, ‘Honestly, I have no idea.’ I felt unprepared.”

Schirmers had a similar experience while performing a routine diabetes follow-up, when one of her patients who appeared extremely depressed told her he’d recently lost a family member.

Neither student pharmacist knew what to do. Ask more questions? Refer them to someone? Where does a pharmacist fit into mental health care? How do you begin to carefully, compassionately respond to a patient who might not want to live anymore?

The night after Hill’s alarming interaction, they both talked about their experiences and decided to email Jessica Bergsbaken, an assistant teaching professor at the School of Pharmacy, to suggest building suicide prevention skills into the curriculum.

The email inspired Bergsbaken — and led to a new, award-winning learning experience.

To equip student pharmacists for these potentially life-altering conversations, the School of Pharmacy debuted a Mental Health Skills Lab with a Suicide Prevention Discussion and Application last year. It was so successful in its first two years that the new lab won the School of Pharmacy’s inaugural 2025 Inspire Teaching Award for Instructional Excellence in the professional education category.

“These skills are vital because suicide is a common occurrence in this country and worldwide,” says Professor of Pharmacy Casey Gallimore (PharmD ’05, MS ’13), who co-developed the lab.

Building a framework

After Schirmers and Hill shared their uncertainty surrounding suicide prevention, Bergsbaken worked with Gallimore, who also serves as a pharmacist at Tellurian Behavioral Health to review what students already learn about mental health.

“I checked to see if suicide prevention was being covered in other places in the curriculum and realized there was a gap,” Bergsbaken says.

“But when you repeat those uncomfortable questions — like ‘Do you ever want to go to sleep and not want to wake up?’ — you get more comfortable and more confident asking. That’s really what I hoped would come out of this lab.”

–Alyssa Schirmers

Gallimore teaches mental health content in the School’s Pharmacotherapy I course, and Bergsbaken teaches in the Integrated Pharmacotherapy Skills Lab, a series of four hands-on courses that teach future pharmacists best practices for scenarios they will likely encounter in their careers. Among many topics, the lab series covers practice with antidepressant consultations, but it did not address what to do if a patient expresses suicidal thoughts or urges.

They developed the Mental Health Skills Lab, seamlessly folding it into the existing series of skills lab activities. Now, all of the School’s student pharmacists are equipped with this training before entering their APPEs.

“Some people are scared to ask these questions about mental health,” Schirmers says. “But when you repeat those uncomfortable questions — like ‘Do you ever want to go to sleep and not want to wake up?’ — you get more comfortable and more confident asking. That’s really what I hoped would come out of this lab.”

Practicing compassionate conversations

“So often, pharmacists, especially in community settings, are in an isolated environment,” says Gallimore. “They don’t have mental health team members working in the same facility who they can reach out to when needed. They need to have that skillset to navigate those interactions on their own. In the moment, they have to know how to react.”

The class walks student pharmacists through the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), an assessment tool with questions to determine a patient’s risk for suicide and gauge an appropriate response. For example, “Have you wished you were dead or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up” and “Have you done anything, started to do anything, or prepared to do anything to end your life?”

“One thing that’s challenging for students is verbalizing these questions,” Bergsbaken says. “Practicing these conversations in class can make it easier in the future when they need to be prepared to ask directly, ‘Are you having suicidal thoughts?’”

Bergsbaken and Gallimore were careful to tackle such sensitive subject matter with care. They taught destigmatizing language around suicide, such as saying a person “died by suicide” instead of “committed suicide” and not referring to someone as a “suicidal person” but as “someone with suicidal thoughts.”

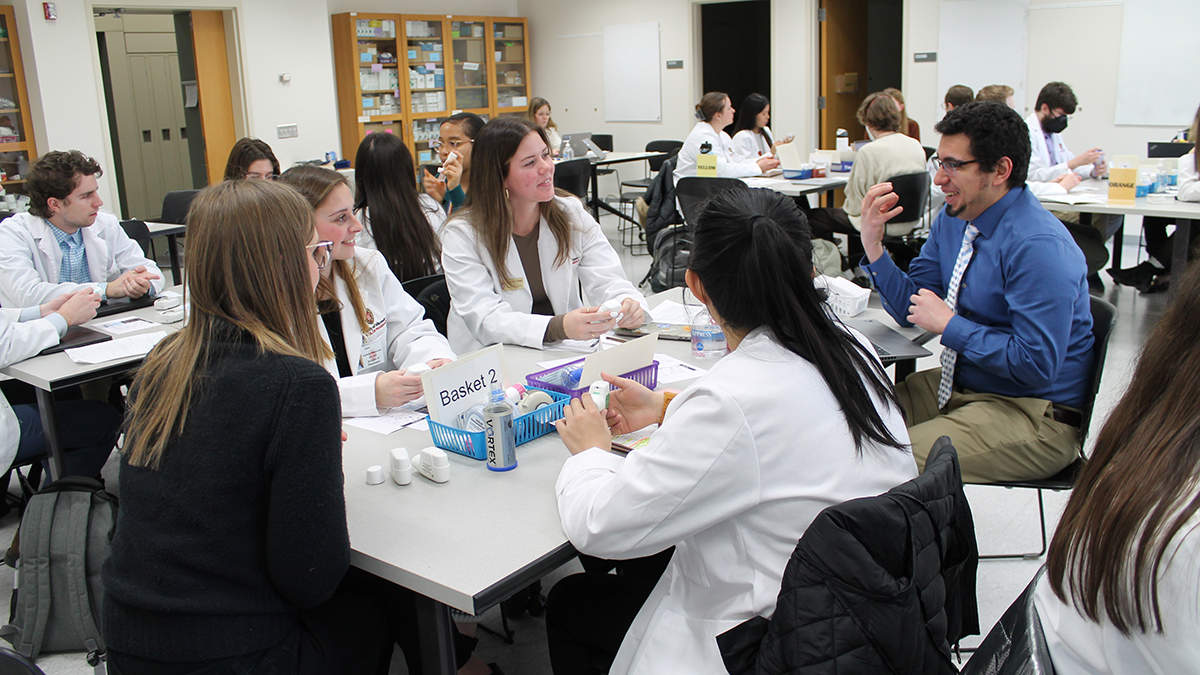

After the didactic portion of the Mental Health Lab, students go through practice scenarios where they directly apply the C-SSRS, ask questions, and determine a patient’s risk for suicide.

One example sees a community pharmacist encountering a patient picking up a new medication after a heart attack. The patient is exceptionally tired and struggling to do things that used to be easy. They express the desire to give up — a possible indication of suicidal thoughts — and the student asks appropriate follow-up questions to determine if this patient is at risk for suicide. Another example sees an ambulatory care pharmacist encountering a patient who no longer wants to live due to chronic pain.

“Having pharmacists trained to recognize red flags for suicide […] is an extremely important service for public health.”

–Casey Gallimore

“It’s really challenging, but the lab pushed us to ask those clear, direct questions,” says second-year PharmD student Dan Hill, who participated in the Mental Health Lab this year. “It showed me the importance of having these conversations, even if they make you uncomfortable. I’ve had friends die by suicide, so this really hit home for me. Going into pharmacy, I never expected to be involved in mental health, but even working as a pharmacy intern over the summer, I’ve already seen cases where these skills were useful.”

Extending the impact

And the skills learned in the Mental Health Lab apply far beyond just a pharmacy setting. Bergsbaken says that students have already told her that they applied the skills practiced in the lab with people in their personal lives.

“Pharmacists are one of the most accessible health care professionals,” says Gallimore. “We work in the community. We’re interacting with people. Having pharmacists trained to recognize red flags for suicide, to know what questions to ask, to be comfortable engaging patients in those conversations, and to be able to provide resources, is an extremely important service for public health.”