Taiwan welcomed two School of Pharmacy faculty to share their expertise and build partnerships

By Katie Gerhards

The practice of pharmacy looks different in hospitals than it does in community pharmacies and clinics, and there are more variations by health system. It’s a diverse and evolving field in the United States, and the possibilities seem even more endless when we look beyond national borders and across oceans.

In Taiwan, for example, pharmacists are fully plugged in to their patients’ health histories—prescriptions filled anywhere in the country, diagnoses, hospitalizations, and lab values from the last three months are all available to pharmacists via a Pharma Card carried by each patient, like a drivers’ license.

“I think there’s a perception that pharmacy is behind in Taiwan, but there are some things in their national health system that are much further ahead than we are,” says Michelle Chui, associate professor and vice chair in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Social and Administrative Sciences (SAS) Division.

Chui and Assistant Professor Olayinka Shiyanbola, also in SAS, were each personally invited to Taiwan to share their renowned expertise in health literacy, medication safety, and the importance of research with graduate students, faculty, and other health professionals at some of the country’s leading universities and conferences, and to learn more about how pharmacists operate abroad.

Sharing expertise abroad

Shiyanbola was invited by Hsiang-Wen (Margaret) Lin, associate dean and associate professor at the China Medical University (CMU) School of Pharmacy in Taichung, Taiwan, to speak at the 2018 International Asia Health Literacy Conference in October about health literacy and medication use.

Lin and Shiyanbola met through one of Shiyanbola’s graduate students, Yen-Ming Huang, who is also Taiwanese, and connected over their shared research interests. Shiyanbola examines patient perceptions and their role in medication use and adherence, and Lin developed a health literacy scale to assess patient outcomes.

Health literacy is an important and oft-discussed topic, but not many—other than Shiyanbola—are looking at how it can be applied in pharmacy health services research, so Lin felt that her uncommon area of focus would make an excellent addition to the conference.

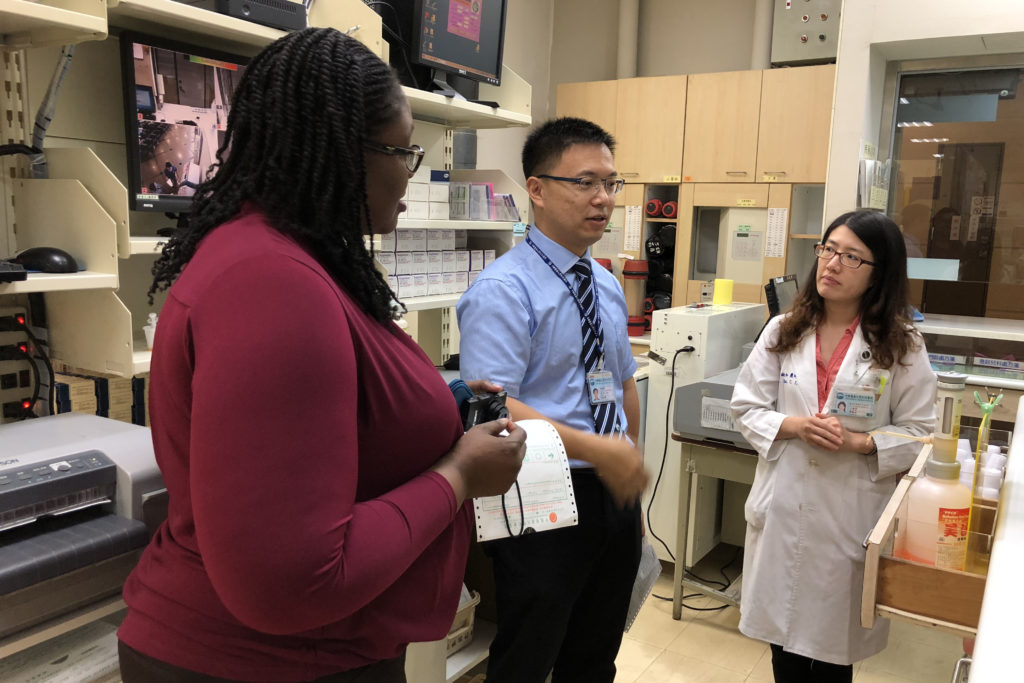

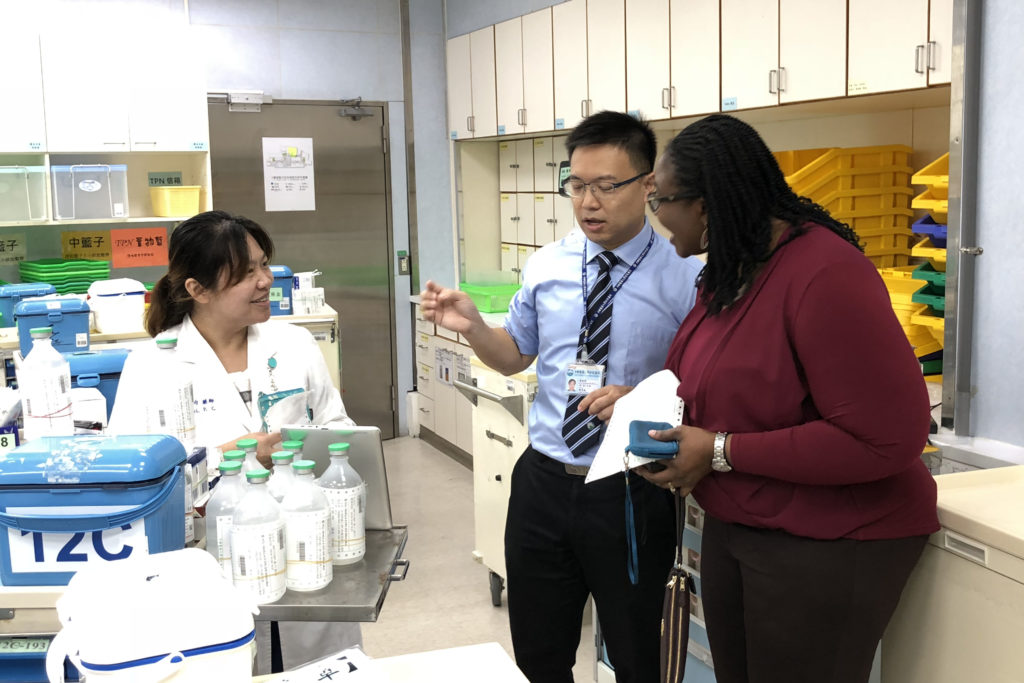

Her appearance at the health literacy conference soon snowballed into more meetings and presentations at CMU as well as Taipei Medical University (TMU), where Shiyanbola spoke about the importance of health literacy in designing adherence interventions and met with graduate students for an open discussion about research. At CMU, Shiyanbola held a class on psychosocial factors influencing medication adherence and a separate class about applying mixed methods research in pharmacy and health services research.

“Mixed methods research is gaining a lot of ground in medicine, sociology, education, public health, and pharmacy,” she says. In 2015, she was accepted by the National Institutes of Health as a scholar in the new Mixed Methods Research Training Program for the Health Sciences—one of 14 health professionals nationwide selected for the program’s first year. She underwent a year of training in the collection, analysis, and integration of quantitative and qualitative data that enable a greater understanding of research problems and processes. To bring that knowledge back to the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy, she introduced a new mixed methods course in the Social and Administrative Sciences in Pharmacy graduate program. Someone at CMU had read about her unique training and set up the class to hear more.

“As a junior faculty member, it feels great to have already established a niche in the research world, especially among international peers,” says Shiyanbola. “It makes me realize that what I’m doing is making a difference.”

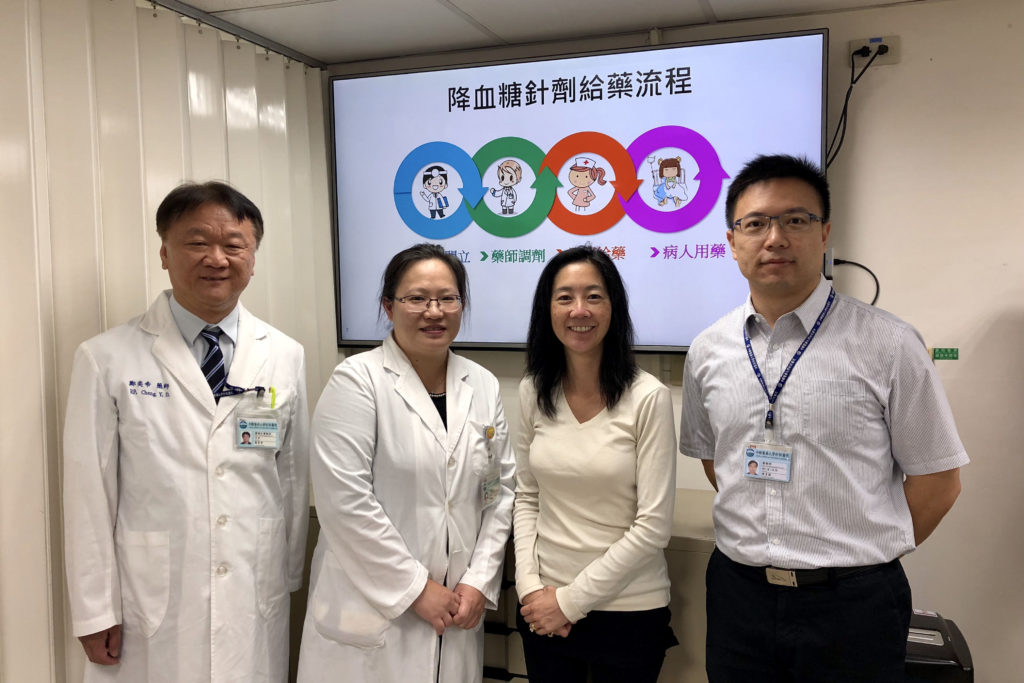

On Shiyanbola’s first day in Taiwan, she toured China Medical University Hospital with a fellow Badger pharmacist: Yu Chieh (Jack) Chen (PhD ’11), now director of clinical pharmacy services at the hospital.

On the tour, she got an inside look at how they incorporate Chinese medicine into their pharmacy services. “That is not something I was trained in or have seen a lot of, so it was interesting to see how they were boiling and packaging the herbs together,” she says.

As a graduate student at the School of Pharmacy, Chen had taken classes with Chui and remembered her area of expertise. “Dr. Chui has a research interest in using human factors to study medication safety in a community pharmacy setting,” Chen says. “This is a unique area that not many pharmacy researchers in Taiwan are involved in.”

So he invited Chui to Taiwan in November to speak at two conferences—one for pharmacy administrators, where she discussed how to encourage pharmacy students to become researchers and build research into the curriculum, and another for health-system pharmacists, where the topic was how to get staff pharmacists to conduct and publish research. While in Taiwan, she also held presentations for graduate students at CMU and Taipei Medical University about her research and how she integrates engineering principles to study medication safety strategies and issues in pharmacy.

“Her talks inspired many people and received overwhelmingly positive responses,” says Chen.

In her last presentation, for a local professional organization of community pharmacists, she discussed some of the key similarities and differences in how pharmacy is practiced in the U.S. and Taiwan.

“I’d spent a week touring pharmacies and interacting with pharmacists, so I felt like I had a good lay of the land for what community pharmacy looks like in Taiwan,” Chui says. “It was nice to be able to articulate some of those differences.”

Gaining international pharmacy insights

The largest difference Chui noted is the presence of a national health insurance, which is what makes the Pharma Card possible. “Access to complete patient information provides opportunities to avoid therapeutic duplications and to truly address potential drug-drug interactions that we can’t do here in the U.S. because of the limited information pharmacists have,” says Chui.

Despite having access to patient information, pharmacists in Taiwan aren’t really talking about medication therapy management, disease state management, or medication safety principles.

“They’re building relationships so that they can send their pharmacists and graduate students here to see what the standard of practice is so that they can then go back to Taiwan and be the champions for change in their practice environments,” says Chui.

Through the national health insurance, patients have easy access to health care providers and they pay almost nothing for their medications—but, interestingly, Taiwan nonetheless struggles with medication adherence.

“In the U.S., a lot of patients don’t take their medicines for reasons other than access issues, and that is where my research comes in to see what is going on in the mind of the patient,” says Shiyanbola. “In Taiwan, they have a similar problem where people are using the available health care services and are picking up their medications but aren’t taking them.”

Overuse of the health care system leads to the risk of physicians and pharmacists alike being overworked, but some Taiwanese pharmacies have implemented policies to try to offset that risk.

The community pharmacies Shiyanbola visited staffed three pharmacists during the same hours, because each pharmacist has a cap of 80 prescriptions per shift.

Working together for a lasting impact

Both Chui and Shiyanbola left Taiwan with a greater sense of what pharmacy can look like and how it affects patient health. And they both have found some points for potential collaborations to strengthen the relationship between the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy and Taiwan’s leading health care educators.

“UW–Madison School of Pharmacy has given me maturity in facing challenges in academia and clinical practice,” says Chen. “Most importantly, the School has taught me the integrity that is cherished by pharmacists and researchers.” China Medical University is eager to develop a partnership with the School of Pharmacy, he says, which could include research collaborations or a summer exchange program for pharmacy students.

Shiyanbola and Associate Professor Denise Walbrandt Pigarelli, in the School’s Pharmacy Practice Division, developed an intervention to tailor pharmacist counseling to each patient’s level of health literacy and self-efficacy. When patients come in to the pharmacy, they fill out a survey to gather information about their health literacy, self-efficacy, and beliefs about medicines and illness, and then it is scored and shared with the pharmacist, who then knows what to focus on during the consultation.

Lin is interested in implementing that intervention at China Medical University Hospital and is still in talks with Shiyanbola about which components would be most effective for their unique challenges.

Chui, too, will likely be leaving an imprint at CMU. “We talked about the School of Pharmacy’s medication safety course and what the goals of the class are,” says Chui. Taiwanese pharmacy curriculums don’t include medication safety principles, so even by adding a small amount of some foundational material, student pharmacists would have a sense of what to watch for and what to learn after graduation. Chui is working with faculty there to explore ways to share and implement pieces of her medication safety course.

“This international collaboration wouldn’t have been possible without the quality of the research and reputation of the School,” says Shiyanbola. “The reputation precedes the institution—everyone knows the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy, and we’re grateful for the opportunity to build genuine partnerships.”

Learn more about Associate Professor Michelle Chui’s work in the newly relaunched Sonderegger Research Center for Improved Medication Outcomes.

Read about Assistant Professor Olayinka Shiyanbola’s research and patient-centered care.