School of Pharmacy faculty partner with Michigan State to influence OTC label regulations

By Katie Gerhards

Think of an older adult in your life, who is still living independently and keeping up with a complicated regimen of a dozen medications, including a recent prescription for warfarin, a blood thinner. Picture them walking through the aisles of their local pharmacy, looking for something to curb aches and pains.

The familiar brand names make it easy for them to pick one from the shelf and toss it into the cart without too much worry or research—they’ve been taking over-the-counter (OTC) medications for decades and have never had a problem. But what they don’t know is that taking the aspirin sitting in their cart in combination with warfarin could increase their risk of major bleeding—even something as simple as Alka-Seltzer, ibuprofen, or vitamin K could have problematic effects.

Pharmacists already know that common OTC medications can have threatening interactions with prescription medications, or even certain health conditions. But the average person might have no idea, and the more numerous the medications, the more difficult it becomes to decide if medication is safe.

“Older adults are at a higher risk for adverse drug reactions because of their typically complex medication regimens and health conditions,” says Professor Beth Martin (BS ’90, MS ’03, PhD ’06) in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Pharmacy Practice Division.

By partnering with the Michigan State University School of Packaging, Martin and Associate Professor Bob Breslow (BS ’75), also in the School’s Pharmacy Practice Division, want to ultimately influence national regulations around OTC labeling to promote the safety of older adults.

“Although packaging might not be the most obvious response to wicked problems related to health, it has the potential to favorably impact them,” says with Laura Bix, a professor in the MSU School of Packaging who leads a group called the Packaging HUB (Healthcare, Universal Design and Biomechanics).

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) recently awarded this collaborative project, “Optimizing OTC Labels for Older Adults,” a five-year, $1.6 million grant to leverage eye-tracking technology to determine what information older adults are reviewing on OTC labels, what they should be looking at, and how the positioning of that key information can help patients make safer medication decisions.

Understanding the problem

The funding for this project officially started in July 2018, but the groundwork goes back several years, with Martin going shopping at Walgreens with Bix.

The two had met months earlier on an advisory panel for the Gerontological Society of America, during which time they discussed the inappropriate use of OTC medications among older adults, and decided to team up.

“I think that the real strength of this collaboration is that, as a research team, we are quite unique and well-qualified for this project,” says Bix. “Our breadth of backgrounds and expertise (gerontology, pharmacy, cognitive psychology, and packaging) allow us to translate concepts from fundamental into practical approaches that can be applied to the creation of regulations with the goal of enhancing public health.”

A few months after the panel meeting, Bix visited Madison and went to Walgreens with Martin to assemble groups of products to ask older adults which is the most appropriate and safe for them to use.

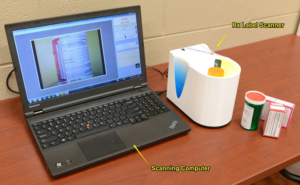

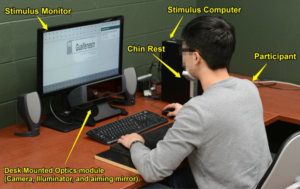

MSU took those groups, scanned in the medications’ labels, changed some of the names, and then recruited older adults and asked them to determine whether or not the product was appropriate for them to take while wearing a device that tracked their eye movements.

“Using the pupil and corneal reflection, the device can determine what people are looking at, how long they spend, what portion of the box panels they’re flipping to, and how much information they were actually viewing,” says Martin.

Not surprisingly, they found people were more likely to look at the package front, and spend most of their time there as well. Rarely did they read through the safety precautions on the back panel. One possible explanation for this behavior is offered by focus groups the team ran this summer. When asked about their decision-making process with OTC drugs and the information older adults use for the same, participants consistently tended to perceive OTCs as innately safe, particularly for those drugs that were already familiar.

As part of the eye-tracking study, Bix and her team gathered medication and health histories (based on a protocol validated during Martin’s earlier research projects) to assess participants’ answers to the question, “Is this appropriate for you to take?”

Afterward, Martin and Breslow—brought into the project because of his expertise in gerontology—reviewed the appropriateness or inappropriateness of the patients’ choices in a group of OTCs, based on the patients’ provided health information.

When participants were only given the name of the active ingredient in a medication, they incorrectly deemed the medication to be safe for them 37 percent of the time, according to Martin and Breslow’s review of their health history. When the same active ingredients appeared on mock drug packages, participants erred 63 percent of the time, which suggests that packaging is a strong factor in older adults’ health care decisions.

This early research formed the basis of the grant application to AHRQ, and set the team up for the first step in the funded study: a survey.

Embarking on a quest for change

An initial survey of roughly 4,700 pharmacists, from the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy and American Society of Consultant Pharmacists, will help focus upcoming trials. In the survey, which Breslow and Martin hope to release this fall of 2018, pharmacists will rank the importance of various types of information in reducing the likelihood of adverse drug reactions, which will then inform MSU’s next moves.

With the survey data, the MSU team will conduct a series of studies testing new OTC labeling designs, moving different types of information—such as active ingredients, drug interactions, and the key points pharmacists chose as most important—to the front panel of OTC labels. They’ll also highlight different pieces of information to monitor the impact of the design strategy on patients’ eye movements and medication decisions.

“We have a great opportunity to make older adults safer.” –Beth Martin

The study will also incorporate a variety of OTC medication types, from pain and allergy relievers, to sleep and stomach aids.

After those trials are complete, and after Martin and Breslow review the appropriateness of participants’ decisions, the researchers will pore over the data and see whether the proposed strategy for design results in better attention to important information, and, ultimately, better assessment of appropriateness by patients.

“The final step in the project is influencing policy, disseminating results and getting them to key decision-makers about packaging regulations,” says Martin. “We have a great opportunity to make older adults safer.”

Learn more about Dr. Martin’s research career.

Read about other initiatives at the School of Pharmacy to improve medication safety, such as Associate Professor Michelle Chui’s research into CancelRx and Assistant Professor Olufunmilola Abraham’s opioid safety video game.