School of Pharmacy Associate Professor Jason Peters has patented novel genetic tools to accelerate biofuel production

By Nicole Etter

Biofuel production has a surprising key ingredient: bacteria. These microbes devour plant material, like leaves and stems from native plants, and convert it into biofuels and bioproducts. But in the process, the deconstructed plant material releases toxins that get in the way, creating one of the challenges to making biofuels an efficient and economical alternative to existing fuels.

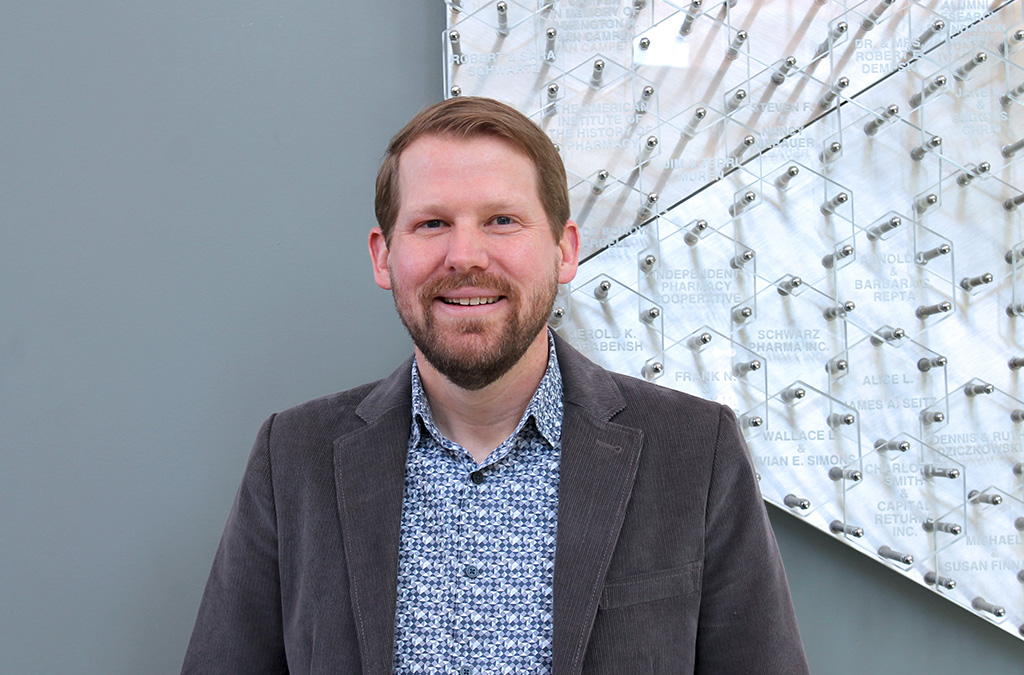

“Toxins can inhibit the growth of the bacteria, and then the bacteria don’t produce as much biofuel or bioproduct,” explains Jason Peters, associate professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy and co-investigator with the U.S. Department of Energy Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE GLBRC).

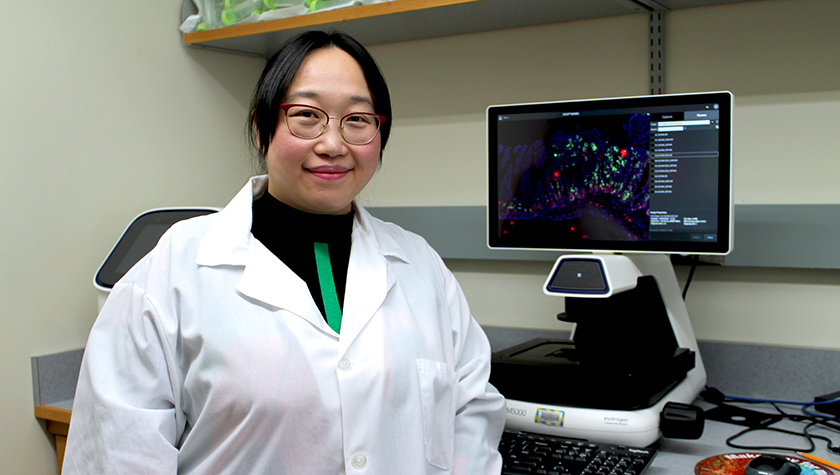

To surmount this barrier to making biofuel production commercially viable, Peters and Peters Lab Scientist Amy Banta recently patented genetic tools, including a Mobile-CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) system and synthetic promoters, to control gene expression in Zymomonas mobilis, a bacteria used in biofuel production.

“Ultimately, if we want to make the kind of specific discoveries that are going to drive the field forward, we’ve got to get into the organisms that are truly relevant, not only for bioenergy but for human health.”

–Jason Peters

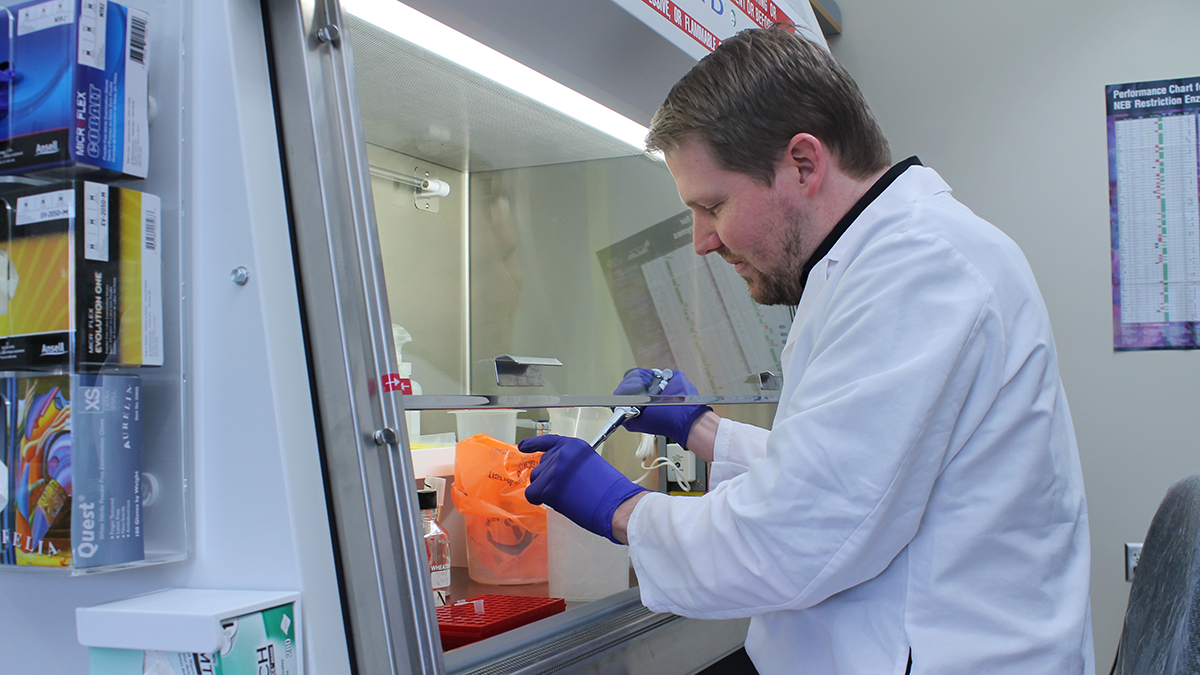

Peters co-developed the Mobile-CRISPRi technique in 2019. Whereas the CRISPR system cuts DNA to edit genes, CRISPRi instead prevents targeted genes from turning on. Originally, this gene-muting tool had to be built for each bacterial species, but Mobile-CRISPRi solved that problem by packaging the tool into a genetic element that can move between bacteria, allowing researchers to apply the system across species without re-engineering each one.

The technology allows the Peters Lab to identify and engineer genes that make the bacteria more resistant to the toxins, using the CRISPRi system to turn some genes “down” and synthetic promoters to turn other genes “up.”

“We can change the expression in a very fine-tuned way, whenever we need it,” Peters says.

That has the potential to improve the efficiency of producing biofuels like isobutanol and other valuable bioproducts — for example, specialty lipids for cosmetics.

“The idea that we can make bioproducts from these bacterial strains in addition to biofuels puts us in a better position to be viable in the energy market,” he says.

Their patent is for a new CRISPRi version optimized for Zymomonas mobilis, which leverages synthetic promoters as a unique and powerful approach.

“We don’t totally understand the rules that allow the promoters to work across different organisms, but we’ve designed this synthetic set and we’re able to deploy them using the same technology behind Mobile-CRISPRi, and then we can test their activity,” Peters explains.

In addition to studying Zymomonas mobilis, the Peters Lab is working with another industry-relevant bacteria called Novosphingobium aromaticivorans, or “Novo” for short. The recently patented technology could also be helpful to optimize that organism to produce bioproducts.

“For Novo in particular, it can actually consume some of the toxins,” Peters notes. “So at a low concentration, those toxins are food for it, but at a high concentration, they will kill the bacteria.”

The work is supported by the DOE, which funds four Bioenergy Research Centers nationwide, including the GLBRC. Since 2007, the centers have collectively registered more than 1,000 inventions — including the latest patent by Peters and Banta, who also have another patent application related to novel CRISPR tools pending.

“The federal government has the resources for us to make these kinds of discoveries and really push the boundaries on the research,” Peters says. “The DOE is supporting a nationwide infrastructure for understanding these sorts of problems, and that’s something that wouldn’t be possible to replicate in any other way.”

And biofuel could be just the beginning. The new genetic tools could also have applications for other research areas, including combating antibiotic resistance in pathogens.

“We’re using those tools in a lot of different contexts now, and they do seem to be generally useful across many different organisms, not just ones that are relevant for bioenergy,” Peters says.

“If we develop the tools and put them out there for people to use, then we can accomplish much more than we would be able to with just our own hands — we could get closer to all the genes and all the bacteria.”

–Jason Peters

While some researchers might be content with proof-of-concept studies using common lab strains of bacteria, Peters prefers to work with the bacterial strains that are most applicable to solving real-world problems — even if it’s more challenging. On his office wall is a poster, designed by a student, that sums up his lab’s aspirational philosophy: “All the genes and all the bacteria.”

“Ultimately, if we want to make the kind of specific discoveries that are going to drive the field forward, we’ve got to get into the organisms that are truly relevant, not only for bioenergy but for human health,” he says.

Peters is known for his expertise in developing CRISPR tools, and he has made those tools available to other researchers through repositories such as Addgene. He tracks the requests for his CRISPR tools that are encoded in physical DNA — now numbering more than 600 requests from around the world. He doesn’t know how the tools are being used by the requesting researchers or their collaborators, but he’s excited about the possibilities.

“If we develop the tools and put them out there for people to use,” he says, “then we can accomplish much more than we would be able to with just our own hands — we could get closer to all the genes and all the bacteria.”

This material is based upon work at the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research under Award Number DE-SC0018409.