10

December

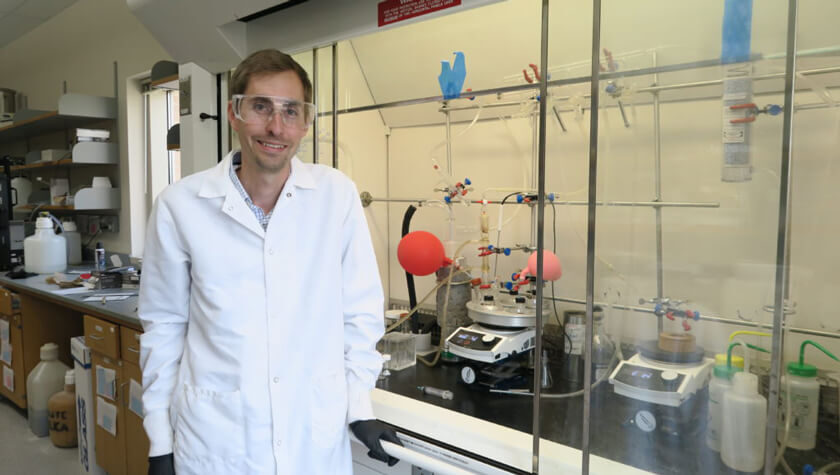

School of Pharmacy Assistant Professor Cody Wenthur and his team are shedding new light on the role of stress in psychedelic drug treatment for mental health disorders

By Nicole Sweeney Etter

For centuries, humans have used psilocybin mushrooms — commonly known as “magic mushrooms” — for their mind-altering effects. But as more evidence emerges that psychedelics could be a powerful tool to treat mental and behavioral health disorders, researchers are still trying to understand how psilocybin changes the brain to relieve anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

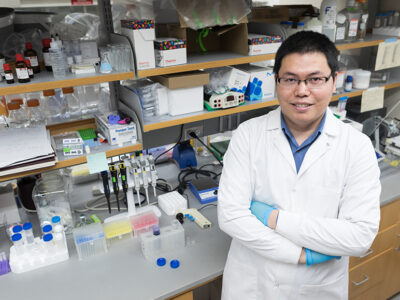

“One of the fascinating things about psychedelics as it relates to behavior is that the compounds themselves are only in your body for a matter of hours, but often the effects that are reported — the behavioral changes and changes in symptoms around psychiatric conditions — persist for weeks to months and, in extreme cases, years,” says Cody Wenthur, an assistant professor in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Pharmacy Practice and Translational Research Division.

But not everyone experiences positive effects after treatment with psilocybin. Now a research team from the Wenthur’s lab has discovered that stress could play a key role and shared their findings in ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science.

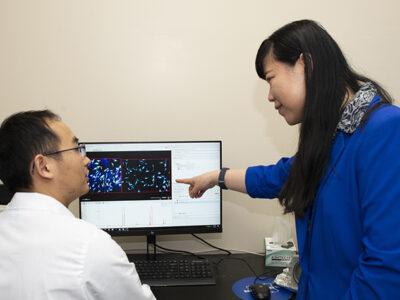

This research “presents an exciting frontier in the quest for innovative treatments for stress-related disorders,” says Nathan Jones, a UW Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology Training Program graduate student in the Wenthur Lab and lead author on the paper. “A deeper understanding of this interaction can pave the way for more targeted and effective interventions, offering hope to countless individuals struggling with conditions like PTSD and general anxiety disorder.”

The connection between stress and learning

Wenthur’s research team was curious about the role of stress in the long-term changes sometimes seen in patients after the use of psychedelic compounds.

“It’s known that when people take psychedelics, many of them will report a blissful experience that is very positive, but many also report a very challenging experience,” says Wenthur, who also serves on the executive board of the UW Transdisciplinary Center for Research in Psychoactive Substances and directs the School’s master’s program in Psychoactive Pharmaceutical Investigation. “And with increasing doses of these compounds, there is a signature in the body of activation of the sympathetic nervous system — activation of that fight or flight response — and an increase in hormones associated with stress.”

There’s substantial research on stress and its role in learning. Stressful situations can induce powerful lessons: Wenthur likens it to an ancient hunter-gatherer who learns quickly not to pick berries in a certain area after a close call with a saber-tooth tiger.

“But that’s only one part of the equation. If you have chronic stress that’s unresolved, this can actually have negative impacts on learning,” he explains. “And both of those will show up at a molecular level, too. You’ll get acute changes in the formation of synapses, where neurons are talking to one another. And you can have pruning of those synapses and loss of the integrity or complexity of the neuronal connections with chronic stress. And so the question is: Is this drug-induced stress a good thing or a bad thing?”

It’s difficult to know in humans what might drive the stress response during psilocybin use because there can be other psychological factors at play or strong cultural expectations about the psychedelic experience. That’s where animal models can be helpful: Researchers can measure their biochemical and behavioral response without the complications of pre-conceived notions that they might find in human subjects.

The impact of chronic stress

Using mice models, Wenthur’s team mapped out how long psilocybin stays in the body. They found it lingered in the system for around four hours, peaking around 15 minutes after dosing. Levels of corticosterone, a stress hormone that’s similar to cortisol in humans, followed a similar pattern.

“There was a very interesting relationship between the drug dose and the behavior that was seen,” Wenthur says. “At the highest concentration, at that 15-minute point, the mice looked anxious, and the more drug you gave, the more anxious they looked. But then in four hours, the exact opposite was true. The mice who were the most anxious at 15 minutes were the least anxious four hours later. It seemed like there was this rebound effect of reductions in anxiety.”

To tease out the effects of chronic stress, researchers gave some mice low levels of the stress hormone for three to four weeks before they were given psilocybin. “That causes downregulation of the ability of the body to release that hormone when it’s underneath a stressful condition, or in this case, when we give the drug,” Wenthur explains.

Those mice didn’t show the same reductions in anxiety-like behavior one week after being given psilocybin — in fact, their anxiety seemed worse after the psychedelic drug.

“This implies two things that are interesting,” Wenthur says. “One, not all drug-induced stress is necessarily bad at a mechanistic level. It may actually help facilitate some of these changes that are seen after the drug leaves the system. Two, if you have ongoing elevations in this stress-associated hormone that are unresolved, you have a very different type of outcome, which is more negative. We don’t want to over-interpret what this means for people, but it certainly implies that removing all stress from the experience itself may not be the ultimate goal. However, finding ways to make sure there’s resolution of any ongoing stress response seems really valuable.”

One unexpected finding: Researchers discovered that if they blocked the serotonin receptor thought to cause the altered state of consciousness — essentially blocking psilocybin’s psychedelic effect — mice still showed reductions in anxiety after psilocybin use. But that wasn’t the case when researchers blocked the receptor affected by the stress hormone.

“And so at least in this model, the stress was the relevant story,” Wenthur says.

Improving patient outcomes

Mice and humans are very different, Wenthur notes. But if the findings are translatable to humans, it could provide insights into which types of patients are more likely to benefit from psilocybin. It could also explain why psychedelic-assisted therapy has been exceptionally beneficial for patients with anxiety related to a terminal diagnosis — research has shown that about 80 percent of those patients had reductions in anxiety that persisted up through 4.5 years.

“That’s certainly an area for study: to understand whether anxiety related to an acute stressor like mortality is more responsive or more robustly and persistently addressed than ongoing stressors just related to day-to-day life,” he said.

Next, Wenthur hopes to collect saliva or blood samples from patients in psilocybin clinical trials to measure cortisol as a biomarker and get a timeline of stress response and resolution before, during and after psilocybin use. Then researchers could analyze that data compared to patient-reported outcomes on their mental and behavioral health symptoms.

“This not only broadens our scientific perspective but may also lead to more effective and even tailored therapeutic strategies for psychiatric disorders.”

—Nathan Jones

“That kind of longitudinal data would be very powerful for trying to understand who’s potentially more likely to respond in the future and what it looks like when someone is a non-responder,” he says. “How do we identify that and then hopefully get them on a different type of approach that may work better for them?”

While the recently published study focused on anxiety, the findings on the role of stress could be relevant for other conditions as well.

“A lot of psychiatric disorders have a dysregulation of stress responses and alteration of learning behavior,” he says. “So this mechanism could also be pertinent for substance abuse, mood, and depressive disorders.”

Jones, too, is excited about the potential impact of this new understanding of the stress response.

“We have identified and provided a novel and potentially critical underlying mechanism of action for psilocybin,” Jones says. “This not only broadens our scientific perspective but may also lead to more effective and even tailored therapeutic strategies for psychiatric disorders.”