28

March

Student pharmacists develop industry knowledge, entrepreneurial and leadership skills

By Katie Ginder-Vogel

Your pharmaceutical startup just discovered a new molecular entity (NME) with the potential to treat Type 2 diabetes and obesity, and the preclinical data is promising enough that your company is moving forward with human clinical trials in order to gain regulatory approval and bring the NME to patients.

How will your company ensure that this innovative therapy makes it to market and into the hands of patients?

That was the challenge set forth in this year’s second annual Value of Industry Pharmacists (VIP) Case Competition, in which pharmacy students around the country compete to design the best development plan to bring a theoretical drug to market. More than 30 teams are competing this year, including the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy, which is entering for the first time. The School of Pharmacy team of 25 students includes 24 students in the PharmD program from every class, DPH-1 through DPH-4, plus one Pharm-Tox undergraduate student.

The competition challenges student chapters of the Industry Pharmacists Organization (IPhO) to demonstrate their knowledge of the pharmaceutical industry and explore the commercial functions involved in designing a drug development plan, from concept to approval and commercialization.

In addition, the competition asks student pharmacists to dive deep into real-world pharmacists’ roles and responsibilities throughout the industry with the overarching theme of understanding the value of industry pharmacists.

“A PharmD degree is a virtually limitless degree that can lead to fulfilling careers in any area of the health care sector, especially in industry.”

–Dean Bowen

“This competition showed us that our pharmacy education does not limit us to a community or hospital role, but rather, that a PharmD degree is a virtually limitless degree that can lead to fulfilling careers in any area of the health care sector, especially in industry,” says Dean Bowen, a second-year PharmD student and Industry Pharmacists Organization (IPhO) student chapter president, who led the UW–Madison team throughout the competition and also oversaw the marketing subteam with Tessa Burghardt, DPH-2.

“A pharmacist pursuing a career in industry has the ability to affect patient care on a global scale by helping bring new therapies to market,” adds Bowen.

The winning chapter gets $1,000 and recognition at the 2018 IPhO Annual National Meeting.

“I would consider the competition to be an excellent learning experience, regardless of outcome,” says Nick Friedlander, DPH-2. “It was intriguing to see the entire process involved in bringing a drug to market, and it was rewarding to see our project come together over time.”

Teaming up to create a drug development plan

The 25-student UW–Madison School of Pharmacy team broke into smaller groups focused on each commercial function involved in designing a drug development plan: clinical development, regulatory affairs, medical affairs, and commercial strategies (marketing). They had to submit their 13-page comprehensive drug development plan in November 2017. Then, in February 2018, the team made their final submission of a 35-minute PowerPoint presentation video that covered all components of their drug development plan, as well as an added challenge point.

This year’s extra challenge required teams to submit a Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR) plan that included key activities and studies that should be implemented pre- or post-drug launch. HEOR plans were also expected to include real-world evidence that supports the additional value of the hypothetical drug, such as cost savings and patient- and provider-focused evidence, as well as hypothetical collaborators.

“This competition has been an invaluable bridge in connecting us to the actual roles of pharmacists in different areas of industry,” says Tessa Burghardt, marketing subteam co-lead.

“Not only did we have the option to dive deeper into specific areas within industry, but we could also see the ins and outs of other fields, by collaborating with other students working on different functional areas.”

“Our students are the best!” says second-year PharmD student (DPH-2) Graham Edwardson. “Everyone learned a lot, put in a lot of hard work, and had fun. I really wanted to come into this and learn more about industry and what all the companies out there are doing on a daily basis.”

Each team was paired with an industry fellow who provided advice and guidance; the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy team worked with Kory Gardner, a PharmD Marketing Fellow at Novocure, Inc.

Learning the drug development process

Each subteam (Clinical Development, Regulatory Affairs, Medical Affairs, Marketing, and HEOR) specialized in understanding and exploiting one aspect of the process of researching, developing, and marketing a new hypothetical drug.

“I believe the team members learned a lot about the roles available in industry and the process that each functional area like clinical development needs to follow to bring a drug to market,” says Bowen.

Burghardt says the competition exposed the student pharmacists to numerous career paths available within the pharmaceutical industry.

“Sure, you can research all of the different career paths and talk to people who hold different roles you might be interested in, but you never truly grasp what it’s like to have one of these positions until you’re immersed in the responsibilities,” she says.

The clinical development group: Emphasizing safety and efficacy

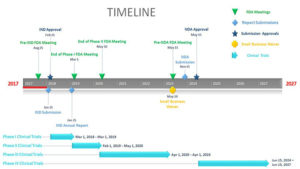

Given the rigor of the process, drug development can take more than 10 years for certain drugs. The competition required teams to design a high-level clinical development plan that supports their drug candidate through all four phases of clinical trials.

“The clinical development stage has a lot going into it, and it was fascinating to learn about the rules and regulations going into this process,” says clinical development subteam leader Bernie Brooks, DPH-2. “Being focused on the clinical development portion of the competition made me appreciate the amount of hard work that goes into validating the safety and efficacy of a drug.”

Teams were asked to address the primary indication for which they were seeking U.S. regulatory approval, detail their clinical trials, objectives, patient population and timeline; anticipate and address potential difficulties in the development process; and address how pharmacists’ education and clinical experience could contribute to their success as clinical scientists. Teams were expected to include appropriate safety and efficacy data to support approval from health authorities.

“Success in clinical research and development portions of the drug process relies heavily on reading through literature to continually stay up to date on what other companies are doing, where a promising avenue of development lies, and what research has been done already,” says Brooks. “You must also be an intellectual leader and entrepreneur. Pharmacy school provides us with opportunities through academia, rotations, organizations, and meetings that will advance our skills to become exceptional pharmacists in industry.”

Brooks says it was challenging to come up with drug development ideas that would set UW–Madison apart from the other teams, while keeping their ideas feasible and realistic.

“We did a lot of research to make sure the clinical development trials were plausible and not too sci-fi,” he says. “Our training in pharmacodynamics (the effects of drugs on the body) and pharmacokinetics (the effects of the body on drugs) helped us come up with a plan for how we wanted our drug to be formulated, dosed, and administered. Other courses, such as biochemistry and medicinal chemistry, also helped in the drug development plan.”

Nick Friedlander, a member of Brooks’ clinical development subteam, who also helped the HEOR group, says he learned that one of the primary challenges in clinical development is appropriately balancing the internal and external validity of the clinical trials.

“Choice of relevant and appropriate comparator product and design choices related to blinding were additional challenges we faced over the course of our clinical trial protocol development,” Friedlander adds.

Friedlander says the competition taught him about the various types of clinical trials and the challenges associated with their interconnected timelines.

“Learning about the intricacies involved in this complex process has been eye-opening and has given me a huge appreciation for the massive collective effort required to earn FDA approval,” he says.

The clinical development subteam relied on the skills they learned in their drug delivery systems course to design their product’s delivery mechanism.

“We also used knowledge from our pharmacotherapy courses to determine the appropriate resources to validate the selection of comparators and endpoints,” says Friedlander. “Overall, the competition has helped me to build a more complete understanding of clinical trial design and has allowed me to more clearly understand the potential roles for industry pharmacists.”

Regulatory affairs: Developing a regulatory strategy to achieve FDA approval

Typically, the regulatory affairs team in a company would prepare all of the necessary documentation and applications for the FDA, in order to get approval to study a drug in clinical trials and then market it to the public.

The regulatory affairs student subteam developed a U.S.-focused regulatory strategy that they believed could be approved by the FDA and also lead to faster drug development and drug differentiation. The group came up with an Investigational New Drug (IND) filing strategy, with internal filing timelines, from summary document drafting to IND submission to IND clearance.

The team also had to agree upon the key messages of the IND package; decide how and when they would use health authority (FDA) interactions; and decide whether they would utilize any expedited programs. The group had to describe which pivotal and supportive trials would be used to support approval, with timelines, and write about pharmacists’ advantages in regulatory affairs roles, compared to other regulatory affairs professionals.

“I have found that collaboration and teamwork are both huge staples of the regulatory role, as well,” says second-year PharmD student Griffin Budde, who led the regulatory affairs subteam. “Consistently practicing our ability to communicate and present new ideas within a professional group gives us, as future pharmacists, an advantage in a regulatory role.”

Medical affairs: Identifying and connecting with stakeholders

The medical affairs subteam came up with evidence-based information regarding their hypothetical drug, both pre- and post-launch, to optimize product utilization. They researched and identified the diabetic care experts who were leading clinical trials or changing how diabetic care is practiced in the U.S., and included their names in the report. They came up with a hypothetical plan for how their “company” would disseminate medical information to external stakeholders and train internal stakeholders, including who could receive off-label information about the drug and when during the drug development process the “company” should consult Medical Affairs.

They also explained the value of having a pharmacist on the Medical Affairs team.

“The Medical Affairs team is involved with publications, communicating with key opinion leaders, demonstrating the efficacy of the drug, and providing information about the company’s product to internal and external stakeholders,” explains medical affairs subteam leader Greg Norsten, DPH-2. “Pharmacists are integral in this setting, due to their expertise and training.”

Norsten says that the pharmacology and pharmacotherapy courses student pharmacists take provide them with the knowledge to communicate with other medical professionals in a medical affairs role.

“In order to communicate with key opinion leaders and to publish papers, you have to understand disease states and the medications that a firm is developing,” says Norsten. “These courses, that are continued throughout our pharmacy education, along with communications lab in our third year, are relevant to medical affairs.”

The case competition allows student pharmacists to apply their pharmaceutical knowledge in a new context.

“The case competition gives us the opportunity to take what we’ve learned in class and apply it in the context of the pharmaceutical industry,” says Norsten. “The aspect of this competition that I found most interesting probably would be having the ability to see what it is like to work in an industrial setting while still in pharmacy school.”

Marketing: Creating the commercialization plan

The marketing subteam created the commercial strategy that would set their imaginary drug apart, highlighting the brand’s benefits and setting their product up for strong sales. They described the competitive landscape, conducted market research, developed a brand strategy, and identified their target audience.

“I’ve been learning specific marketing techniques, such as identifying and creating core messages,” explains Bowen. “I’ve learned to understand customers’—patients, providers, and payers—needs, and I’ve learned how to develop a product positioning statement.”

The marketing team had to include all of those elements—a product positioning statement; core messages that communicated the clinical trials results, the brand’s competitive advantage; the company’s mission and values; and a comprehensive marketing strategy. They also had to think about how industry pharmacists add value to marketing teams.

“I’m really proud of our team’s motivation and performance throughout this whole competition.” –Tessa Burghardt

“Pharmacists are medication experts who understand the current medications that are on the market, what therapeutic gaps exist, and how new therapies address therapeutic gaps,” says Bowen. “Having a pharmacist on the marketing team is vital to effectively identify the target market for a new therapy and to know how best to promote the medication to patients, payers, and prescribers.”

Burghardt says the marketing subteam used information they learned in their drug delivery systems course to highlight the unique advantages of their drug’s delivery system.

“Our clinical development team designed our drug as an oral nanoparticle, which differed dramatically from other currently available GLP-1 agonists, since they are typically injectables, so we applied knowledge from the course to highlight the unique advantages of this delivery system in our marketing materials,” says Burghardt. “We also used a lot of concepts from Dr. David Mott’s managing pharmacy systems course when dealing with fiscal aspects of the marketing process.”

An added challenge: Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR)

HEOR was a new topic for the student pharmacists on the UW–Madison case competition team, presenting an added challenge. Graham Edwardson, who led the subteam, had always been interested in HEOR and has a background in economics, having earned a BS in economics and a BS in biology from UW–Stevens Point before beginning pharmacy school. Edwardson also took a health economics class as an undergrad.

“I always thought having the chance to use my knowledge would be fun,” says Edwardson. “Being able to simulate what a pharmacist in the HEOR part of industry would do is invaluable.”

The HEOR portion of the process goes beyond the core parts of the drug approval process to focus on the long-term outlook of the drug.

“More and more payers are looking for real-world evidence that shows a drug is cost-effective and innovative enough to separate it from other drugs currently on the market,” explains Edwardson. “That was the unique angle Nick Friedlander and I took when drawing up our HEOR plan, to differentiate our group from the competition. I think the rest of our team made that easy for us to do.”

Already winners, learning valuable lessons

Regardless of how well the team places in the IPhO case competition, the experience of competing will prepare the students for successful careers in pharmacy. “Having a competitive perspective to be the best in what you do is important for success,” says Brooks. “We learned a lot throughout this competition that we can apply to our future careers.”

While the School of Pharmacy exposes its students to the pharmaceutical industry as a function of its curriculum, the subteam leaders say the VIP case competition has been an incredible learning experience that’s helping them to build important skills.

“Having a competitive perspective to be the best in what you do is important for success.” –Bernard Brooks

Norsten enjoyed the collaborative aspects of the project and learned valuable leadership skills as the medical affairs subteam leader. “This is probably the most group-based project I’ve been a part of during pharmacy school, which is important for any profession at the end of the day,” he says. “I learned to keep open communication with my group of qualified and passionate individuals. I gave them the resources to complete tasks and reminded them of deadlines.”

The team, mostly composed of first- and second-year PharmD students, plans to compete again next year. “We are trying to gain as much experience as possible so that we can be consistently successful in the coming years of IPhO competitions,” says Budde.

“I’m really proud of our team’s motivation and performance throughout this whole competition,” says Burghardt.

Learn more about what students learn in the PharmD program and the IPhO competition.