AACP-funded simulations train student pharmacists for the future of pharmacy practice

By Katie Ginder-Vogel

Photos by Todd Brown & Sally Griffith-Oh

A patient gets discharged from the hospital and goes to the pharmacy to fill a prescription. But there’s a mistake or redundancy with the prescription that doesn’t get caught until the patient’s first follow-up visit after discharge. By then, damage might already be done to the patient’s health.

This scenario, fueled by the disjointed communication between pharmacies and hospitals in different health systems, isn’t all that uncommon, but it can be detrimental to care.

“In practice, the members of the health care team aren’t always interacting with the patient or each other at the same time, in the same vicinity,” says Casey Gallimore (PharmD ’05, MS ’13), associate professor in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Pharmacy Practice Division.

So how can practitioners in different locations work together as a cohesive interprofessional health care team to prevent mistakes like these?

That’s the central question two School of Pharmacy simulations aim to train students to answer. Both projects are being funded by the American Academy of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) through Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SOTL) awards, which support faculty research that’s generating new knowledge to advance teaching and learning in pharmacy education.

One project, led by Gallimore, brings together pharmacy and nursing students to walk through identifying and preventing medication errors following hospital discharge. The second, led by Associate Professor Andrea Porter (PharmD ’06), who was selected for and is currently completing AACP’s year-long Academic Leadership Fellows Program, connects students from two pharmacy schools across the country to understand the challenges and advantages of telepharmacy.

“Patient education related to medication use is a fundamental skill for pharmacists, but is also a responsibility shared across health professions,” says Gallimore. “Using simulations like this to help students develop a shared understanding of and appreciation for the roles and responsibilities of care team members is important in today’s interprofessional practice landscape.”

Seamless transitions of care

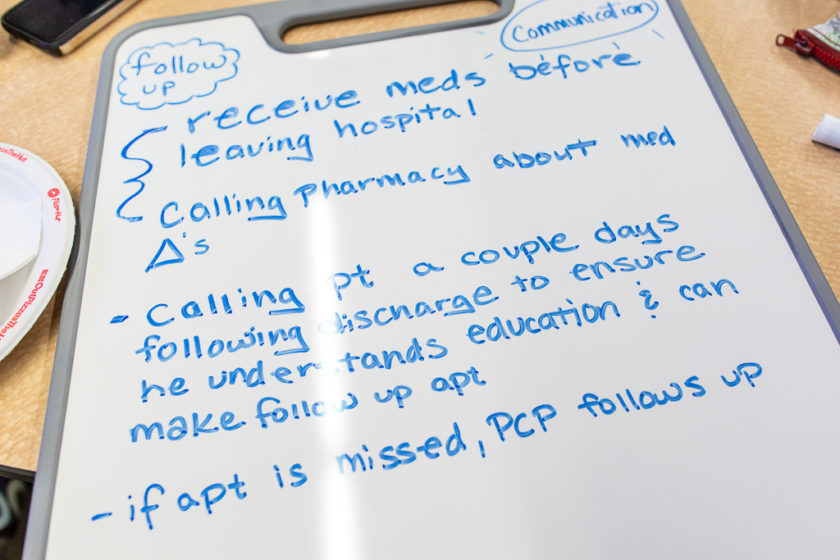

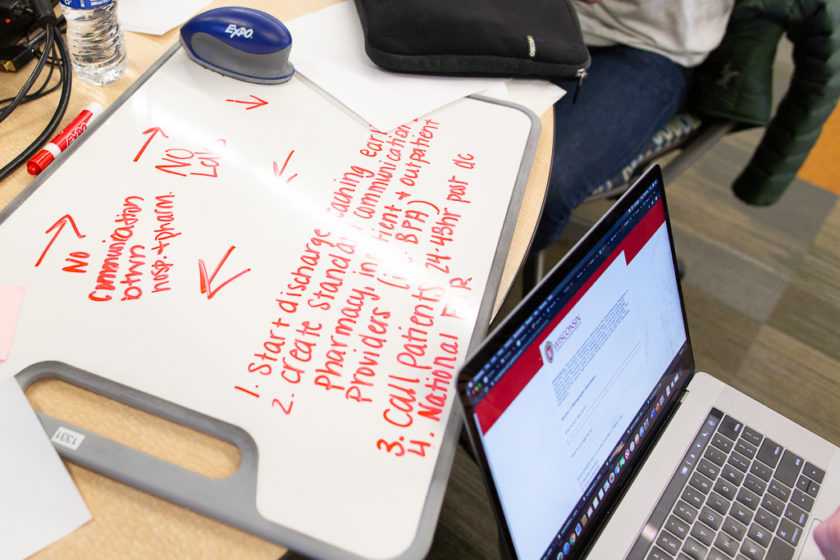

Much like in the above scenario, the simulation Gallimore is leading follows a patient’s health care journey after a hospital stay. The patient misunderstands their medication instructions at hospital discharge despite receiving appropriate education. When they go to a community pharmacy the misunderstanding persists because the pharmacist doesn’t have access to the necessary information that would alert them to the recent hospital admission and medication discharge instructions. This preventable error is therefore not caught until the patient follow-ups with their primary care provider at the point they are experiencing adverse effects.

“The scenario mimics real-life challenges, where patients transition across multiple settings with communication challenges between them,” says Gallimore. For example, pharmacies outside of a hospital’s health system often can’t see the patients’ electronic health record, which would contain information about recent hospital visits and prescription alterations.

“The intent is for students to participate in the care of an individual patient who experiences an adverse medication outcome and use this as a platform to facilitate interprofessional discussions around the bigger picture of transitions of care,” says Gallimore. “This is an opportunity for interprofessional student teams to understand and learn from errors.”

For a realistic interprofessional learning experience, Gallimore collaborated with Gina Bryan, a professor at the UW–Madison School of Nursing, School of Pharmacy Assistant Professor Ed Portillo (PharmD ’14), and the School of Nursing’s Center for Technology-Enhanced Nursing. In the first stage of the simulation, 18 PharmD students, 12 bachelor of science in nursing (BSN) students, and 18 Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) students first completed an online learning module and read an evidence-based article on transitions of care for interdisciplinary teams.

“In this pilot, students have an individual clinical experience as a registered nurse, pharmacist, or primary care provider,” says Bryan. “The care is given in three unique settings: an inpatient unit, the clinical pharmacy, and an outpatient clinic.”

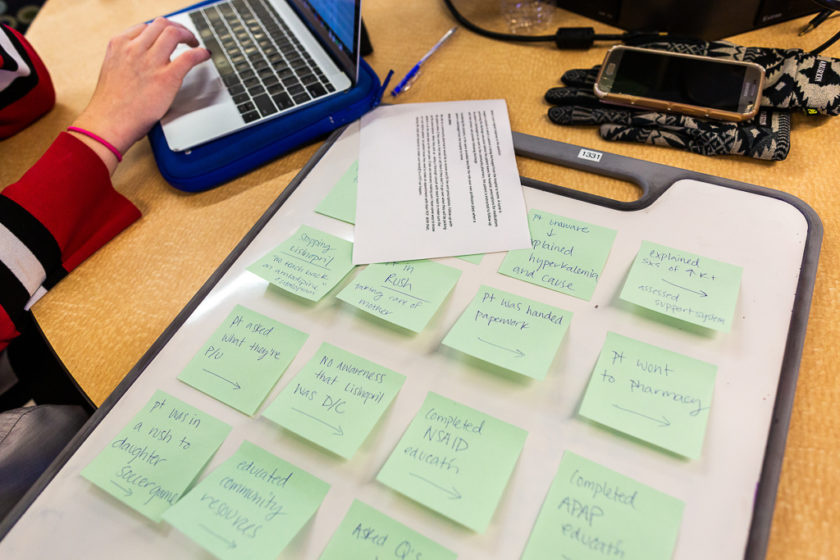

The pharmacy and nursing students each completed a separate simulation activity, in which they interacted with a standardized patient — a paid actor. First, the BSN students discharge the standardized patient from their hospital stay. Then, PharmD students consult with the patient during a community pharmacy visit. Then, the DNP students see the patient for their first follow-up visit following the hospital discharge, where they are supposed to discuss the side effects of discontinuing a medication.

“The link between the clinical and quality world is very important, and we tried to highlight how every clinician has a role in quality outcomes,” says Bryan.

“This activity is designed to empower students to collaborate as interprofessional colleagues, to improve the health care systems where we practice.”

—Ed Portillo

All the simulated visits are recorded, and the students and faculty later review each other’s interactions to provide feedback on patient communication and education.

In the final learning activity, students from all three disciplines come together to complete a root cause analysis of the transitions of care process to identify where the error occurred and how it could have been prevented.

“In this scenario, they are directly involved in the process of transitions of care for the same hypothetical patient, and they are able to see what happened at each state of that patient’s care. This allows students to reflect on the challenges they encountered, while also discussing the challenges their teammates faced in their interactions,” says Gallimore. “It’s a unique perspective.”

“This interprofessional simulation positions students to care for a patient during the transition from hospital to home and illustrates the importance of systems-level thinking,” says Portillo. “Students are really able to explore how vulnerabilities and breakdowns in our health care system can lead to patient harm.”

The first pilot took place in the Fall 2019 semester, and it will be repeated in Spring 2019.

“This activity is designed to empower students to collaborate as interprofessional colleagues, to improve the health care systems where we practice,” says Portillo.

Connecting with patients through telepharmacy

“Telehealth is a way to provide patients access to health care,” says Porter, who is also a pharmacist at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital. Through telepharmacy, a pharmacist utilizes technology, usually through computer access, videolink and audiolink, to oversee pharmacy operations and provide patient care services. The pharmacist and the patient or pharmacy technician are in different locations, which expands access for patients.

“In more urban areas, patients are in close proximity to and have access to health care. The Madison VA cares for patients who live in southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois. Not all of our patients live close to the Madison hospital or one of its community-based outpatient clinics. Because of that, the VA has implemented telehealth visits for patients. This can be very useful for patients who live in rural areas or who have difficulty getting to the clinic due to transportation and mobility difficulties,” she says. “This is one way that health care has become more accessible for patients.”

Considering the growth in telepharmacy and its ability to bring accessible care to rural populations, Porter is collaborating with Jeanne Frenzel, an associate professor of pharmacy at North Dakota State University (NDSU), to help student pharmacists feel confident providing support to a pharmacy technician and education to a patient at a remote pharmacy site.

Eleven third-year PharmD students enrolled in Integrated Pharmacotherapy Skills III at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy and the Pharmacy Practice Laboratory IV at NDSU participated in the two-part study.

In the first activity held in November 2019, students practiced verifying a prescription for oral and IV medications remotely and had the opportunity to play the role of both the pharmacist and pharmacy technician. Errors were built into each scenario for students to try to identify and address.

The second activity, which will be held in spring 2020, simulates a remote patient consultation utilizing videoconferencing software. During this activity, students will have the opportunity to play both the pharmacist and patient roles.

Both activities are being recorded for faculty to assess, and students also complete surveys and reflections before and after each activity to share their perspectives and feedback.

“Learning and interacting with a new telehealth simulation software, in affiliation with pharmacy students from NDSU, was a rewarding and beneficial experience,” says Anna Lattos, a third-year PharmD student at the School of Pharmacy.

“We got the rural pharmacy experience of telepharmacy and how it may feel, as a pharmacist, to check and verify prescriptions from a different location than the technician and learned the importance of a trusting partnership between the pharmacist and technicians within these sites.”

“Having experienced first-hand the learning curve associated with telepharmacy services, I am excited to provide students the opportunity to practice these skills in a safe environment.”

—Magdalena Siodlak

Magdalena Siodlak (PharmD ’17), a second-year ambulatory care pharmacy resident at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, is assisting Porter with the simulation.

“During my clerkships as a student and as a resident, I’ve used telepharmacy to verify sterile products and to lead patient clinic visits,” Siodlak says. “Having experienced first-hand the learning curve associated with telepharmacy services, I am excited to provide students the opportunity to practice these skills in a safe environment.”

A team-based future

Gallimore, Portillo, and Bryan are developing a scalable plan for other schools to implement this type of simulation — even pharmacy schools without a nursing or medical school nearby.

“Most schools of pharmacy and health professional schools struggle to develop quality interprofessional education, due to logistical barriers, such as not having on-campus collaborators,” says Gallimore. But these simulations could be done remotely, and the briefing takes place online.

The group also plans to present the pilots’ results at the 2020 AACP annual meeting and disseminate the results to a broader audience, by presenting or publishing them in an interprofessional education-focused journal or conference.

Porter hopes that this simulation will not only contribute to pharmacy student development at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy and NDSU, but also to plans to publish the results to share how pharmacy schools can collaborate on student skills-based research projects, which promotes the standardization of assessment rubrics and supports a culture of professional development.

“Individual faculty members and instructors within one institution often collaborate on projects, but this project is unique in that it involves students from two different schools of pharmacy interacting in real time, which is less common,” says Porter.

Long-term, Porter envisions expanding the activities to all third-year pharmacy students at both institutions, or even including additional institutions or telemedicine activities, such as a medication therapy management session.

“It is incredibly important to provide students opportunities to practice pharmacy skills and provide feedback on their performance in the classroom to prepare them for pharmacy practice after graduation,” says Porter. “This project provides students exposure to telepharmacy, an area in which our students may be practicing in the future.”