School of Pharmacy alums trace the history, and present, of one of the nation’s first pharmacy co-ops

By Jessica Steinhoff

Peppered with condominiums, bubble-tea shops, and a growing fleet of electric cars, the Madison, Wis., of today looks quite different from the Madison of the early 1970s. Though the sights and sounds have evolved with the times, modern-day Madison owes a great deal to this period of experimentation and social change.

The civil rights movement led many ’60s Badgers to reconsider what a just and truly democratic society might look like, a question that gained urgency as the Vietnam War turned the world upside down. Community-based cooperatives eager to answer this question mushroomed during the early ’70s, but not many survived more than a few years. A notable exception is Madison’s Community Pharmacy.

One of the nation’s first pharmacy co-ops, Community Pharmacy was co-founded by a University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy alum and has since employed hundreds of Pharmacy Badgers during its 50-year history. In addition to filling prescriptions and selling over-the-counter medications, the shop is known for its expertise on vitamins, supplements, herbs, and homeopathic remedies, its extensive selection of these products, and its compassionate response to public health crises.

Candid conversations with customers are also an essential part of Community Pharmacy’s approach to wellness, according to Aimee Speers (PharmD ’05). She’s had scores of them in her five years as the chief pharmacist.

“Whether someone is coming in for a refill, a new prescription or an answer, I see if they’ll open up about what’s going on with their health,” she says. “Being able to counsel them is one of the best parts of the job. It helps me build relationships and keep them strong, and I truly believe that’s what sets us apart from other pharmacies.”

Seeking alternatives

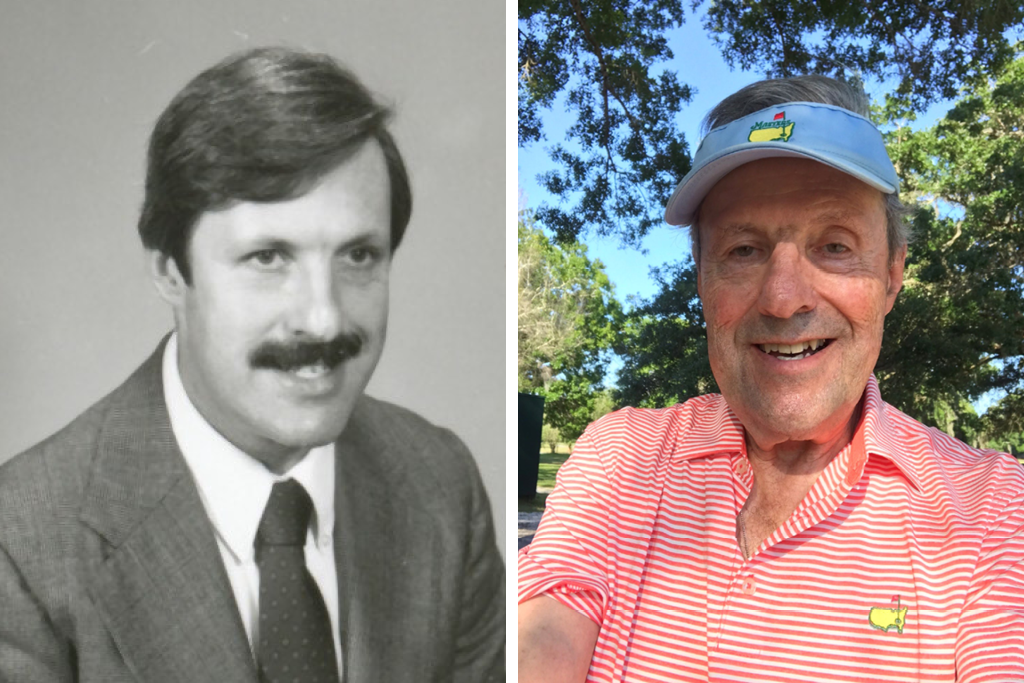

Community Pharmacy’s origin story begins on the UW–Madison campus of the early 1970s, where Bruce Stein (BS ’59, MS ’67, PhD ’70) was pursuing a doctorate in pharmaceutical biochemistry. To make ends meet, he worked part time at local drugstores, filling in for staff pharmacists who needed the day off. When classmates learned of this gig, they asked him to fill their prescriptions — and give them a student discount.

Before long, Stein was flooded with these requests. That’s when the Wisconsin Student Association (WSA) approached him with a proposal: adding a student-run pharmacy to the campus store where they sold books, records, and snacks.

“I liked the idea of having a pharmacy service for students and told them they’d need at least one licensed pharmacist,” Stein recalls.

Stein helped the WSA launch the pharmacy and hired its first full-time pharmacist, Peter Kiesch (BS ’70), in 1972. He also worked there part time while in law school, then moved away in 1973 to start his career as a patent attorney. According to Kiesch, who passed away in 2016, the WSA wanted to give students an alternative to a local chain that owned all of the campus-area pharmacies.

“Institutions were suspect to most people on the left in Madison,” Kiesch remarked in a 1992 interview for the UW–Madison Oral History Program. As a result, many weren’t comfortable with drugstore chains.

The WSA figured that buying medications in bulk could keep costs down, and that most of the savings could be passed along to students.

Fueled by this vision, about 60 volunteers spent a year fundraising and setting up the pharmacy. Campus newspaper The Daily Cardinal provided an $8,000 loan, and students purchased $1 bonds sold in front of Memorial Library, adding more than $5,000 to the pot.

“My first encounter with Community Pharmacy was with those students selling bonds,” says David LaLuzerne (BS ’72), who worked there from 1974 to 1989. “I was a student at the School of Pharmacy then, it was the height of the Vietnam War, and it seemed like they were creating the kind of place I’d want to spend my time.”

It was also the kind of place many students wanted to shop. According to Kiesch, business was brisk when the store opened at 511 N. Lake St. in September 1972. Though it was tucked beside an alley, in the shadow of a larger drugstore, it quickly became a destination.

Gaining credibility

Community Pharmacy’s alley-adjacent location spawned some memorable advertising copy, LaLuzerne says. His favorite was a newspaper ad that read “Remember when you could buy drugs in an alley? You still can!”

This tongue-in-cheek message nodded to assumptions early critics made about the staff. According to Kiesch, some regulatory bodies viewed the workers as “hippies that were going to sell drugs to anybody that wanted them,” and soon a local newspaper article asked readers if Community Pharmacy could be trusted.

“We had to come out and say, ‘We’re not going to do that, we have to obey the law,’” he said in his Oral History Program interview.

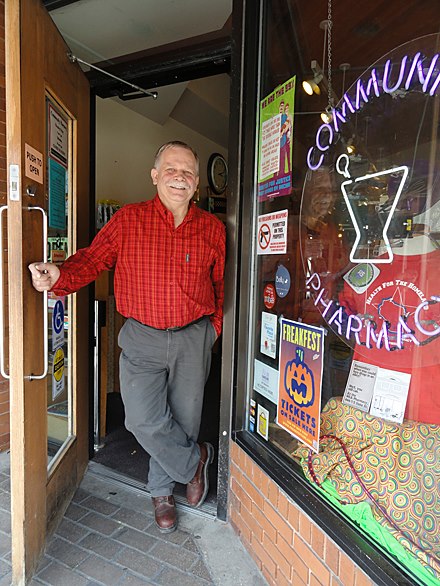

Longtime chief pharmacist Richard Kilmer (BS ’74) says that the examining board visited often in the early days.

“We earned their respect quickly because we followed the rules very closely,” he recalls.

LaLuzerne — who served on Madison’s Public Health Commission for two years, including one as chair — remembers how Community Pharmacy went above and beyond to prove its legitimacy to the entire community. One example is a phone chain workers created to alert all Dane County pharmacies about forged prescriptions.

“If we suspected something illegal like that, we’d call two pharmacies on the list and then the next place would call two more and so on,” he says. “I think it endeared us to the community.”

Community Pharmacy also became an important training ground for the School’s student pharmacists and a launching pad for ambitious professionals.

LaLuzerne, for instance, started Green Earth, a purveyor of health foods and herbal products that had three Madison locations during its heyday. In addition to working at Community Pharmacy from 1984 to 2021, Kilmer represented Madison’s southwest side on the Dane County Board from 2016 to 2020. As a board supervisor, he served on the Equal Opportunities Commission and the Health and Human Needs Committee, among others. He has also been a major player at local AIDS organizations and helmed the board of Madison’s OutReach LGBTQ center.

Growing pains

One day a fence appeared in the alley, in front of Community Pharmacy’s lone entrance. The workers scrambled for solutions. Realizing the building could be accessed from State Street, they cut a hole in the wall and added a staircase to create an alternative entrance.

“We did that as a group in one weekend,” Kiesch told the Oral History Project. The immediate problem was solved, but the stressful project created a bigger issue: persistent tension within the organization.

Things came to a head in 1976 with the pharmacy becoming a worker collective and splitting from the WSA. Before this, it had a corporate structure, including a board of directors with WSA representatives.

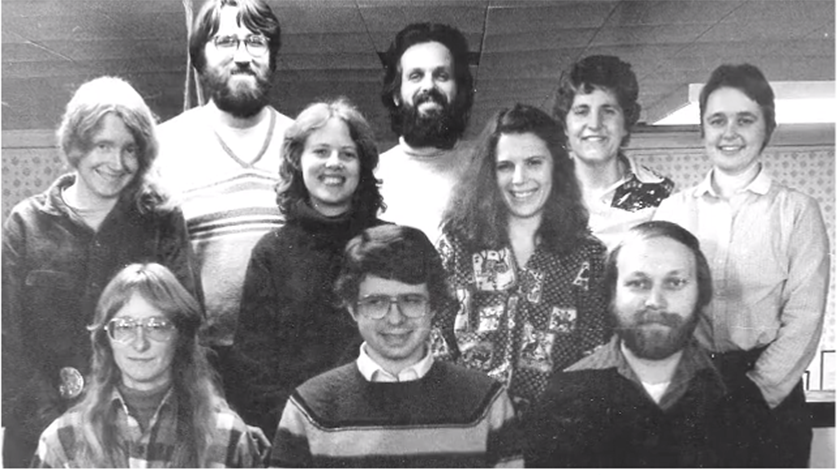

The collective structure worked well when business started booming and there were about 10 employees, according to Kiesch, but that growth created a need for more space and staff. That’s when the drawbacks of their collective decision-making became painfully apparent. Something had to change.

But first the business had to endure another change: moving to 341 State St., which was more expensive than the previous location and farther from the UW campus. Chain pharmacies were expanding and HMOs, a new player on the health care landscape, were opening pharmacies left and right. To stay in the black, the business evolved.

That’s when alternative therapies entered the picture.

“Peter was very involved in homeopathy, so he suggested we branch out into that, along with herbs, vitamins, and supplements,” Kilmer says. “These became a big part of the business and he was very knowledgeable about them. At the same time, he knew his limits and was great about making referrals when there seemed to be something more serious going on with a patient.”

In Kiesch’s view, alternative health products sustained the business during lean times and offered opportunities for further growth. He deepened his homeopathy expertise as LaLuzerne expanded his herbal knowledge.

“When I was in pharmacy school, I took a course in pharmacognosy and became very interested in the plants drugs come from,” LaLuzerne says. “I don’t see herbs so much as medicine but as a means of maintaining good health.”

Community Pharmacy soon became a trusted resource for learning about drug interactions, especially interactions between traditional and alternative medicines.

“To this day, doctors and other pharmacists call us for help advising patients who need a new prescription and are already using herbal or homeopathic remedies,” current pharmacist Speers says.

By 1989, LaLuzerne’s last year at Community Pharmacy, sales of alternative health products comprised more than half of the business. One of the factors that spurred his departure led the pharmacy to become a worker-run cooperative in 1991.

“We needed a consensus to make decisions, and sometimes that was hard to achieve, especially as we hired more employees,” LaLuzerne says. “Our meetings sometimes went until 2 a.m., which just isn’t for everybody.”

After several years of exploring different business models, the staff settled on a team approach. Instead of having owners or managers, each employee belongs to a team dedicated to a particular area of the business, such as accounting or merchandising. Smaller decisions are left to the teams, while the bigger ones are open to all employees.

Some of the biggest decisions in recent years have involved location. Community Wellness Shop, a second location focused on alternative remedies, opened in Middleton in 2015. And in August 2021, the shop traded State Street for Fair Oaks Avenue on Madison’s near-east side.

The pharmacy’s mission has stayed the same, Speers notes.

“The purpose of the pharmacy has always been providing affordable medication to the community, starting with UW students 50 years ago,” she says.

Pushing the envelope

From the outset, Community Pharmacy has challenged people to think about health in new ways. Encouraging customers to go generic was one way they did this in the ’70s.

“We were one of the first places in Madison — and probably the country — that was heavily into generic prescriptions and over-the-counter generics, which many people looked down on at the time,” LaLuzerne says.

Packaging these drugs helped the young pharmacy save money, much of which was donated to community causes.

“For a while, almost anyone who wanted a donation got one,” Kilmer says, noting how the pharmacy gifted funds to AIDS agencies, community radio station WORT-FM, and other groups that shared their commitment to public service. The pharmacy also provided low-cost medication to under-resourced clinics in both Madison and Central America.

Unlike most drugstores of the era, Community Pharmacy chose not to sell cigarettes out of a commitment to public wellness. And they offered some products their competitors didn’t have.

For instance, birth-control pills were one of Community Pharmacy’s biggest sellers in the early ’70s.

“Nearly every female college student in Madison was on birth control, so making it more accessible and affordable was a big deal,” Kilmer says.

The pharmacy started distributing handbooks on birth control and sexually transmitted diseases in 1973 and sold condoms to anyone who wanted them when a state law restricting them to married couples lingered on the books.

“We were taking a risk before the law changed, but we knew we were saving lives,” Kilmer explains.

Kilmer made AIDS prevention a personal mission, helping many patients learn how to lower their risk of contracting it. Countering misinformation was crucial for protecting people and minimizing stigma.

“During the early years of the AIDS crisis, sometimes I attended two or three funerals a week for patients and friends who died of AIDS,” he says. “At the pharmacy, we provided a lot of education about safer sex, as well as AIDS treatment and research. We were also instrumental in providing free, clean needles [to drug users] when hardly anyone was doing that.”

A similar ethic has driven Community Pharmacy’s opioid-crisis response. It was likely the first pharmacy in Wisconsin to dispense no-cost naloxone for overdose reversal, Kilmer says. To help prevent overdose, it also offers fentanyl test strips through a partnership with Public Health Madison Dane County.

“Everyone deserves health care, and no one should have to go bankrupt to get compassionate health care. That’s what this pharmacy was founded on, and it’s part of what has brought one amazing person after another to our staff.”

—Richard Kilmer

“We provide naloxone and [fentanyl] test strips for free, no questions asked, but will counsel anyone who is willing to discuss their opioid use,” Speers says. “Harm reduction is important, and it makes a positive impact on public health. It’s especially important in our community right now as we’ve seen opioid-overdose numbers increasing during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Even when much of the city shut down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Community Pharmacy staff made sure people could get their prescriptions.

“We did a lot to remain open, especially at the beginning of the pandemic,” Kilmer says. “And we hand-delivered medication to many people who were afraid to go out.”

As COVID-19 pummeled many of society’s most vulnerable, staff urged community members to take care of each other and take advantage of the pharmacy’s resources.

“If you or someone you know is struggling in the current economic system, please reach out,” an August 2020 Facebook post announced. “We have resources (for very little to no cost) and we are here to give them to those who need care and a community.”

One such resource is Wisconsin’s drug repository program, where Community Pharmacy and other facilities collect unused medicine and donate it to patients who need it but can’t afford it.

“Recently, there has been a surge in the number of people using the repository program, probably because of hardships related to the pandemic,” Speers says. “We feel fortunate that we can help improve medication access for some of the area’s most vulnerable patients by participating in this.”

Kilmer says providing a caring community to those who need it is equally important, if not more so.

“Everyone deserves health care, and no one should have to go bankrupt to get compassionate health care,” he says. “That’s what this pharmacy was founded on, and it’s part of what has brought one amazing person after another to our staff.”