12

December

A cutting-edge platform uses protein-degrading platelets to suppress tumor regrowth and bolster immune response after surgery

By Eric Butterman

The primary treatment for breast cancer — the second-leading cause of cancer death in women — is surgery.

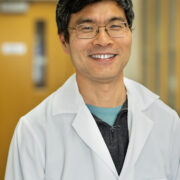

“Unfortunately, the recurrence rate after surgery is pretty high, particularly for the high-risk version of this cancer,” says Quanyin Hu, assistant professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy.

Through a new platelet-based technology he developed, Hu hopes to reduce breast cancer recurrence and metastasis after surgery.

“Our work centers on breaking down the proteins responsible for cancer recurrence and immune evasion through using an engineered platelet-based platform technology,” he says. “The outcomes have been very encouraging so far.”

After the surgical removal of tumors, platelets naturally go to the site of the wound and become activated to help with clotting and healing.

“When you consider the effect cancer has on lives, not just for the patient but for their loved ones, the work we’re doing is critical.”

—Quanyin Hu

“The platelet can actively accumulate at the post-surgical cancer site — and, in that way, we can lower the potential side effects,” says Hu, who runs the School’s Cell-Inspired Personalized Therapeutic (CIPT) Lab.

Through Hu’s platform, platelets are labeled with protein-binding molecules, called protein-of-interest (POI) ligands, which can target and degrade the proteins — intracellular and extracellular — responsible for cancer recurrence through two pathways.

The modified platelets, termed DePLT, can target BRD4 — a protein involved in regulating gene expression that supports cancer cell growth and survival. Once activated, the modified platelets release microparticles that transfer their interior BRD4 ligand-labeled effector proteins into the cancer cells, where they hijack the cell’s natural waste system that tags and degrades unwanted proteins.

“Intracellular protein-degrading machinery relies on the platelet-derived microparticles, and these microparticles will enter the cancer cell through membrane fusion,” Hu says.

The second pathway the modified platelets can take attacks the cancer cells from outside, by binding to PD-L1, a protein on the surface of cancer cells that helps them evade the immune system. Here, the modified platelets release PD-L1 ligand-labeled effector proteins in free form into the extracellular space, where they redirect those proteins to the lysosomal degradation pathway.

The CIPT Lab’s results, published in Nature Biotechnology, show strong positive effects, Hu says, though there is much work ahead.

“The survival time of mice is normally 30 days and, from our findings with the mouse model, the platelet therapy extended that survival time to around 60 days,” says Hu. “The platelets with POI ligands for both intracellular and extracellular targets suppressed metastasis or recurrence.”

This platelet-based platform is flexible, Hu says, and can be tailored for specific proteins that are implicated in other cancers and diseases.

“In our work so far, we only tested the proteins expressed for breast cancer, and we are going to expand the platform, such as to prostate cancer,” Hu says. “The other step is the vital move of testing the long-term toxicity of this platform.”

Hu’s lab is targeting cancer from several angles, including an injectable gel to prevent glioblastoma recurrence, hydrogels to enhance the body’s immune response to cancer cells, and nanodrugs on bacteria to infiltrate difficult-to-treat pancreatic cancer. Earlier this year, he also used the clotting power of platelets to storm tumors with immunotherapeutics.

“When you consider the effect cancer has on lives, not just for the patient but for their loved ones, the work we’re doing is critical,” says Hu. “It is technical work but it’s the people we are thinking about, the idea that we could possibly help alter lives for generations to come. That is what motivates the work and drives it.”