Postdoctoral Research Associate Sarah Neuman discovers, names ‘hobbit’ genetic mutation in quest for diabetes treatments

By Katie Gerhards

In a fly in a lab there lived a hobbit. Not a fat, large-footed hobbit eagerly awaiting second breakfast, nor yet a hobbit with curling warm brown hair on the brink of adventure.

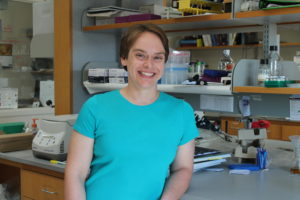

This hobbit, rather, is a genetic mutation recently characterized and named for the first time, by Sarah Neuman in the lab of University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy Associate Professor Arash Bashirullah. In 2017, Neuman completed her PhD in the Bashirullah Lab in the School’s Pharmaceutical Sciences Division and is now continuing her research there as a postdoctoral scholar.

“Mutants of this gene had a really interesting phenotype—the animals were really small,” says Neuman. “I got to name it, and I’m a bit of a Tolkien nerd, so I decided to name it ‘hobbit’ because of the really dramatic, small phenotype.”

“There was no guarantee that this characterization would be impactful or important, and that was the risk. But she pursued it anyway.”

–Arash Bashirullah

But, without yet knowing why the affected fruit flies were so small, her hobbit journey didn’t stop there. After mapping and naming the gene, Neuman embarked on a research journey that would last years. The destination: a new insight into diabetes treatments.

An unexpected career

Despite her notable accomplishments and awards in bioscience, Neuman, also a longtime flutist, originally had a very different path in mind.

“When I started college, I was absolutely sure I wanted to be a high school band director,” she says. So she started her undergraduate studies with a double major in music education and biology at Lakeland University in Sheboygan, Wis. “Honestly, biology was the backup.”

But her plans changed as she started conducting research for her biology degree. “I caught the bug,” she says. After graduation—with degrees in music performance and biology—she enrolled in the Cellular and Molecular Biology (CMB) graduate program at UW–Madison, which is a cross-campus biomedical sciences PhD program that includes nearly 200 faculty member research mentors, including the School of Pharmacy’s Bashirullah.

“When I interviewed with the CMB program at UW, it just felt right,” says Neuman. “I met with faculty who were doing some really amazing and exciting science. Plus, it’s hard to beat the ‘vibe’ that is uniquely Madison.”

The research journey

Neuman started her hobbit gene research six years ago, as a new CMB graduate student in Bashirullah’s lab. As it turned out, the decision to trade in her flute for fruit flies in his lab resulted in a discovery that could impact the future of diabetes treatment.

“In my first week as a grad student, faculty members introduced their areas of study. Dr. Bashirullah presented on how animals can avoid apoptosis, or cell death, and how at some stages of development animals are immune to apoptotic triggers, while in other stages they are sensitive,” she says. “I was interested in how that switch is regulated, and how that’s related to cancer, which also evades cell death.”

But when she started in the Bashirullah Lab, which focuses on the genetic study of metamorphosis-specific mutations, there was another project in the lab that was at a good spot for her to pick up. Bashirullah had previously conducted a mutagenesis screen for mutations that are lethal during metamorphosis and identified a several mutant strains with a small body size phenotype. But he hadn’t studied them any further.

When Neuman started in his lab, she mapped one of these small body size mutations to a gene that was completely uncharacterized. About two-thirds of our more than 20,000 genes are unstudied, according to Bashirullah. “It’s like reading a text where you don’t know the verbs,” he says.

But, because hobbit is present in yeast, one of the simplest eukaryotic organisms, as well as in more complex organisms like fruit flies and humans, they knew it likely plays an important role in the basic biology of the cell.

“There was no guarantee that this characterization would be impactful or important,” says Bashirullah. “And that was the risk. But she pursued it anyway.”

Flies and science

In uncharted territory, Neuman, with Bashirullah’s guidance, conducted unrelenting experiments for three years, while also pursuing a handful of other research projects. After years of work, in April 2015 she, with relief and excitement, at last uncovered why hobbit mutant animals were so small.

“I think it did take a lot of bravery and fearlessness to keep fighting through and keep testing new ideas to get to the end result.”

–Sarah Neuman

“I still remember exactly how I felt looking at the samples under the microscope,” she recalls. “I was actually quite nervous to look at the samples, because I had really high hopes for the experiment, and I was really hoping that my hypothesis was right.

When I saw that there was an insulin secretion defect, it was one of the most amazing moments I’ve experienced as a scientist so far. I knew that I had found something really cool and very important, and it was just an incredibly exciting moment.”

The reason that the hobbit mutant animals are small is because they fail to secrete insulin. Fruit flies have insulin and the same basic secretory mechanisms as humans, Neuman explains. The only difference is that in people, insulin only regulates metabolism and an insulin-related growth factor regulates growth, whereas in the flies, those two functions are combined, which is why the fruit flies that don’t secrete insulin, in addition to having metabolic defects, are smaller.

“This finding wouldn’t have been possible without her drive for excellence and discovery that continuously pushes her to improve,” says Bashirullah. But he says the development also hinged on the freedom and support of the School of Pharmacy. “We have an intellectual environment that is extremely supportive of pursuing our interests, our curiosity,” he says. “We couldn’t have predicted this, but we had the freedom to study it anyway.”

Neuman’s exploration of hobbit was a central piece of her award-winning PhD thesis, “Characterization of Hobbit, a Novel and Conserved Regulator of Intracellular Trafficking During Regulated Exocytosis.” For her “exceptional scientific perspective” and “intellectual fearlessness” she proved through her thesis, the CMB awards committee honored Neuman with the 2017 Exceptional Thesis Award. The same research also earned her a Discovery Challenge Award from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.

“Taking on a project like hobbit, where you have this thing that’s brand new and it doesn’t look like anything else that’s been characterized, with no known function—and then trying to figure out what that does is a very big task. I’m not sure that as a first-year grad student I fully comprehended what I was taking on. But I’m very glad that it worked out,” she says of the Exceptional Thesis Award. “I think it did take a lot of bravery and fearlessness to keep fighting through and keep testing new ideas to get to the end result.”

The next stage

As part of the School’s Pharmaceutical Sciences Drug Action Core, this research is taking a genetic approach to understanding the “downstream” effects of medication and what it’s targeting. “There aren’t very many effective drugs to treat Type 2 diabetes, and part of the reason that we don’t have more treatments is because we don’t have good drug targets,” Neuman says.

Given the hobbit mutation’s connection to insulin, Neuman hopes that hobbit could be a new drug target for future treatments for diabetes. She will test this by giving the “hobbit” mutant fruit flies different drugs and testing if any of them rescue the small body size and insulin secretion defect. Since the human protein and fruit fly protein can substitute for each other functionally, this testing might be a new way to find novel human diabetes treatments.

“When I saw that there was an insulin secretion defect, it was one of the most amazing moments I’ve experienced as a scientist so far.”

–Sarah Neuman

“A lot of people don’t appreciate the power of the fruit fly to test these types of things,” says Neuman. “About 75 percent of human disease genes are also present in the fly, so we can learn a lot about human diseases and how the human body works in general by studying the fruit fly.”

Now that hobbit has been characterized, Neuman and her undergraduate research assistants—who include PharmD, Pharm-Tox, pre-pharmacy, and biology students—are continuing to explore the more detailed molecular mechanisms at play, such as which proteins it’s binding to and how it’s regulating insulin secretion.

Although, according to Bashirullah, Neuman could easily pursue her postdoctoral studies in anyone’s lab in the world, she wants to stay at UW–Madison. Following her postdoc work, she hopes to become a staff scientist in the Bashirullah Lab.

“I’ve come to genuinely love this university and this city,” says Neuman. “Plus, here at the School of Pharmacy, I have the opportunity to keep working on hobbit, a project where I can really carve out a niche and keep exploring—I’m really an explorer at heart.”

Learn more about the School of Pharmacy’s PhD in Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Read about the research in the Bashirullah Lab.