By Will Cushman

This article originally appeared on UW–Madison’s news page.

University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers have recently revealed that the effectiveness of common antibiotics could depend on the neighborhood where you live. Here are the details.

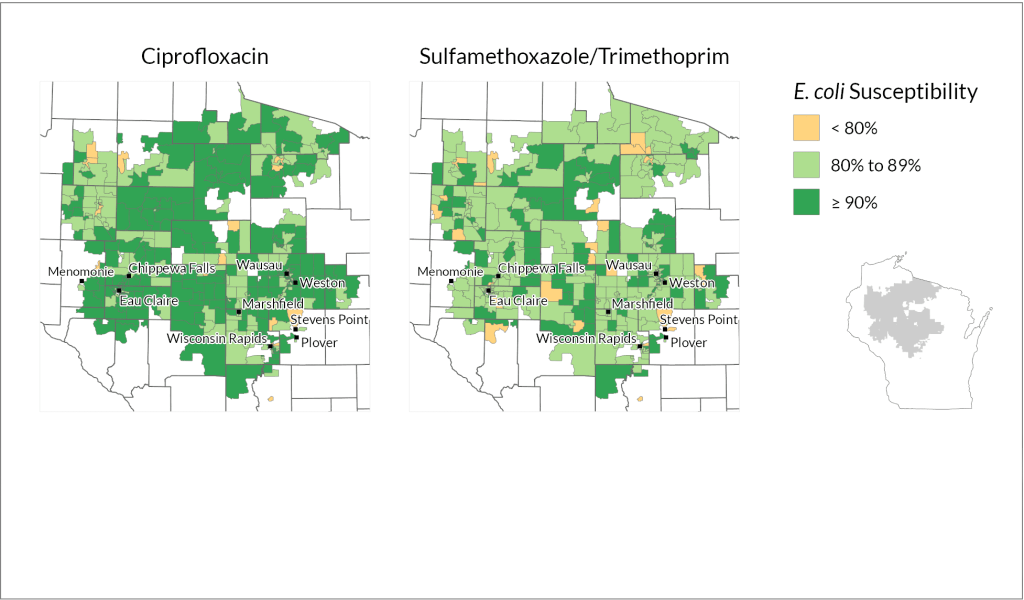

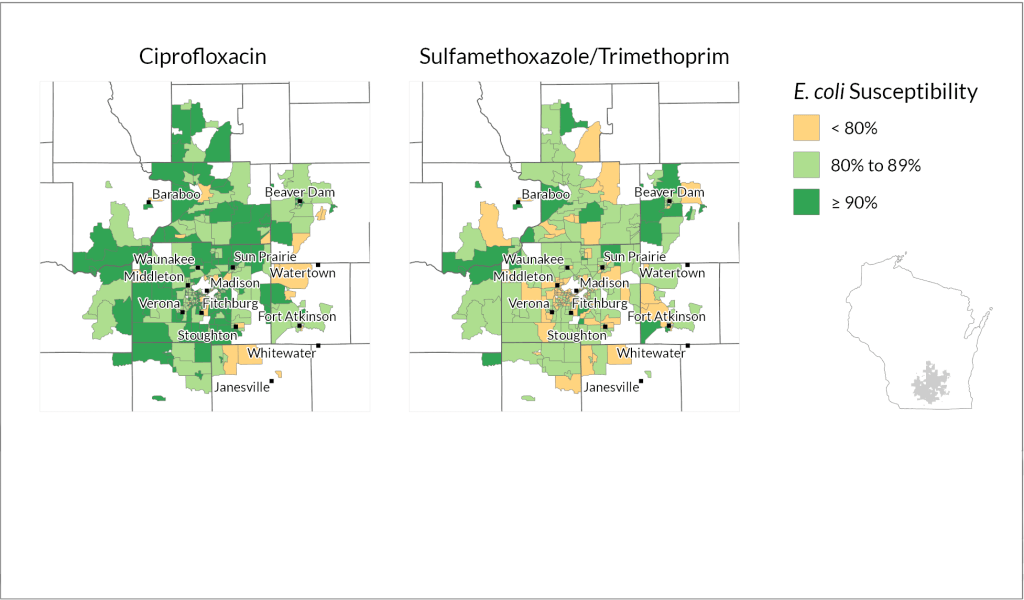

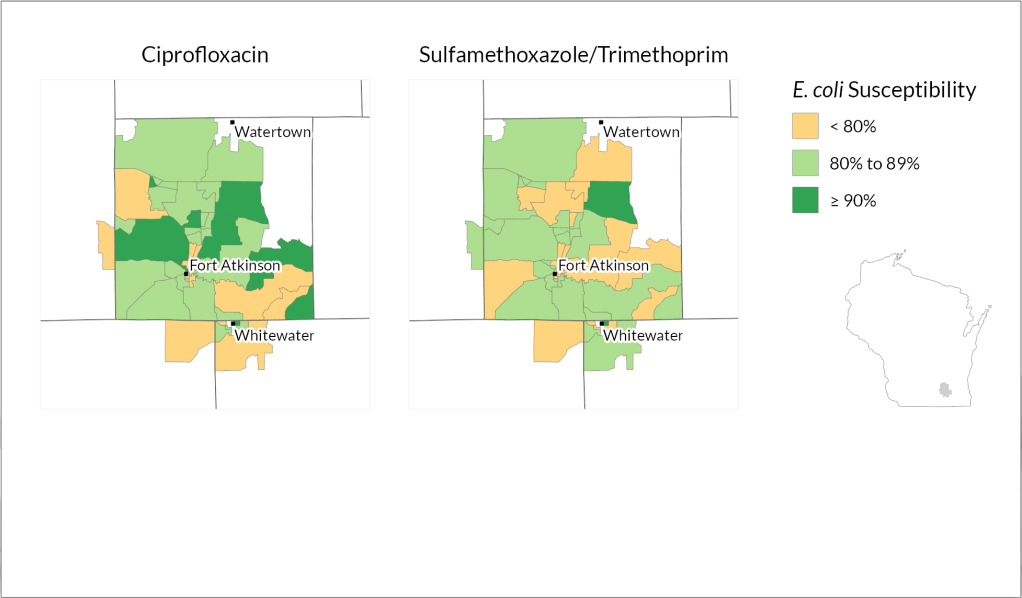

An innovative look at an old problem: Led by postdoctoral fellow Laurel Legenza, researchers at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy and State Cartographer’s Office worked with colleagues from three Wisconsin health systems to combine antibiotic resistance data from different locations throughout the state to gauge the effectiveness of a pair of common antibiotic treatments for Escherichia coli infections.

The combination of data allowed the team to identify neighborhood-level patterns in how well the antibiotics treated E. coli. They found meaningful differences between census block groups in the pathogen’s susceptibility to the two antibiotic treatments. Census block groups are a smaller unit within census tracts, each home to around 600 to 3,000 people.

The study, recently published in the journal Scientific Reports, is an innovative approach to the longstanding health care practice of tracking antibiotic resistance.

“Antibiotic resistance stats are not new, but usually they’re done at a health system level,” says Legenza. “Some large health systems may track resistance at the ICU level and compare it to the general hospital, but the data is not well understood at a community level. We took all that data and looked at where these patients live.”

What’s the big deal? Mapping variations in antibiotic resistance could help patients receive better informed treatment decisions from their health care providers, Legenza says. For instance, resistance maps could reveal neighborhoods where E. coli infections are easily treated with antibiotics with fewer side effects.

The study offers a proof-of-concept that such granular resistance mapping is possible. The research team is already planning more mapping studies and investigations into socio-economic and environmental factors that may play a role in variations.

How they did it: The researchers analyzed data from Wisconsin health systems representing rural and urban areas in different parts of the state: Fort HealthCare, Marshfield Clinic Health System and UW Health.

Marshfield Clinic spans largely rural stretches of central and northern Wisconsin but also serves mid-size cities including Eau Claire and Wausau, while UW Health encompasses the state’s second largest metro area in Dane County as well as several outlying counties. Fort HealthCare is a smaller, mostly rural health system based in Fort Atkinson, which is about halfway between Madison and Milwaukee.

Using methods that protect patient confidentiality, the researchers examined 90,000 records from patient laboratory samples where E. coli was detected and looked at whether each sample was susceptible to, or could be treated by, common antibiotics: ciprofloxacin and a combination of sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim.

They found variations in the bacterium’s susceptibility to each treatment within both urban and rural parts of all three health systems.

“What the data clearly shows is that resistance patterns are potentially different in different neighborhoods,” says Legenza.

Further, Legenza and her colleagues were able to identify specific census tracts as “cold spots” or “hot spots” of susceptibility.

A little more background: Antimicrobial resistance is a growing public health threat in the United States and globally. As certain bacteria and fungi gain the ability to evade drugs designed to treat them, patients face a growing risk of infections that are difficult to treat. More than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur in the U.S. each year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and more than 35,000 people die annually as a result.

Prior research has shown geographic variations in antimicrobial resistance, but few studies have mapped resistance patterns in the U.S., and none with as much granular detail as this new report. The neighborhood-level maps build on a previous study Legenza led that mapped antibiotic resistance patterns in Wisconsin at a broader level.