This toolkit outlines our approach to engage patients as partners in developing a community pharmacy system level intervention to improve OTC safety for older adults.

This study examines effectiveness of an innovative pharmacy design change on over-the-counter (OTC) medication misuse in adults older than 65. A structural pharmacy redesign (the Senior Section™) was conceptualized to increase awareness of higher-risk OTC medications. The Senior Section contains a curated selection of OTC medications and is close to the prescription department to facilitate pharmacy staff/patient engagement to reduce misuse.

Adverse drug events (ADEs) associated with over-the-counter (OTC) medications cause 178,000 hospitalizations each year, representing a major patient safety concern. Older adults aged 65+, one of AHRQ’s priority populations, are particularly vulnerable to ADEs. Of the 2.2 million older adults who are at risk for a major ADE, more than 50% of older adults are because of concurrent use of an OTC and prescription medication.

Community retail pharmacies, where most older adults purchase OTC medications, are unique health care settings characterized by extended hours and access to a pharmacist who can provide free medication guidance. Unfortunately, the design of most community pharmacies is poor and contributes to misuse of high-risk OTCs.

Aim 1. To refine the system redesign intervention and implementation strategy through diagnostic and formative evaluation.

Aim 2. To evaluate the effectiveness of a refined system redesign intervention on preventing misuse of high-risk OTC medications by older adults.

Aim 3. To evaluate the implementation of a refined system redesign intervention in community pharmacies.

This study took place in four Shopko Stores in Wisconsin. Shopko Stores was a chain of mass merchandise stores with multi-department operations. The company operated over 300 stores located in 20 states, typically in small to mid-sized communities. Most Shopko Stores had a pharmacist available the majority of time that the store was open, and stocked several large aisles of OTC products. Unfortunately, during post-intervention data collection, Shopko stores filed for bankruptcy and closed all sites.

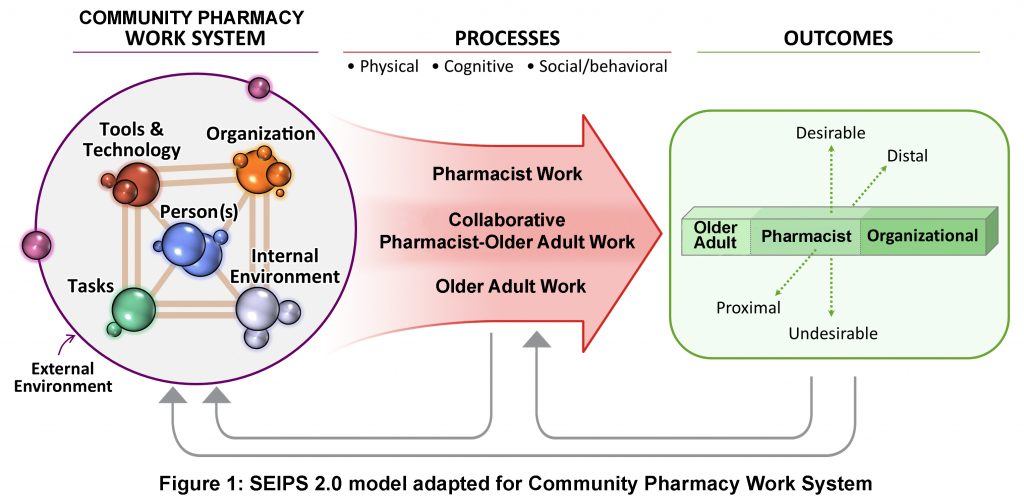

The conceptual framework for this intervention is adapted from the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) 2.0 work system model to improve patient outcomes, a human factors engineering model developed by Holden et al. The SEIPS Model has been applied to frame the design and analysis of many patient safety studies, including research conducted in community pharmacies. The SEIPS 2.0 model is appropriate for this study because it emphasizes how work system barriers can impact the “work” conducted by pharmacists and older adults. Work is defined as goal-oriented, effortful activities. For pharmacists, work would include clarifying an older adult’s medication list or determining if the older adult should self-treat their stated problem. Older adult work would include determining how often to take an OTC medication or if an OTC medication interacted with prescription medication. This model is also appropriate because it highlights the importance of collaborative work, in which pharmacists and older adults are actively engaged agents, working together to achieve their goals. These work processes in turn affect older adult, pharmacist, and organizational outcomes.

To develop the Senior Section, 5 pharmacy staff and 5 older adults were recruited into two separate stakeholder groups. The stakeholder groups met for 6 iterative participatory design sessions to clarify the problems from their own perspectives, to brainstorm strategies, and to prototype the intervention, which became the Senior Section. Each session was developed to include a variety of active participation activities, targeted for the perspectives of each stakeholder group. Utilizing participatory design provided a framework for incorporating feedback from each session in the preparation of the subsequent session. Participatory design was an effective and necessary approach to understand the needs of end-users so that the final intervention fit with the existing work system.

Following the participatory design, the Senior Section was beta-tested in one pharmacy. Using Proctor’s implementation outcomes as the guiding framework, we sought formative evaluation from stakeholders. To ensure compatibility and practicability, stakeholders stressed the importance of the intervention having limited impact on routine processes and close proximity to the prescription department. The intervention was perceived as feasible – it minimally affected both workflow and overall OTC consult time. Prioritizing specific implementation outcomes during the design process allowed us to address these barriers early on and foster buy-in. This formative data collection allowed for rapid cycle improvement of the Senior Section.

Five Senior Section features facilitate older adults’ safe OTC medication selection:

Our project required 72 older adult participants pre- and post-implementation in order to be powered for a 45% reduction in OTC medication misuse. The pharmacy organization partner filed for bankruptcy during our post-implementation data collection period. As a result, we were only able to recruit 15 older adult participants in the post-implementation period.

Patient characteristics (age, gender, race, education, number of prescribers, pharmacies, and medications, health status, and total health) revealed few notable differences in patient samples between pre- and post-implementation.

At pre-implementation, no patient had an educational level below high school, but one patient reported education up to eighth grade at post-implementation. The number of medications that patients reported taking also was narrower at post-implementation (pre-implementation min/max: 1-33 vs. post-implementation min/max: 6-18), but this did not translate into any distinction between means. In addition, over 60% of patients had a total health rating of very good/excellent prior to Senior Section implementation, while only a third of patients had the same rating at post-implementation. Despite these slight differences, no patient characteristic varied significantly between pre-/post-implementation and were considered homogeneous. Given these descriptive results, it is not surprising that the effect of patient characteristics (when added to the regression models as propensity scores had little if any adjusting effect on most misuse outcomes.

Even given the limited sample size, there were significant reductions in OTC medication misuse. Drug/Disease Misuse significantly lessened over time (z=-2.09, p=0.037). Drug/Label Misuse varied according to the sub-type, with reduced Daily-Dosage (z=-2.42, p=0.016) and Single-Dosage misuse (z=-5.82, p=0.001).

Importantly, the intervention fit with pharmacists’ workflow, did not add to pharmacist workload, and facilitated pharmacist-patient communication. The Senior Section improved the quality of pharmacist-older adult encounters. After Senior Section implementation, pharmacy staff were more likely to initiate (and be involved in) patient encounters, address more topics or problems/symptoms, provide details about OTC products, discuss appropriateness of OTC use, and discuss medication classes highlighted in the Senior Section. Because of the proximity to the prescription department, pharmacy staff were less likely to need to leave the prescription department for extended periods and had fewer prolonged encounters. Pharmacy staff noted no barriers that would reduce Senior Section utilization.

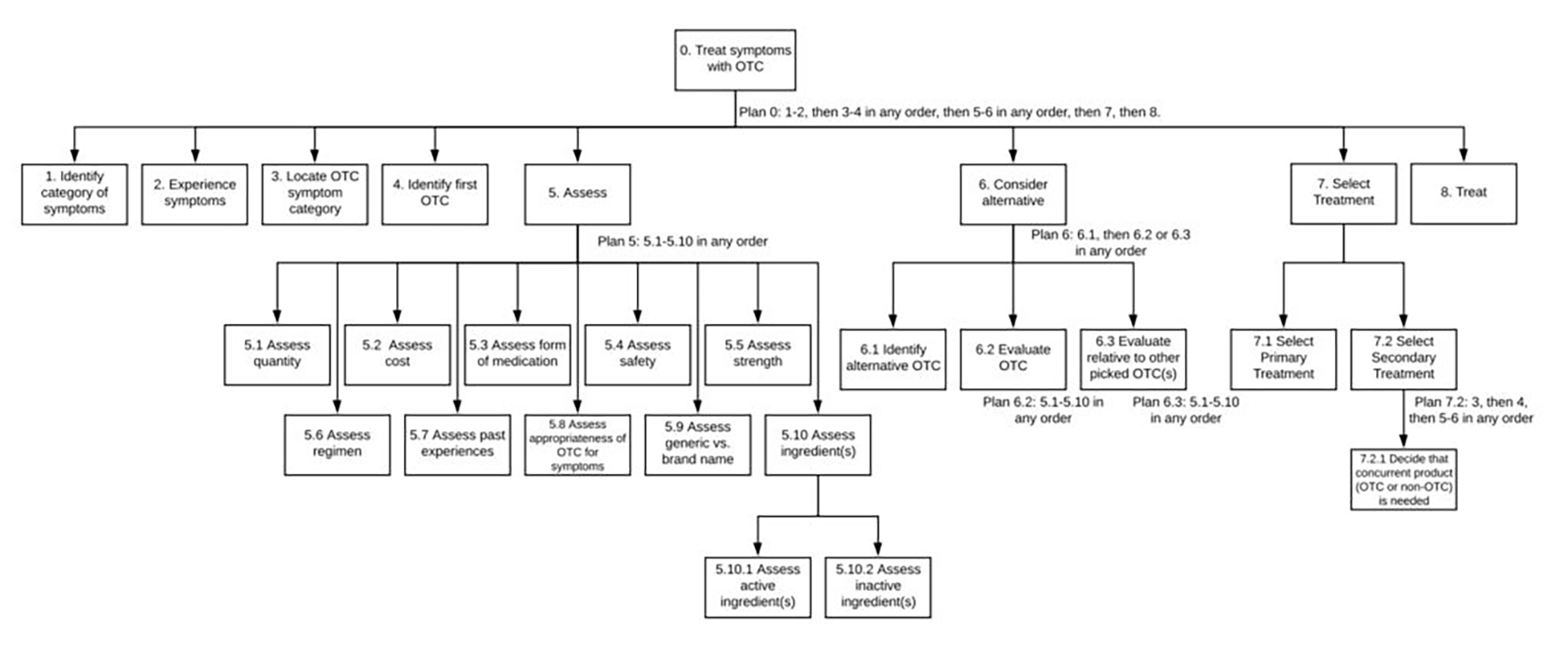

Using data from a sample of older adult interviews (9 pre- and 3 post-implementation), we conducted a cognitive task analysis to compare the effect of Senior Section implementation on shoppers’ decision-making processes. Cognitive task analysis (specifically hierarchal task analysis, because it provides significant insight into a task being analyzed by describing the specific goals, subgoals, operations, and plans of that task) allows determination of whether the intervention improves decision-making (e.g. reduces the number of choices) and where it does not (e.g. information is still hard to process). Our hypothesis was that the intervention would influence older adult decisions and would predict medication choice appropriateness.

Analysis showed that decision-making did not differ between shoppers who use the Senior Section and those who use the normal OTC aisles to select a product. However, a closer examination of the way these two groups assess a product and consider alternatives provides unique insight into the Senior Section’s impact. As expected, decisions involved a multitude of factors, all of which are indicated in steps 5.1 to 5.10 above – some factors related to product safety (steps 5.4, 5.5, 5.7, 5.8, and 5.10), while others indicated shopper preferences (steps 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.6 and 5.9).

| Assess Step | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 5.10 | 5.10.1 | 5.10.2 | Average number of factors considered in decision process |

| PRE | 78% | 78% | 56% | 44% | 44% | 67% | 67% | 56% | 67% | 56% | 22% | 0% | 6.3 |

| POST | 33% | 33% | 0% | 33% | 33% | 67% | 33% | 67% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 33% | 3.3 |

After Senior Section implementation, the average number of factors that older adults used to make a decision reduced from 6.3 to 3.3, while two-thirds of shoppers considered the appropriateness of the OTC for their symptoms (step 5.8) (compared to 56% pre-implementation). When shopping from the Senior Section, older adults no longer considered the form of the medication (step 5.3), generic vs name brand (step 5.9), and ingredients (step 5.10), and were less likely to consider steps 5.1, 5.2, 5.4, 5.4, 5.5, and 5.7.

Back row: Corey Lester, Richard Holden, Steven Albert, Cindy Phelan.

Front row: Nora Jacobson, Michelle Chui, Jamie Stone, Apoorva Reddy

Principal Investigator

Co-Investigators and Collaborators

Research Staff

Development of Senior Section through Participatory Design

PD actively involves stakeholders in designing effective, sustainable interventions. In contrast to traditional design approaches rooted in designers’ assumptions of users’ needs, we engaged our end-users in designing a multi-dimensional, community pharmacy-based solution aimed at reducing OTC misuse. Our PD process was a series of six adaptive sessions eliciting creation and reflection:

Older adults and pharmacy staff were engaged in four separate but concurrent PD sessions. The final two sessions united both stakeholder groups. PD sessions involved interactive group exercises that prompted reactions to multimedia and challenged participants to build and discuss physical representations of even their most outlandish ideas. Each session served to bridge experience with learning and inspire innovative, problem-solving frames of mind. In accordance with PD guidelines, the plan for each session was developed from analysis of the preceding session’s feedback.

View Participatory Design (PD) Session Scripts

See “Applying Participatory Design to a Pharmacy System Intervention” for more information.

Following the participatory design phase, the Senior Section was implemented in one beta store. The purpose of the beta phase was to both refine the Senior Section as well as the data collection tools.

Tools to Evaluate the Senior Section

Older Adult Interviews

Each consented older adult participated in a face to face interview. Participants were met by the interviewer near the store entrance. After collecting study materials and answering any participant questions, the participant was asked to choose one of the following symptom scenarios that applied to them:

The trained researcher asked the older adult to articulate the medication they are searching for and the decisions involved in making the selection. The researcher elicited this information by asking the participant to “think aloud” and use such probes as “what are you thinking now?” and “are you considering any other options here?” These probes helped us understand the older adult’s so-called “work,” (goal-oriented effortful activities) as they selected an OTC medication. We also asked specific questions about the information that they used to make their OTC medication decision, such as cost, previous experience with a particular medication, and label warnings.

Following the walking interview, a short semi-structured interview was conducted to gather information on how the older adult intended to use the medication (e.g. dosing and duration). The entire interview took 30–45 minutes. Additionally, for those older adults participating in the study post-intervention, we asked questions specifically related to the feasibility, usefulness, and acceptance of the intervention. Interviews were recorded using a GoPro video and audio. Following transcription of the interviews, observations that were recorded in the video (e.g. pointing to or picking up medications) were incorporated into the transcripts.

Evaluation of Misuse

Three pharmacists with clinical experience working with the geriatric population comprised a misuse analysis team. Prior to the misuse evaluation, information about the participant and OTC medication selected was de-identified and entered into Redcap. This information included participant’s self-reported medication list and health conditions, and the selected OTC and reported OTC use (which included direct portions of the interview transcript and use summaries prepared by the research team). Data were extracted from the transcripts in this manner to ensure that the misuse analysis team would be unable to identify whether the interview occurred before or after Senior Section implementation. Also included were photographs of the OTC medication (front, back, and top to capture all product labeling information) as reference for the misuse analysis team. A random number generator was applied to the participant list, which randomly assigned all participants to three different batches for evaluation. The overall process of randomization and blinding ensured that the misuse analysis team would be unable to identify whether the interview occurred pre- or post-implementation. Misuse was first evaluated independently by each reviewer, and responses were then consolidated in preparation for group discussion and discrepancies between reviewers were noted. The misuse study team, supported by study researchers then met as a group to review independent comments, facilitate discussion about discrepancies (which were commonly the result of misuse analysis team members’ interpretation of the drug facts information on the label or what patients meant when describing their use), and achieve consensus about final misuse classifications.

Four misuse outcomes were operationalized by the misuse analysis team through these group discussions:

For Drug-Age, Drug-Disease, and Drug-Label misuse, the final determinations were based on evaluations and agreement by the misuse analysis team, and was measured as the frequency of misuse per participant.

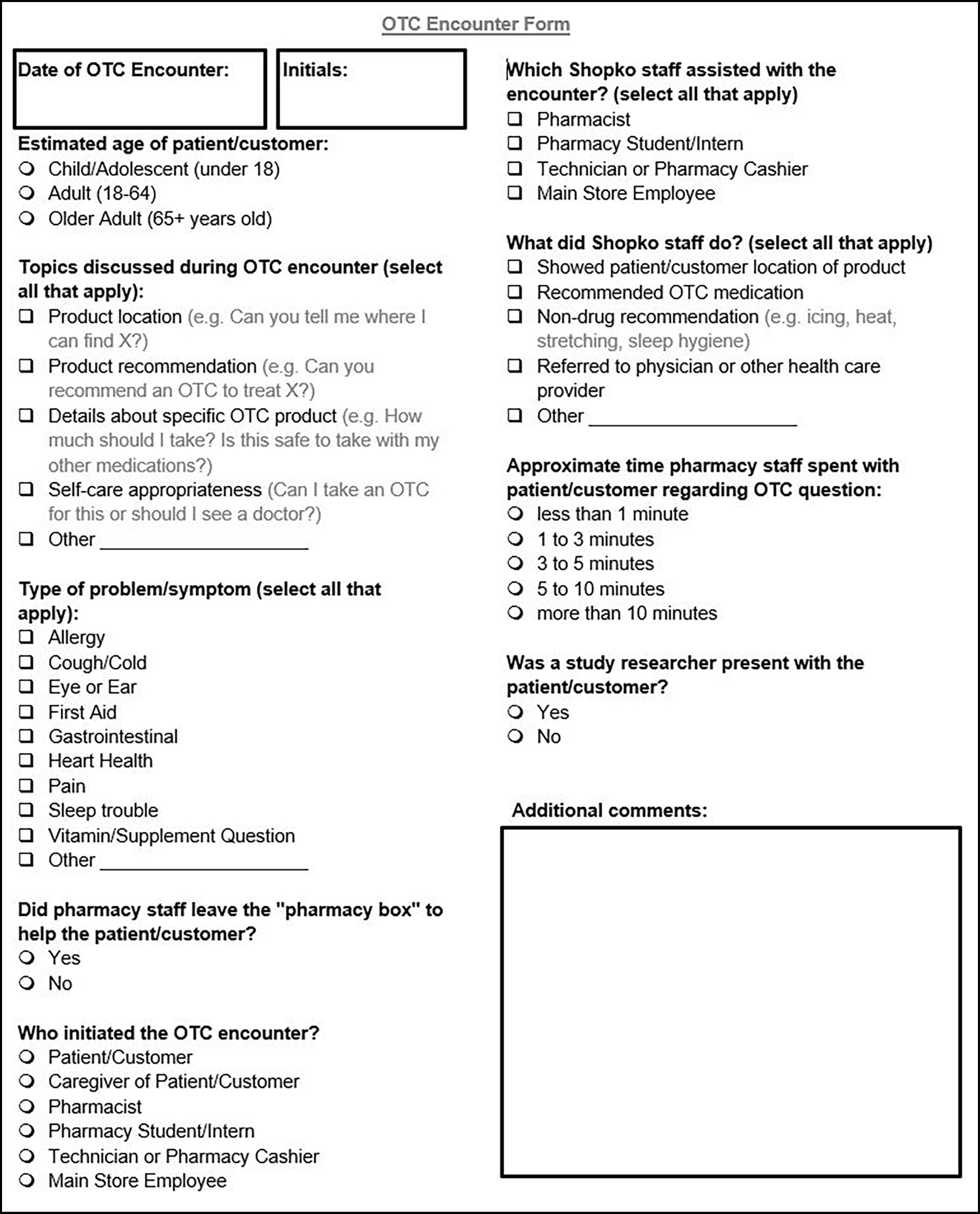

OTC Encounter Form

The purpose of the Pharmacist OTC Encounter Form was to:

The encounter form was used to collect recommendation characteristic outcomes that are in addition to the OTC medication misuse outcome (e.g., referral to a physician, behavioral or medication recommendations). Further, the encounter form was used to quantify the time required to interact with consumers before and after the intervention is implemented. Encounter form data was collected at both baseline and post-intervention.

Published

Gilson A, Xiong KA, Stone JA, Jacobson N, Phelan C, Reddy A, Chui MA. Improving Patient-Pharmacist Encounters with Over-the-Counter Medications: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Study. Innovations in Pharmacy. in press.

Gilson AM, Stone JA, Reddy A, Chui MA. Exploring how pharmacists engage with patients about over-the-counter medications. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(6):852-856.

Reddy A, Lester CA, Stone JA, Holden RJ, Phelan CH, Chui MA. Applying participatory design to a pharmacy system intervention. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(11):1358-1367.

Chui MA, Stone JA, Holden RJ, et al. Improving OTC medication safety through a refined system redesign intervention in a community pharmacy. Innov Aging. 2018;2(Suppl 1):82. eCollection 2018 Nov.

Chui MA, Holden RJ, Russ AL, Abraham O, Srinivas P, Stone JA, Jahn MA, Ozkaynak M. Human Factors in Pharmacy. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 2017;61(1):666-670.

Chui MA, Stone JA, Holden RJ. Improving over-the-counter medication safety for older adults: A study protocol for a demonstration and dissemination study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(5):930-937.

Gilson AM, Stone JA, Morris AO, Brown RL, Xiong KZ, Jacobson N, Holden RJ, Albert SM, Phelan CH, Walbrandt Pigarelli DL, Breslow RM, Welch L, Chui MA. Impact of a pilot community pharmacy system redesign on reducing over-the-counter medication misuse in older adults. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2021 Apr 15.

Xiong KZ, Shah S, Stone JA, Jacobson N, Chui MA. Using a scenario-based hybrid approach to understand participant health behavior. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021.

Gilson AM, Xiong KZ, Stone JA, Jacobson N, Chui MA. A pharmacy-based intervention to improve safe over-the-counter medication use in older adults. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021 Mar;17(3):578-587.

Shah S, Gilson AM, Jacobson N, Reddy A, Stone JA, Chui MA. Understanding the Factors Influencing Older Adults’ Decision-Making about Their Use of Over-The-Counter Medications-A Scenario-Based Approach. Pharmacy (Basel). 2020 Sep 18;8(3).

Peer-Reviewed Research Podium/Oral Presentations and Abstracts

Chui MA, Bix L, Holden RJ, Albert S. “Optimizing OTC Medication Use: Packaging, Human Factors, Pharmacy Redesign” the Gerontological Society of America, November 2018

Reddy A, Stone JA, Chui MA. “How do health literacy and risk perception impact older adult misuse of over-the-counter medications?” Midwest Social & Administrative Pharmacy Conference, August 2018

Peer-Reviewed Research Podium/Oral Presentations and Abstracts

Shah SR, Morris AO, Stone JA, Chui, MA. “Older Adult Shopping Persona Types and its Impact on Over-the-Counter Medication Misuse” Accepted to International Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care, March 2020 (conference canceled).

Chui MA, Gilson A, Stone JA, Morris AO, Brown R, Holden RJ, Jacobson N, Albert S, Xiong KZ, Phelan C, Walbrant-Pigarelli D, Breslow, R. “ Impact of a community pharmacy system redesign on reducing over-the-counter medication misuse in older adults” Accepted to American Pharmacist Association Annual Meeting and Exposition, March 2020 (conference canceled).

Reddy A, Lester CA, Stone JA, Phelan C, Chui MA. “Using invisible design to engage stakeholders in health system intervention implementation.” Academy Health Dissemination & Implementation Conference, December 2019

Reddy AC, Chui MA. “The Relationship Between Health Literacy, Risk perception, and Over-the-Counter Medication Misuse”. Presented at Wisconsin Health Literacy Summit, April 2019.

Reddy AC, Chui MA. “Impact of Health Literacy and Risk Perception on Over-the-Counter Medication Misuse”. Presented at Translational Science, March 2019.

Flynn B, Xiong KZ, Stone JA, Chui MA. “A Comparison of Patient Encounters Prior to and After an OTC Safety Intervention in a Community Pharmacy Setting” American Pharmacists Association Annual Meeting, March 2019

Reddy A, Stone JA, Chui MA. “Utility of Invisible Design in Developing a Pharmacy System Intervention” Human Factors & Ergonomics Health Care Society Symposium, March 2019

Xiong KZ, Reddy A, Stone JA, Lester CA, Chui MA. “Using Implementation Outcomes to Guide Stakeholder Engagement in an Over-the-Counter Medication Safety Intervention” Academy Health Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation, December 2018

Reddy A, Stone JA, Lester CA, Holden RJ, Chui MA. “Developing a System-level Medication Safety Intervention for Older Adults: The Utility of Participatory Design. National Academy of Engineering, May 2018

Reddy A, Stone JA, Lester CA, Holden RJ, Chui MA. “Using Participatory Design to Develop a Pharmacy-Based Intervention to Improve Over-the-Counter Medication Safety for Older Adults” American Pharmacists Association Annual Meeting, March 2018

Lester CA, Reddy A, Jamie Stone, Holden RJ, Chui MA. “Participatory Design: An effective approach to designing a patient-centered intervention to Improve Over-the-Counter medication safety for older adults” Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, June 2017