Associate Professor Jason Kwan launches a new course to help undergraduates explore soil microbes and build hands-on skills in bioinformatics

By Brianna Foth

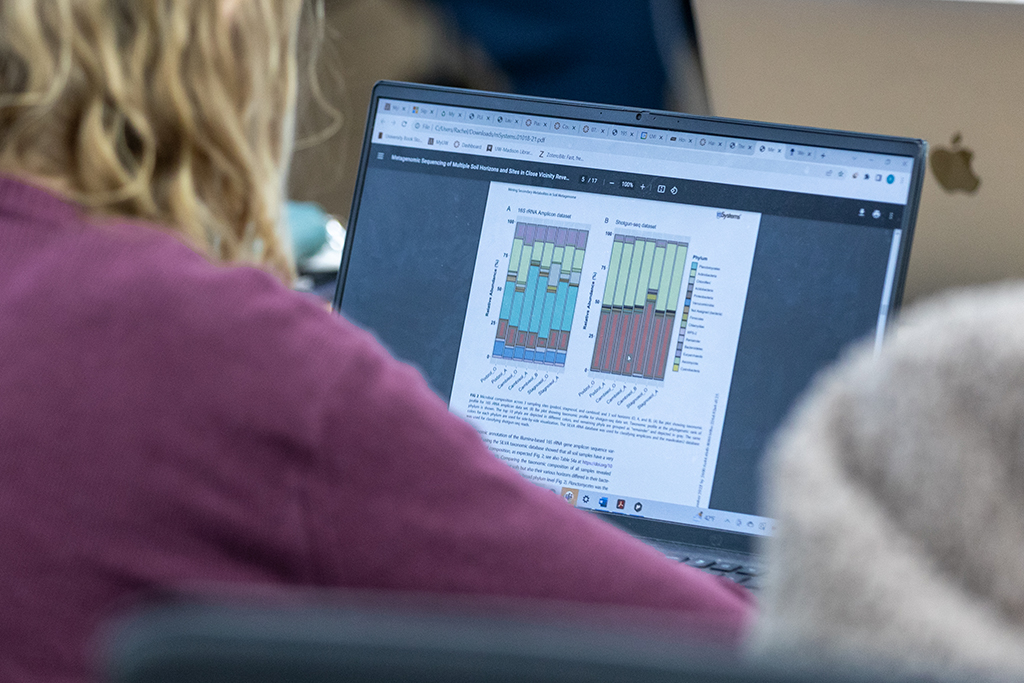

In a studious corner of College Library on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus, five students type away at their laptops near the front of a glass-walled classroom. They’re working through an exercise that requires them to calculate the diversity of two “communities” of organisms using the Shannon index — a complicated-looking, but computationally straightforward formula often used in ecology research. On the projector screen in front of them is a visual of the two “communities” they’re analyzing: a colorful cast of Pikachus, Charmanders, Bulbasaurs, and Squirtles — characters from the popular video game franchise Pokémon.

“A lot of people go into college intending to study STEM subjects, but only a fraction of those students actually graduate in those areas — so there’s something happening along the way that’s discouraging people,” says Jason Kwan, associate professor in the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Pharmaceutical Sciences Division. “Introductory STEM courses can sometimes be quite dry and uninspiring on the surface. My goal is to make those seemingly dry subjects more accessible and exciting.”

“We wanted to let the students have some ownership over what they were doing, which is why we opted for them to learn through discovery.”

—Sam Waterworth

In pursuit of that goal, in 2019, Kwan began developing a new undergraduate course with the help of Sam Waterworth, then a postdoctoral research associate in the Kwan Lab. The course, Tiny Earth Genomics, was taught for the first time in spring 2022 and follows the model of the global Tiny Earth Initiative, run by Wisconsin Institute for Discovery Director Jo Handelsman, which engages undergraduate students in research involving the discovery of antibiotics produced by soil microbes.

What makes Kwan’s course unique is its focus on teaching students cutting-edge data analysis methods and basic principles of bioinformatics and genomics, all while guiding them through a hands-on research project for which the students will design their own research questions and carry out independent investigations.

“We’re hoping to give students the experience of undertaking research and taking ownership over a project,” says Kwan. “We prepare data for them, and then we allow them to examine the data, come up with research questions, and conduct the project how they would like and answer the questions that they want to answer. It’s really about fostering scientific inquiry, curiosity, joy, and discovery.”

Adding to a global network

The global Tiny Earth network, whose center lies at the Handelsman Lab at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, consists of a shared curriculum taught to more than 10,000 students in 27 countries each year.

Kwan began developing the course as part of a Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) award he received from the National Science Foundation in 2019, which supported his lab’s development of new bioinformatics approaches to explore the formation and ecology of microbial communities. But the grant also has an emphasis on integrating research and education, so Kwan used the opportunity to help Tiny Earth grow.

One of the main goals of the genomics course, says Kwan, is to offer an opportunity to engage in real-world research to students who might otherwise be hesitant to apply to a lab.

“It takes a lot of confidence to approach a professor and ask if there is a place in their research lab,” says Kwan. “Getting involved with research requires a lot of initial effort, and there’s a finite number of labs on campus at any one time that can take on students. We’re fortunate that we are a major research university, and there are lots of opportunities, but not everyone is able to find those opportunities.”

To assist with designing and later teaching the course, Kwan recruited Waterworth, who was then in the process of completing a teaching certificate through UW–Madison’s Delta Program in Research, Teaching and Learning. Her experience with teaching was instrumental in helping design the course’s syllabus and activities, Kwan says.

“Sam was very helpful when it came to designing the syllabus and thinking about activities that would actually be instructive and helpful for learning,” says Kwan. “I’ve learned a lot from her example.”

For her role in the creation of the course, Waterworth was recently honored with a Postdoc Excellence Award — one of just three accolades awarded by the UW–Madison Postdoctoral Association to postdocs who have made outstanding efforts in the areas of teaching, service, and mentoring.

“That was very exciting and I was very honored,” says Waterworth. “The Postdoctoral Association does some awesome stuff and is a great resource for all UW postdocs. I was exceptionally happy that they thought my work merited the award.”

Engaging in real-world research

Some of the main goals of the Tiny Earth Genomics course include teaching students how to navigate genomic databases to find needed information and data, how to use available bioinformatic tools and interpret results, how to formulate and test their own research questions and hypotheses, how to interpret data and draw conclusions, and how to communicate their research design and results.

“We wanted to let the students have some ownership over what they were doing, which is why we opted for them to learn through discovery,” says Waterworth. “This, we feel, also helps the student develop their natural curiosity and channel it through scientific rigor to develop something entirely unique.”

For the first five weeks of the course, students learn background concepts in metagenomics — the study of genetic material recovered via culture-independent sequencing — and they study how scientific papers are written and interpreted. Afterward, they begin their research projects.

“For the projects, we present the students with some pre-processed data that’s publicly available,” says Kwan. “But the thing is, with metagenomics, the data is so multi-dimensional that even if someone has already done a study on it, there will be questions that are still unanswered. So, students will read the papers that these datasets are based on and will think about research questions and hypotheses that could be answered with the data that is available. And then they’ll design their project and start their investigation; we’re there to help out and guide them, but ultimately, they are the ones that decide the direction of the project.”

But while the course helps students gain important skills in independent research and data analysis, it also teaches them foundational knowledge in metagenomics, which is a main research focus of the Kwan Lab.

“A lot of my papers are concerned with assembling the individual genomes of symbionts and other bacteria to see what they do, how they evolved, and what sort of small molecules they make,” Kwan says. “It’s made it sort of challenging to teach in a way, because a lot of this stuff is very routine for us. And figuring out how to make some of these concepts accessible to students who have no experience with them was very challenging, but also very gratifying.”

Looking ahead

After experimentally teaching the course for a full semester, Kwan and Waterworth were pleased with what their students achieved with their research projects and eager to receive feedback from students about what worked well and what they could improve.

“As this was the first iteration of the course, we asked the students to fill out a somewhat informal questionnaire about what they liked, didn’t like, what was useful, and what wasn’t, which we used to inform the development of this new iteration,” says Waterworth. This semester, for example, the course features more interactive or gamified activities to help students study the materials.

Having found success with the course, the two are looking forward to seeing where students go after completing the course.

“I’ve heard from a number of students who are going on to take graduate courses in areas of healthcare, including pharmacy,” says Kwan. “Some of them have even asked me for letters of recommendation.”

But most of all, they are proud to have helped students become more aware of the increasingly important role of bioinformatics in research and hopefully helped them develop skills that will continue to benefit them in their careers and beyond.

“The way I see it, a lot of modern research areas are getting more involved in this sort of high-dimensional data analysis,” says Kwan. “So, hopefully, this course shows people that there is an intersection between computation and research, because it could interest all sorts of different students — I envision computer science students maybe being interested in it, as well as people coming from the biological sciences or physical sciences. So I’m hoping this will increase literacy and competency in these kinds of areas, or at least stimulate people’s interest.”

And soon, they hope their curriculum touches more students around the world, through the global Tiny Earth Network.

“What I’m most excited about for the future of this course is that it may get some more students into the very exciting field of bioinformatics,” says Waterworth. “With luck, our curriculum will start being distributed to other universities via the network of Tiny Earth Partner Instructors. Then there will be new, young bioinformaticists all over the world.”