Our project, informed by resilience engineering, will address the challenges common in community pharmacies to achieve safe medication use in community-dwelling complex patients with multiple chronic conditions. The resulting outcome, the Engineering Resilient Community Pharmacies (ENRICH) Patient Safety Learning Lab, is expected to gain knowledge of strategies for building resilience capacity in community pharmacy work systems in conducting CCM.

Over 100 million Americans, who have multiple chronic conditions, experience greater than one million adverse drug events (ADEs) annually, costing the U.S. healthcare system over $8 billion per year. Harm associated with unsafe medication management is significant and represents a major threat to the health of all Americans. Community retail pharmacists are ultimately responsible for ensuring patients’ safe medication use and fill a substantial primary care gap in medically underserved communities. Their efforts are continually challenged, however, by volatile work demands, inconsistent patient or caregiver expectations and engagement, and lack of employer recognition that pharmacists work at the boundary conditions of the system.

Pharmacists have expanded patient care services to include chronic care management (CCM), facilitating a holistic review of a patient’s history to address complex and interacting medication use problems. However, these services have not been reimbursable, making them unsustainable in a chaotic work system. Medication safety in community pharmacies is a complex, nonlinear, and multi-dimensional issue shaped by system forces and interactions among pharmacists, primary care providers, patients and families.

Our Systems Approach to Medication Safety (SAMS) Lab has conducted studies to develop and evaluate targeted interventions to address hazards in the community pharmacy work system (AHRQ R18HS024490, R18HS027737, R21 HS025793). While these interventions demonstrated effectiveness at reducing harm, they emphasized “what went wrong” and shifted the focus away from the vast majority of times that care is delivered properly, sometimes referred to the Safety-I approach. Further, stacking isolated interventions will not result in fundamental changes in medication safety in ambulatory and community settings.

Our long-term goal is to transform community pharmacies to apply equal emphasis on “what goes right,” or a Safety-II perspective, by (1) innovating and developing sustainable solutions that optimize interactions among pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, patients, and caregivers and (2) building capacity and infrastructure to expand research in this critically needed area. Safety-II leverages the ability of pharmacists and technicians to adapt to unpredictable situations and identify work system components that improve such resilience.

In 2023, Wisconsin pharmacists will gain “provider status” pursuant to legislation passed in 2021, facilitating the integration of pharmacists in patient-centered team-based care and increasing sustainable and reimbursable CCM to Wisconsin patients, two-thirds of which live in counties that are considered medically underserved. This legislation is a fundamental change that will reduce system factors such as misalignment of incentives, imperfect care coordination, and information gaps. This new law presents a timely opportunity to address an unmet critical need, identified by AHRQ PA-21-266 to “stretch professional boundaries, envision innovative designs, and take advantage of rapid prototyping techniques” to improve medication safety for medically underserved, complex patients, an AHRQ targeted population at high risk for adverse drug events.

Accordingly, our hypothesis is that medication safety relies on the capacity of pharmacists and technicians to work together, under complex, unexpected, and ever-changing circumstances, and their ability to adapt to become more resilient. Our transdisciplinary team will collaborate with 3 pharmacy organizations to create and evaluate a system of CCM that supports safe medication use. The CCM system design will focus on creating and evaluating the “Medication Safety Map” (MedSafeMap) for community-dwelling complex patients, which could include information artifacts and task redesign. We will leverage participatory design, and human factors and systems engineering tools and methods to develop solutions.

Aim 1. Identify and define community pharmacy work system design requirements for safe medication practices to enable resilient performance.

Aim 2. Design and develop MedSafeMap, a feasible and sustainable solution that facilitate safe medication practices through resilient performance.

Aim 3. Implement MedSafeMap in community pharmacies and pilot test its impact on pharmacy staff attitudes, behaviors, and performance.

To ensure as complete an understanding of the problems and implementation strategies of varied community pharmacy work systems, we will partner with 3 pharmacy organizations to conduct the problem analysis (Aim 1) and implement and evaluate prototypes (Aim 3). Two pharmacy locations from each of the 3 organizations will participate. Locations were selected based on their diverse patient population.

We will also partner with Fitchburg Family Pharmacy to conduct in-situ simulations, in which we will use simulated complex patient scenarios in a pharmacy itself rather than in training facilities, for the design and development phases (Aim 2) of the project. Fitchburg Family Pharmacy is a medium-sized urban independent pharmacy that provides CCM to a diverse patient population. We will conduct the simulations on a Sunday when the pharmacy is closed for business.

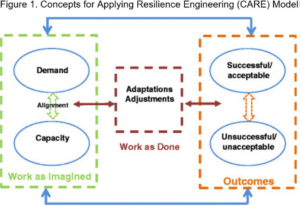

The Concepts for Applying Resilience Engineering (CARE) model guides our data collection, analysis, and interpretation (see Figure 1). Resilience is the ability for the community pharmacy work system to adjust its functioning prior to, during, and following sentinel or unexpected events, and thereby sustain operations under both expected and unexpected conditions. It assumes that variability in the environment creates the need for adjustment. Work as Imagined (WAI) is conceptualized as the intended, or imagined, alignment between demands of the system (prescription volume, patient acuity) and the capacity to meet those demands. Demand and capacity can never completely align because of the complex nature of the system – there will always be unforeseen demands that require workers to adjust in situ. In addition, workers do not simply comply with protocol but naturally adapt and innovate as part of taking control over their environment. In the CARE model, Work as Done (WAD) refers to the adjustments and the natural variability in how tasks are carried out. Predicting acceptable (what goes right) and unacceptable (what goes wrong) outcomes depends on an understanding of WAD in different demand and capacity circumstances.

The Concepts for Applying Resilience Engineering (CARE) model guides our data collection, analysis, and interpretation (see Figure 1). Resilience is the ability for the community pharmacy work system to adjust its functioning prior to, during, and following sentinel or unexpected events, and thereby sustain operations under both expected and unexpected conditions. It assumes that variability in the environment creates the need for adjustment. Work as Imagined (WAI) is conceptualized as the intended, or imagined, alignment between demands of the system (prescription volume, patient acuity) and the capacity to meet those demands. Demand and capacity can never completely align because of the complex nature of the system – there will always be unforeseen demands that require workers to adjust in situ. In addition, workers do not simply comply with protocol but naturally adapt and innovate as part of taking control over their environment. In the CARE model, Work as Done (WAD) refers to the adjustments and the natural variability in how tasks are carried out. Predicting acceptable (what goes right) and unacceptable (what goes wrong) outcomes depends on an understanding of WAD in different demand and capacity circumstances.

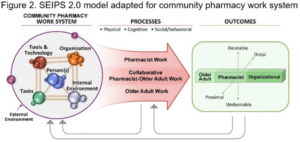

Since resilience also applies to the organizational level, and to adaptations in complex systems, it is essential to ensure that characteristics and adaptations of the entire work system are captured. To operationalize the discrete facets of the work system, we will use Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) 2.0, a human factors engineering model to improve patient outcomes (see Figure 2). The SEIPS model has framed the design and analysis of many safety studies, including research we conducted in community pharmacies (see C.2).

The CARE and SEIPS models work well in tandem because both models contain feedback loops and account for the interconnectedness of work system components.

Aim 1 will focus on problem analysis of the work system through observations and interviews of stakeholders, and analyses of pharmacy work system information flow and artifacts. These activities will lead to the development of resilience narratives and FRAM models that will illustrate relationships among work system features that will be addressed in subsequent aims.

Aim 2 will employ participatory design and pharmacy-based (in situ) simulations to create a MedSafeMap, a package of components to optimize pharmacy staff interactions within their work system and with patients and detailed pharmacy design recommendations.

For Aim 3, a mixed-methods evaluation will be used to pilot-test the impact of MedSafeMap to improve pharmacy staff work system resilience and medication management around CCM, while also resulting in a Toolkit and Implementation Guide.

Principal Investigators

Co-Investigators and Collaborators

Research Staff

Advisory Board