Since 2020, the Pharmacy Experts webinar series, created by the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy, has shared some of the School’s most innovative and far-reaching research, as well as the work of alumni on the cutting-edge of their fields, touching on population health, digital therapeutics, and more. The series’ eighth installment explores how psychedelic compounds are playing a new role in mental health treatments.

Listen to Cody Wenthur, associate professor in the School’s Pharmacy Practice and Translational Research Division and director of the master’s degree program in psychoactive pharmaceutical investigation, speak with Professor Dave Mott (BS ‘88, MS ‘92, PhD ’95), associate dean for Advancement, about the early stages of clinical trials using psilocybin and ketamine as treatments for challenging mental health conditions, as well as how the field is changing and growing.

Professor David Mott: Well good evening everyone, and welcome to the eighth installment of our Pharmacy Experts webinar series. The title of our webinar tonight is Psilocybin, Ketamine and Behavioral Change: Promises and Pitfalls for Psychedelics in Mental Health Treatment. I want to thank you for taking time this evening to join us for the webinar on this very interesting and important topic that will describe the results from ongoing study and clinical testing of psychoactive substances in treating significant mental health conditions.

The University of Wisconsin School of Pharmacy is at the cutting edge of this area of research and practice to the establishment of the UW–Madison Transdisciplinary Center for Research in Psychoactive Substances, and the establishment of the Psychoactive Pharmaceutical Investigation Master of Science Program.

The implications of psychoactive medicine for pharmacists, pharmacy practice, and patient care will be discussed.

My name is Dave Mott, and I am the associate dean for advancement at the University of Wisconsin School of Pharmacy and I will host tonight’s webinar. This event is being sponsored by the UW School of Pharmacy Advancement office. And I want to acknowledge and thank Alissa Karnaky, our alumni relations and advancement coordinator, and Jasmine Loving, our event coordinator, for their work marketing and producing our event this evening. We have over 130 people that signed up to join us for tonight’s webinar.

Before we get started, I want to describe the process we will use for taking questions. First, the chat function is turned off for attendees. Second, due to the number of attendees we will not be taking verbal questions. Instead, if you have a question, please use the Q&A feature on Zoom to type and submit your questions as you think of them. Since some of the questions may be the same across individuals, please feel free to click on the thumbs up icon to upvote for a question. Then during the Q&A session, I will read the questions with the most upvotes. This webinar this evening is being recorded, and we will send you a link when the recording is available in the next couple of weeks. We also will be sending you an evaluation of the webinar, so you can evaluate this webinar for our purposes. Okay, all right, let’s get started.

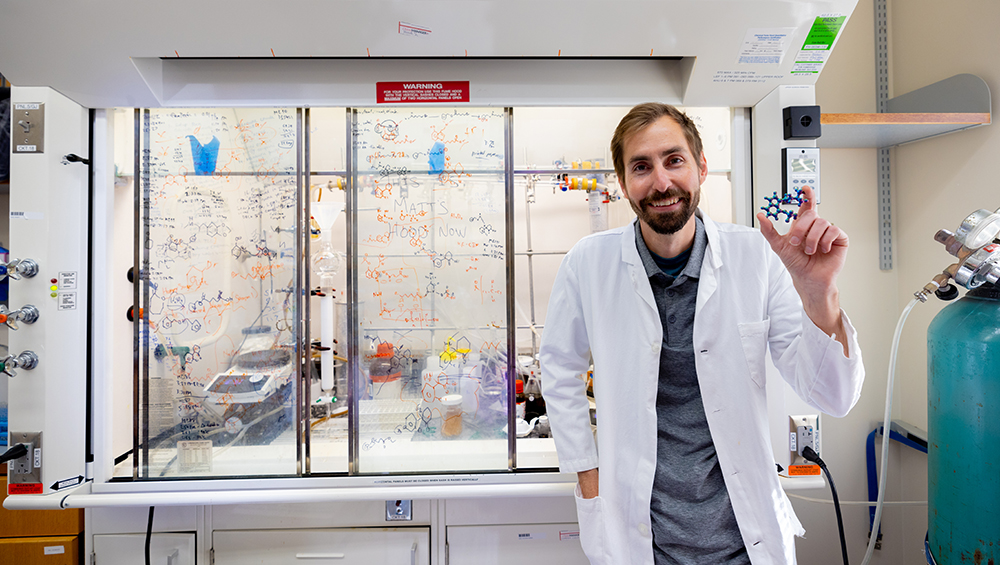

Our webinar presenter this evening is Dr. Cody Wenthur. Dr. Wenthur is an assistant professor in the Pharmacy Practice and Translational Research Division at the UW School of Pharmacy, and director of the first-of-its-kind Psychoactive Pharmaceutical Investigation Master of Science Program at the School of Pharmacy. Dr. Wenthur received his PharmD from Purdue University, his PhD in pharmacology from Vanderbilt University, and completed postdoctoral research at the Scripps Research Institute. Dr. Wenthur was named an innovative new investigator by the NIH in 2020 and was honored with the Vilas Early Career Faculty Award by UW Madison in 2023. Dr. Wenthur’s research focuses on ways to improve mental health care through the development of new therapeutic treatment approaches, specifically those that include opioids, dissociative hypnotics, psychedelics, and cannabinoids. His research is motivated by the staggeringly high reported rates of depression, anxiety, overdose, and suicide, inadequate access to treatment, and the failure of current therapeutic models to meaningfully improve the daily life of those who dearly need it. With that, it is my pleasure to turn our program this evening over to Dr. Cody Wenthur. Cody.

Assistant Professor Cody Wenthur: Thank you so much, Dave, and thanks to everyone for joining this evening. I’m really looking forward to the opportunity to share a little bit about this important area with everyone, as well as some of what we’re doing in my own lab, and hopefully leaving a lot of time for questions because I know there’s always a lot of great engagement around this topic. So with that, let’s get going.

I won’t spend a lot of time belaboring statistics on mental health in the United States, perhaps in part because the problems are fairly glaringly obvious to anyone who has spent any time in clinical practice or indeed out among the public. You can see some of the summary statistics here that give us a sense of where we’re at in terms of managing mental health. Up here we can see that almost 20 percent of American adults are experiencing a mental illness in recent years. About 15 percent of youth have experienced a major depressive episode in the last year. Nearly 5 percent of individuals have serious thoughts of suicide, and this keeps going up year after year for the past decades. And importantly, thinking about treatment and access in our role as pharmacists, more than half of adults who have a diagnosed mental illness aren’t even currently receiving treatment for that disorder, and this is about 27 million Americans. So if you add those together with the ongoing opioid epidemic, and again, the continuing increase in suicides across the country, I think it’s not challenging, or there wouldn’t be a lot of disagreement around the idea that we can and need to do better in terms of treating those around us who are who are struggling.

Tonight, you saw the title of my webinar, and we’re talking about psychedelics, and the questions you know are going to come up: Why are psychedelics even relevant to this problem? But first, we’ll sort of introduce the cast of characters. What are psychedelics? And here we see the origin actually of the word psychedelic. So, this is coming from a physician colleague up in Canada, Humphry Osmond, who was a psychiatrist working on some early LSD trials for alcoholism. And, at this time, he was in correspondence with Aldous Huxley, noted intellectual and author in the United States. They’ve been experimenting with mescaline, as well as LSD at this time, and were trying to come up with a name, right, for these compounds that were seeming to do things that were not very well understood or discussed in Western medical literature at the time. And in letters back and forth, eventually what they landed on was this couplet: “To fathom Hell or soar angelic, just take a pinch of psychedelic.” And this is the first time we see this word come up, and the word was coined as a neologism from these Greek roots. “Psyche,” meaning mind and “Delos,” to make manifest. The idea being that these compounds make manifest, make obvious the inner workings of the mind in a way that make them subjectively apparent to folks who are taking them.

As Dave mentioned, my lab is very interested in psychoactive compounds of many stripes. So let’s dig in here a little bit on what compounds we’re talking about when we say psychedelics. So, here you can see the drug wheel of psychoactive compounds divided into the stimulants, depressants, et cetera. And on the right-hand side here in green, we see the psychedelics proper, including compounds like LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, and DMT, as well as other newer analogues that have been developed by medicinal chemists over time, and also this interesting compound 5-MeO-DMT, which is the only psychedelic known to be produced by an animal: the Colorado River toad.

For the purposes of this talk, you’ll see I’ve expanded the wedge just a bit. As a pharmacologist, I do think that MDMA is best classed as an empathogen and entactogen. Ketamine is well classed as a dissociative hypnotic compound. In a lot of the public discourse that you’re hearing about psychedelics right now, these two compounds are being lumped in with other psychedelics, largely because they’re being used in experimental new models of care that are mimicking those that are being used with psychedelics. And actually, one might argue that ketamine is the forerunner for this whole area and kind of creating the new wave of excitement in this. While they’re not strictly psychedelics, these compounds certainly will be discussed this evening.

So we talked about Humphry Osmond a little bit right in the middle of the 20th century, which of course, is you know, longer and longer ago than it ever was. And there’s a lot of discourse in public thoughts around psychedelics in the 20th century, for good reason. So some, you know, certainly interesting things happened in the 20th century: identification of the structures of psilocybin, creation of LSD in the 1970s, passing the Controlled Substances Act, not to mention all the countercultural activity in the 60s. And we also have a lot of discourse around things in the 21st century in the so-called psychedelic Renaissance, where we’re using the tools of molecular biology, genetics, and an ever-increasing sophistication with organic chemistry to try and understand the mechanisms that are supporting these compounds.

But, the thing I really want to draw your attention to on this slide is here on the left. So, although this timeline goes back nearly 100 years, the vast majority of human experience with psychedelics is actually used by indigenous populations, and we have anthropological evidence suggesting that at least 6000 years of continuous use for some of these substances in human societies for ritual and cultural purposes. I don’t say that lightly, because lots of actually the key elements that are coming into the psychedelic assisted therapy trials can trace their lineage, you know, directly or indirectly, to this knowledge generated and maintained through the traditional uses by indigenous people and the cultures that they support. I think any conversation of psychedelics is certainly missing a great deal if it doesn’t engage with the long history of these practices and the ways in which even today, the medical model is building off of that hard won wisdom.

So that gives us a little bit of a primer around what psychedelics are. Now, let’s dive into some pharmacodynamics. Right, so these compounds are being taken by people in the context of clinical trials ,in the context of religious or sacramental use, in the context of wellness, recreational use, but ultimately, they’re all getting into the body and acting on our biological systems in order to create some changes. So the question is: what are those actions? How are they creating these profound alterations in perception?

And we’ll start here. We’ll start with the psilocybin molecule binding to this G protein coupled receptor. So a membrane receptor hanging out on the outside of neurons, ready to respond to things in its environment, and the receptor we’re looking at here specifically is the serotonin to a receptor. The natural ligand for this receptor is, of course, serotonin. But, it doesn’t take a great degree of chemical sophistication to notice that LSD and psilocybin have structural elements, particularly this amino tryptamine compound. Now, this aminoindole looks pretty similar to that of serotonin. So LSD and psilocybin bind with fairly high affinity to add a serotonin to a receptor in order to turn it on. Now, that’s not the complete story by any means. They also bind to many other of our serotonin receptors. LSD and other ergotamine compounds also bring in some dopaminergic activity. There’s no adrenergic activity on board for some of these, even a little bit of histaminergic activity.

But the 2A receptor gets a lot of attention now because if you are to block that receptor with another agent, Ketanserin is classically used to do this, people no longer report the profound changes in consciousness that they otherwise report under the influence of these compounds. So certainly interesting polypharmacology, but if you only remember one receptor from tonight, I would encourage you to remember serotonin 2A. Turning that on is a really important thing that psychedelics do.

Downstream of that binding, the story to me gets even more interesting, because I just told you that serotonin is binding to the 2A receptor, just like psilocybin, just like LSD. But certainly, even though you have serotonin, activating 2A receptors in your brain right now, even as we speak, waking consciousness is very different than consciousness under the influence of psychedelics. So, how could that be? If serotonin is acting on this receptor all the time, why aren’t we having a psychedelic experience all the time? And we don’t have the complete answer to that picture.

But one, I would say, very intriguing hypothesis that’s out there is this concept of biased agonism — that when a compound binds to the receptor, it can activate multiple pathways. Maybe this is a G protein pathway, maybe this is an arrestin pathway. But depending on the compound, it can take this receptor and a slightly different conformation that prefers one pathway and ignores or at least reduces signaling through the other. You can imagine that a third compound, right, that reverses this where we get signaling through pathway B, versus pathway A. And indeed, if we look at a pair of compounds here, R-Lisuride and LSD, which, again, are obviously structurally quite similar at first blush, you just reverse this amyloid and you methylate here, but otherwise, very similar looking compounds. Both activate the 2A receptor, and yet, R-Lisuride has no psychedelic properties. LSD, one of the best known and most potent psychedelics ever discovered by humans.

And if we look at testing this idea that biased agonism may have something to do with this, we can look at this plot of activation of two important neuronal activation markers downstream of receptor signaling. One of these is called egr-2, the other is called c-fos. Now, it’s not important that you memorize those, but if we take a look at our R-lisuride, S-lisuride, and ergotamine, all of which are non-psychedelic, and we draw a line vertically on the x axis here, you can see that they are activating c-fos similarly to all of these compounds up here, some of which we’ve already mentioned, others are analogs that are all psychedelic. But, if you try and draw a singular line over to the Y axis, you can’t draw any one line, right, that goes through these compounds. They seem to activate egr-2 to a very different degree. And while this isn’t a smoking gun or the final say, I think it is really interesting and compelling evidence that there may actually be something to the fact that psychedelics are putting this receptor into a confirmation that it can activate different pathways, then compounds which activate the receptor, but don’t have psychedelic properties.

So after all that intracellular signaling is going on, what else are psychedelics kicking off? Here, we’re looking at DOI, DMT, and LSD. And these little spidery diagrams you’re seeing here are actually cartoons of individual neurons growing in a dish, and you can see their cell bodies, you can see the neurites growing out. And what you’ll notice, as you look at these, is that the compounds that have been treated with the psychedelic compounds seem to have more of these neurites growing out, they have more branching points. There are formal analyses that you can do on this, that indeed, show with long term incubation of these compounds, you get structural reach. You get changes in the structure of neurons, and the points at which they connect with one another.

There’s also meaningful changes in structure, in that there’s growth of additional spines. The spines are what’s on the neurites to reach out and make connections, potentially form synapses. If we look at markers of things that we would expect to be in a synapse, at that point where neurons are talking to one another, you can see the growth of more synapses in the presence of DOI, DMT, and LSD. So, in addition to signaling now, we see some evidence that we’re actually inducing structural plasticity. There are lots of compounds that can induce plasticity. There are lots of experiences that can induce plasticity. But, when we’re thinking about the ways in which behavior changes, it’s good to see, certainly, that these compounds are inducing plasticity, because we would expect that in compounds that are inducing behavioral change.

If we zoom out on another layer, and now instead of looking at the single cell, now we’re looking at networks of cells in the human brain, we also see systems effects, network effects when psychedelics are actively on board, in people’s brains. And in the working brain, there are nodes that are often in communication with one another during particular tasks, like the executive control network when you’re performing a complex task that requires pre-planning or thoughts. There’s also networks like the visual network, which are being activated as you look at the slides. The auditory network as you listen to my voice. And then networks like the default Mode network, which turns on if you close your eyes, sort of quietly turn your attention inward.

Connections between the various nodes and these networks can be shown in a graph like the one we see on the right here, where each of the individual nodes is a brain region. And then each of the lines connecting those represent connections between those brain regions where they’re likely to communicate with one another, and the weight of that line indicating the strength of the connection. And what you see here in the placebo condition, is that these have been clustered along standing networks that are likely to communicate with one another when particular tasks are engaged with relatively few long-range connections between the standing networks. If we move over to the psilocybin condition, we see a very different pattern, where there’s this almost anarchic pattern, brain regions that normally are not in strong communication with one another, or at least are unlikely to communicate with one another actively at the same time, now become much more likely to do so. You get sort of disintegration of the standing networks during the peak drug effects. That’s been postulated to lead to effects like synesthesia, where you can hear a color, or you can taste a sound, for example. That has yet to be rigorously proven, but certainly this sort of anarchic or chaotic pattern that we see underneath psychedelic administration is an interesting phenomenon that definitely bears following up on and there’s quite a lot now od functional MRI neuroimaging work that’s going on with these compounds, to help us better understand this phenomenon.

Now, of course, if we zoom out to the final layer of what is it like to have a psychedelic experience, we can map out various dimensions of this experience, like the synesthesia that I just mentioned, audio visual, being a very common one. And then changes in visual structure, and other things that are often less noted in sort of popular descriptions of psychedelic use. But changed meaning of perceptions, that things have enhanced or really intense meaning, is often a very strong feature of psychedelic experiences We can map out things like insightfulness, religious experience, experience of unity, bliss, as well as negative things like anxiety, impaired controlling cognition, senses of disembodiment. And as a scientist, it’s important for me to be able to take this what can be a very difficult experience to describe. Some might say ineffability is actually a core feature of psychedelics. But to be able to have people reliably and reproducibly report changes in perception, there are a bunch of tools here that you can see on the left that have been generated to do exactly this, to have people measure how their consciousness has changed underneath the influence of psychedelics.

In this plot, we see increasing doses of psilocybin as we go from the red to the green to the brown, and you can see the scale here going from 10, up to 70. As people have higher endorsements of these effects, they’ll go further out of the plot, and what’s nice to see here is that there seems to be a good dose dependent effect, and the overall shape of the experience seems to be reproducible between compounds, which makes this a useful pharmacological tool. And again, we don’t have the final picture by any means of how this is all ultimately leading to change. But, I would propose that interactions between each of these layers directly at the neuro layer and the perceptual layer, the network layer, are likely to coordinate to lead to the sorts of long term behavioral change that people will report and that we’re starting to see evidence for in clinical trials.

So to me, that always brings up this question: are drugs alone really enough to produce real changes in mental health? And I think the evidence for folks who have substance use disorders is pretty compelling to suggest yes, that drugs, in the right circumstances, can have profound effects on people’s mental health, often in a negative way. But in the context of psychedelics, the model is not really proposing that drugs alone are causing changes that are more adaptive or for the better. It’s being embedded within a system of therapy administration.

If we think about those mechanisms we just talked about, this is one model for how psychedelics might be helping to catalyze those long-term improvements in mental health. So here again, if we treat each of these nodes as representing areas of the brain that are in communication with one another, I mentioned the default mode network, which is turned on when you’re sort of introspecting and quiet. There’s some pretty good evidence that folks who have things like major depressive disorder can, on average, have stronger connections between regions within the default mode network, and they can exhibit these patterns of a cognitive rut. And there’s an old saying in neuroscience: neurons that fire together wire together. So you can actually get enhanced connectivity between these regions that reinforces that cycle. And so if we think about what we said about how psychedelics may work, acutely, they could be weakening old connections, helping to form new connections, and potentially right in the right context, this could help lead to cognitive escape, where you have new pathways to work with and on. But just because you’ve made new pathways doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re going to get better or that there’s any valence to that direction.

So this is why current psychedelic trials have looked quite a bit different than most clinical trials that you might see for other psychoactive compounds, which is that there are often two therapists involved within this, they’re actively supporting the individual during the psychedelic experience. There’s also a bespoke room here, you’re seeing the study room at the School of Pharmacy itself, that looks a lot more like a living room than it does like a clinical environment. And, again, a lot of this is drawn not only from knowledge that was won in the 20th century. In some cases, very hard won in quite unethical ways, such as an MK Ultra experiment where people were unwittingly given psychedelics, and had very bad experiences, but also, again, through evidence drawn from centuries of indigenous knowledge. And that psychotherapy support really comes in three main phases, which is what we’re looking at here.

Here, this is a study diagram for the MDMA assisted therapy study, where you can see there are preparatory sessions ahead of time where the study therapist is meeting with the individual in order to allow them to understand the person’s problem, why they’re here, help give them information about what to expect, when the drug is being given, what potentially the goals of the patient are, in order to improve their symptoms. And then you see an experimental session here, which is when the drug is being given. And that’s followed by three integration sessions where no drug is present, but the therapists are working together to talk through insights or challenges that came up during the experimental session. And you see this repeated in three blocks.

So it’s a pretty rigorous and intense protocol for patients to ask. I think there’s something like 17 study visits overall in this model. And so, in addition to the drug, there’s also therapist training and experience that’s going into these trials. I mentioned the preparation orientation sessions, development of therapeutic alliance and trust has been shown to be an important actual mediating factor in the therapeutic direction of these compounds. The integration, and all of this, again, is wrapped up in a set, a mindset, development, a setting, and a support system.

So the model is really one out of psychedelic assisted therapy at present. There certainly are companies like MindMed, who are looking at it trying to minimize the role of that therapy component, given the challenges that may surround its implementation. But right now, that’s certainly an empirical question and we’re really looking at the dominant model. So the question is: what evidence do we have that psychedelic assisted therapy might actually work to improve mental health? What’s the state of that evidence right now?

The first compound I’m going to talk about is ketamine. So ketamine in the form of esketamine was approved for treatment resistant depression back in 2019. This is SPRAVATO. It’s an intranasal formulation. Since that, we have seen across the country, proliferation of intravenous ketamine clinics being used off label for the treatment of depression. Something like 500 ketamine clinics are around the country right now. And if we look at this meta-analysis data, here looking at ketamine in treatment resistant depression. I believe this is a combination of intravenous studies and intranasal studies, where ketamine is better if it falls on this side of the line, placebo is better if it falls on this side of the line.

You can see that there’s a rapid, significant improvement within one day with ketamine over placebo. And that persists up to seven days later, which is quite exciting and interesting. Certainly a different profile than we see with classic antidepressant compounds like SSRIs, which for many folks don’t, have full effect for six to eight weeks, and often people need to try multiple rounds of therapy before they find a medication that works for them. And estimates are, you know, actually a third to half of patients, even with four rounds of therapy, don’t find a current medication that works for them, and so it’s notable right that this is occurring in treatment resistant patients.

The other area that ketamine has had, I think a big impact is on individuals with suicidal ideations. So there are those black box warnings, for many antidepressants, where they’re potentially activating folks early on in drug administration time course. Particularly adolescents and young adults have seen rates of increased suicide early in that treatment time course. Whereas ketamine, and esketamine, again, are showing unique benefit here in treatment of individuals suicidal ideation, which was why a second indication eventually was given to the esketamine for this particular evidence. So this one is definitely the furthest along in evidence. It was considered strong enough to get approval. And we do have a clinically usable therapeutic on the market right now.

Now we’ll move to some other, more exploratory areas. Here we’re looking at psilocybin data, and over the next couple slides, we’ll stick with psilocybin for a bit. This study was one that really got the field very excited about the potential for psychedelic assisted therapy to make a difference in patients’ lives, where folks were being enrolled into the study, because they had an end of life, terminal diagnosis, that also came with a secondary diagnosis of anxiety, or depression, secondary to that threat to their mortality. And we don’t really have drugs labeled for existential distress. But this, of course, you know, is extraordinarily destabilizing for patients and very challenging.

Now, this study was looking at a single dose of psilocybin with therapy, and measuring the effect on these individual’s depression scores, anxiety, and other things like total quality of life. And in this study, they either got a high dose of psilocybin one considers to be effective, or a very low dose. I think it was only one milligram. Basically, such that you could say everyone was getting psilocybin the study at each point, but not that we thought enough to be efficacious. And what you can see here is a very rapid and dramatic decrease when folks get that singular high dose of psilocybin. Now with the sudden setting protocol, there is a pretty big placebo effect here, which we see in a lot of antidepressant trials. But they were also getting therapy, so there could be a component of that. Then, when they get the high dose, most folks end up down here. And they get no more drugs after that, and in this study, the effects persisted for up to six months. The line that I’ve drawn here actually represents the line for remission of symptoms. And there’s now a four and a half year follow up study, where something like 70 percent of individuals remained in remission at that time, for those individuals who survived with no further dosing. You can also see strong effects on overall quality of life here.

And as you might imagine, this got people very excited. They’re thinking, “Oh, wow, it’s a one and done shot. It’s a miracle cure. It’s lasting people the rest of their lives.” And I think that was sort of the dominant discourse for a minute. But as more evidence came out, and more other disorders came to be looked at, that has definitely shifted, I would say quite a bit. There might be something uniquely powerful right about overcoming that existential crisis or mental health that is persistent, whereas something like major depressive disorder, which is a chronic relapsing disorder, we’ve seen good effects of psilocybin in treating this. So here there was a single 25 milligram gram dose of psilocybin that was compared to this active placebo niacin, and it was significantly reducing major depressive scores at 43 days afterwards. I will note, Chuck Raison is here at the School of Medicine at University Wisconsin and an active member of our psychedelic center. We definitely were a research site for this very important landmark study. But after 43 days, right, this effect sort of started creeping back. And so in something like major depressive disorder, at least in my estimation, it doesn’t seem likely that there will be a single dose right or a single bout of treatment that lands people into complete recovery.

For treatment resistant depression, here we see a study for COMPASS, where we’re giving either one milligram, 10 milligrams, or 25 milligrams of psilocybin, you again, see, you know, a pretty rapid and large decrease on the very first day after treatment. But we lost significance here after week six. This was the last point at which the effect was significant, and by week nine, this, although numerically, obviously is different, was no longer statistically significant. So I think there are definitely going to be, you know, lots more studies and work needed to be done with regard to how do we prolong the effects of the single treatment, what really is the total efficacy time course we can expect for a single treatment, because with this intense and resource intensive of a protocol, that makes a huge difference in the potential pharmacoeconomic benefit, and frankly, the burden and accessibility of care for this type of a model.

Just one more study with psilocybin. Now, before we move to MDMA, we can look at psilocybin for alcohol or tobacco use. Definitely among the most exploratory trials, this trial on the left was looking at drinking outcomes with psilocybin. So here, they received two doses. And you can see improvements in heavy drinking days with the psilocybin as compared to their active placebo, which in this case was diphenhydramine. And there were also significant influences on things like complete abstinence and other important factors. But this was only about 40 to 50 patients per arm, so definitely early days to see if this is replicable. Even a smaller study that is being followed up on right now, looking at cigarette smoking, with a single dose of psilocybin with therapy, seeing very strong reductions in cigarette smoking up through the endpoints of the study, here where there certainly are some people creeping back up in use, but there’s a whole bunch of folks down here who stopped smoking entirely. Again, we’re only talking about 17 or so folks. So very, very early evidence. But, definitely part of the reason why there’s been such interest in this use case.

And then last, we’ll talk about MDMA assisted therapy for severe PTSD. So UW was a site for the phase two and phase three trials for the study of MDMA assisted therapy for PTSD. What we can see here is we’re looking at the number of responders, those who have loss of diagnosis and those who have remission in the trial. Remember, they got three sessions of MDMA in this particular trial design. So these are folks who got therapy only, and then these bars are folks who got MDMA added on to their therapy. The top line results for this study did look positive for MDMA, where 67 percent of the MDMA group didn’t meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, whereas only about a third for placebo met that condition. About a third of the MDMA group met the criteria for remission, whereas only one out of 20 in the placebo group met that criteria. So this certainly got people quite excited. This is a phase three trial and MAPS was going ahead to the FDA to request approval. And with that, we will definitely pick that story up right here.

So that’s all the good stuff that’s, you know, what we think is a potential benefit. The questions are what challenges and risks are associated with this approach? And right now, I think there is a question about whether the data is sufficient to actually understand what the benefits and risks are. The psychoactive compound advisory group from the FDA recently reviewed MDMA and did not find there was sufficient evidence to say that it was effective or safe in comparison to placebo. And that happened just seven days ago.

This Psychopharmacology Advisory Committee brought up a couple areas of concern for sure. Number one was functional unblinding. So I kept saying, you know, this is in comparison to an active placebo. And there’s been a lot of attempts to try and create trials, where you use a placebo so that people can’t tell they’re getting a psychedelic, and these have been basically virtually entirely ineffective. People can usually tell, right, that they’re getting a psychedelic. And the team had concerns about the effects of that on the outcomes of the study. They also brought up that there was limited long term efficacy data. There was certainly some follow up studies done with MDMA assisted therapy groups, but responders tended to naturally stick around in those long-term studies, whereas non-responders did not. So there were questions about selection bias in those studies. And really another one is this sort of unclear contribution of drug versus therapy protocol. There haven’t been other drugs that come up in front of this panel that are billed as a combination of a drug plus the therapy. Now, and in this case, it’s a little bit more compounded in that the therapy is not acceptance and commitment Therapy, or cognitive behavioral therapy or another well known, validated, approved therapy modality. It’s a bespoke therapy created for this protocol, and there were questions about how rigorous that was, how reliable that was.

Some other things that came up were kind of easy misses, honestly, from both sides. There was some missing clinical lab data there. The FDA missed this one, as did the sponsor. Some very serious concerns regarding sexual abuse and misconduct allegations that therapists, or at least one therapist in the study, was abusing a patient, despite the fact that there were two therapists present. And then concerns about diversion. And overall, I think, you know, there were some folks who weren’t concerned about this advisory committee meeting, because MDMA did have a breakthrough therapy designation, so they had robust access to FDA with pre-agreed upon study designs. And so these questions about functional unblinding and the drug versus therapy protocol, for some people, came a little bit out of left field, because the FDA themselves signed off on this very study design, although the advisory committee didn’t seem to think it was sufficient. And certainly, now we’ll see whether the FDA follows the advisory committee recommendations. It’s not binding. But I do think that these recommendations are useful for the field because ultimately, of course, we want patients to only get therapies that are safe and effective, and I think enhanced rigor is something that I certainly welcome and I’m excited to have come to the fore in this field.

There’s already some groups that are addressing some of these issues, such as the functional and blinding. People are doing dose response study design. So you saw this with the COMPASS trial where everyone’s getting the active drug, and we’re looking to see if there is truly pharmacological signal of increase of signal with increased dose exposure. Certainly, stricter tracking and reporting of prior ongoing psychedelic use to assess the expectancy bias, I think is something that the field would benefit from immensely. I think we’re gonna see moves toward more clear definitions of therapy and protocolization, and likely incorporation of actual accepted therapy paradigms alongside drug use to get around some of this lack of clarity that’s existing with this protocol. The REMS are going to help I think a lot with the questions of safety and the ways in which, where, and how these compounds will be used.

And I think overall, we just need less psychedelic exceptionalism from both sides treating these compounds, as you know, entirely different than other compounds. We need to throw the rulebook out and everything is new. I think it hasn’t been helpful from either side. It hasn’t been helpful for those folks who want there to be a rigorous, safe, and effective process to evaluate these, but it also hasn’t been helpful for the skeptics, where for issues like functional unblinding, for example, this is being treated as if it’s an entirely new problem that’s completely unsolvable. Now, whereas if you think about studies of pain medications, or sleep, medications, anti-psychotics, even things like devices, it’s very clear, if you got a hip replacement, there’s no way to blind that study. And yet, we can rely on empirical outcomes data. And so I think, in general, having the fields merge more with the standards, and also, stopping treating these compounds as uniquely frightening will be helpful from both sides.

So other things that I would point out that do occur in these trials that you might think about, elevated heart rate and blood pressure are pretty commonly reported within these trials, but resolving usually about an hour and a half afterwards. Lots of people get a headache after classical psychedelics, treatable with oral Tylenol. Nausea is quite common. Now, I think the other thing to point out as we were just looking at MDMA, and I think MDMA as a compound that has a slightly different mechanism of action, where it’s actually causing serotonin release and other neurotransmitter release, rather than just acting at the receptor, does induce some additional risks beyond those that we tend to see with classical psychedelics that you can see here. And I think the other thing that’s really worth mentioning, is although they seem to be very rare outcomes, currently, a small number of individuals are reporting delayed or lingering psychological symptoms, strong destabilization, even things like a first episode psychotic break, that are obviously extremely debilitating outcomes, and as access to psychedelics increases, the rate of these adverse effects is also likely to increase. That, as always, is balanced against the benefit that’s being garnered on a population level.

If we look at psychedelics in relation to other compounds, here, we’re looking at a harm score, harm to users and harm to others. We can see that LSD, mushrooms, and other psychedelics tend to be on the lower end of the scale, whereas things that are widely accessible, including alcohol, are causing, you know, much more direct harm. I think there will need to be a reckoning of our current scheduling system. By statute, if these compounds were to be approved for use, then they could not by definition, be in schedule one. And we saw actual movements toward this, and we’ll probably continue to see changes in scheduling, with marijuana being recommended to be moved down to schedule three, for example.

But harms do happen. And if we look at non-clinical settings, bad trips, people having acute psychological destabilization is definitely one that’s reported a lot. And in contrast, the well-controlled clinical trials where we see, you know, less than 1 percent of people sort of reporting these serious outcomes. A lot of folks taking these other situations are having much higher rates of these risks, with 11 percent reporting putting themselves or others at risk of harm, two and a half being physically aggressive or violent, two and a half getting medical help. And then again, a fairly high proportion of people in this study, which was self-report, so there’s likely some selection bias here too. But, a good number of people reported seeking treatment for psychological symptoms. So again, thinking about the medicalization process and the changes in non-medical access to these compounds, all are worth bearing in mind when thinking about the relative burden of of adverse effects, as well as potential benefits where folks accessing these outside of the trial context do seem to be having higher rates of these negative outcomes.

There certainly are good evidence for how to mitigate this risk of harm. So risk factors for dangerous behavior include a history of psychiatric disorders, inexperience with a drug, poor information, combination with drugs or alcohol, or use with unknown or untrusted individuals. And these two groups are very good harm reduction groups that address the harms that are occurring with psychedelic use in the wild and certainly good potential referrals for pharmacists. So I’m going to move through this very quickly so that we have time for questions. I wanted to give everybody a good sense of sort of the general state of the field before talking about some of the specific stuff that we’re involved in. So as I say, I’ll breeze through this pretty quickly to leave time for questions. But, hopefully you get a flavor of the sorts of things that we’re looking at.

So one of the main projects in our lab is looking at combinatorial contributions to ketamine as antidepressant effects. Essentially, we’re trying to ask the question, if this metabolite to our six hydroxyzine, or ketamine, is adding value to the antidepressant effects of ketamine? And in order to do that, we’re creating these haptens that are linked to proteins that cause an immune reaction, which basically tricks the body into making antibodies that can recognize hydroxyzine, or ketamine, shown here, or ketamine shown here. And using that to basically keep one or the other of these compounds out of the CNS, measure the effects that arise, and then logically deconstructing that, for example, ketamine alone is causing effect B, but the combination together is causing the effect C. So we’re doing that in preclinical studies right now. And we’re also applying this to try and map out the areas of neural activation that are occurring with one, the other, or both, as well as structural and functional changes in activity in cells in a dish.

Another exciting study that was just published as a preprint today, in collaboration with a number of other folks, including Paul Hudson, also in the School of Pharmacy, is this study looking at removal of memory for the psychedelic experience and looking at whether it still has long term outcomes. And in this study, here, we’re measuring the change in the altered state of consciousness. And we’re giving psilocybin with Midazolam, IV Midazalom dose, where we think we’re inducing amnesia. This indicates that we’re probably not blocking the acute psychedelic experience, but we are blocking their memory for that psychedelic experience. So here, as we go up in midazolam concentration, we get a decrease in their D prime or their ability to detect, for example, one statement that they did give on the day of dosing versus one that we made up and they didn’t state that they were having that experience, but they can’t discriminate between which one they provided and which one was the foil. And we see that, you know, this is recovered by day eight. So we haven’t completely removed memory, but we’ve definitely impaired it. And interestingly, if we look at long term outcomes, like emotional breakthrough inventory, persisting effects questionnaire, whether they had a personally meaningful experience, or in whether it’s led to changes in their personal life, we see hints certainly, that at these higher doses, were folks that had impaired memory, we’ve broken something that there doesn’t seem to be this long lasting effect. And we’re looking forward to continuing to work with that.

We’re also very interested in the role of psilocybin with stress and therapeutic outcomes. I see we only have five minutes left, so I’m going to stop with the details on this. But certainly, we have some interesting preclinical data indicating that resolvable stress may not be a significant issue. And if you’re interested in our work, diving into it in a little bit more detail, you can take a screen capture of this, to look at some of the papers that we’ve published recently and the ways in which we’re contributing. Also, as Dave mentioned, we have a very active research center with members from across campus and you can check out what we’re doing here at the Center website. You can check out our training opportunities at the URL below. And ultimately, we have, you know, serious mental health associated issues. There’s positive data in clinical trials right now, but definitely more work to do and special challenges that are rising because of the way in which this sort of paradigm shifting approach is being framed. There’s definitely risks for people when they are using them without knowledge. And ultimately, we’re quite interested in understanding not only the molecular basis for how these work, but how the non-drug elements of therapy are interacting with the drug, so that we can improve their effectiveness and safety. Lots of people in my lab and beyond have contributed to this work. And with that, I’ll stop and take some questions.

Mott: All right, Cody, thank you. And I encourage attendees, if you have questions, please use the Q&A function to add them in there. There are a couple in here, Cody that I’ll ask. The first one is a very broad question about the MDMA assisted, or the MDMA decision. So the question is what do you expect will be the impact on the field of the recent FDA Advisory Committee decision on MDMA assisted therapy?

Wenthur: Yeah, I think the impact on the field, the first effect is likely going to be that companies like COMPASS and MindMed and not-for-profits, like Usona, are gonna run back to the FDA, because they also have Breakthrough Therapy Status designation for their compounds and say, “You know, hey, you signed off on our trial designs too. How, when, where can we improve these study designs such that this same apparent disconnect between the Advisory Board and the folks they’ve been talking about at the FDA, such that that hopefully doesn’t occur. And I think the other thing that’s likely to be another big impact on the field is, again, the much, hopefully, more crystallization around the therapy components of the intervention, where it’s more rigorously defined, and we can better understand the contribution of the drug, versus the therapy, versus their, their interaction. So I think those are going to be two major effects. I think there’s not likely to be a rapid exodus in this space. There’s certainly a lot of folks looking for novel psychedelics or psychedelic light compounds. And I think that this may accelerate that, particularly for those folks who are looking for compounds that have altered or reduced subjective effects to try and mitigate some of those unblinding considerations as well as you know, the risks that arise from that.

Mott: Second question, sounds super interesting to me is, are there any known genetic or pharmacogenomic implications with psychedelics?

Wenthur: Great question. So I’ve been working with two current pharmacy students to generate a paper looking at drug interactions with psychedelics, because it hasn’t been nearly as explored as it should have. And certainly as pharmacists, this is an area where we can make great contributions. Lots of people already are accessing psychedelics in the wild. And there has been one study looking at LSD and pharmacogenomics, where variations in suplity-6 seem to modify some of the exposure profile to LSD and 3A4 as well. There haven’t been a lot of studies with sort of pharmacodynamic effects of varying genetic backgrounds. But, it wouldn’t be surprising if there were, you know, not only effects on sort of the intensity, but also potential of highly genetic effects on things like risks. So in the clinical trials, people with a first degree family history of a psychotic disorder have basically uniformly been excluded from these trials. And I think, you know, if you look at the risk literature, folks who are having what look like, you know, first time psychotic breaks often do have a familial history of schizophrenia and other things. So, that would seem to indicate there may be a genetic risk factor for some of these serious negative outcomes, but that’s definitely underexplored. I think pharmacokinetic information downstream of pharmacogenomic studies is going to be the next sort of low hanging fruit in that area.

Mott: Alright, I think we have time for one more question. This is a good one too. Given the limited patentability of these compounds and thus less interest from big pharma, how do you see these treatments getting the financial support to run the expensive trials needed? Is there interest from industry in potentially patentable analogues or novel delivery systems? Or would non-industry development be more likely?

Wenthur: A fantastic question. I’ll take it, I think, piece by piece. So, yes, there is certainly strong interest in novel analogues of these compounds. And they just bought Gilgamesh, which is a company that is developing new chemical material around sort of classic psychedelic scaffolds. And they’re just one of many, that’s just the example that came to mind. And that presents a much more traditional development pathway. Now, also, there’s a lot of folks looking at other bendable approaches, like alternative delivery methods, or things that are again, sort of classical drug development. And then for the other side of the equation, are there models for, you know, non-pharma to bring these through, given how expensive it is? So, yes, those models do exist, MAPS started out as a not for profit. They made it all the way to phase three before they essentially ran out of donor money and had to spin off the pharmaceutical company Lycos to finish it off. So, they didn’t get all the way there, but they got further than any other not-for-profit has. Usona institute here in Madison has started their phase three clinical trial of psilocybin for major depressive disorder continuing to operate as a not-for-profit. So, I think this does represent a potential opportunity, you know, for things to be done a little bit differently. That being said, MAPS didn’t get it all the way to the finish line. We’ll see what happens with Usona and others, because this is a very expensive process. And there’s been a lot of tension, honestly, in the field around sort of trying to move therapies that people believe in through the rigorous process without appealing to the usual capital structure. And the need to do very strong, rigorous, and intense studies to provide the evidence base that these are indeed effective and safe, and that we shouldn’t just assume so.

Mott: All right, well, we gotta wrap up with our webinar this evening. Cody, I want to thank you very much for joining us tonight. Thank you for taking time and talking with us about this awesome area of research. And I also want to thank our attendees for attending the webinar. And please look for an email with a link to an evaluation survey so we can obtain your feedback about tonight’s webinar. Also, please check out the School of Pharmacy’s YouTube channel to watch the previous seven Pharmacy Experts webinars that we’ve produced for our alumni. And then in other alumni engagement activities, please look for the summer edition of DiscoverRx, which is the School of Pharmacy’s digital publication. And also please look for information from us to participate in various engagement events. We have one coming up at the Madison Mallards baseball game in July. There’s the PGA golf outing to raise scholarship funds for School of Pharmacy students also in July, and then we’ll be sending out information this summer about our alumni tailgate and viewing party that will be happening in the fall. So, everyone, that’s a wrap. Please stay safe and healthy. Have a nice evening and on Wisconsin. Good night, everybody.