12

September

Development of the Rural Pharmacy Practice course serves as a national model

By Iseult Gillespie

Nearly a third of Wisconsinites live in rural areas, where there might be just one primary care provider and one pharmacy serving the entire community.

“How can we train our student pharmacists to collaborate effectively with the primary care team and develop services that enhance patient care across rural communities?” asks Ed Portillo (PharmD ’14), assistant professor in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Pharmacy Practice Division.

He sought to answer that question with the School’s Rural Pharmacy Practice concentration in the PharmD program, which was introduced in the Fall 2019 semester.

“The heart and soul of this program is finding out how we can get practitioners with different skill sets and backgrounds in these rural communities talking,” he says.

Alongside colleagues at the School, Portillo recently collaborated with a team to design the concentration’s pioneering curriculum using the Taba model of learning and design and co-authored an article about the process, recently published in the journal Innovations in Pharmacy. This is the first time that the Taba model has ever been applied to a pharmacy program.

Named after the education reformer Hilda Taba, the Taba model is a model of curriculum design that connects theory to practice. By encouraging participants to draw on their own experiences and connect learning to the world around them, Taba brings the needs of students, instructors, and the communities they serve to the fore. Rather than a standard curriculum design — which typically builds a course around a set of predefined learning objectives — Taba curriculums are designed to push learning beyond the classroom.

“The heart and soul of this program is finding out how we can get practitioners with different skill sets and backgrounds in these rural communities talking.”

—Ed Portillo

The model boils down to three main things, says Portillo: It’s inspired by the people doing the work, it’s collaborative, and it focuses on experiences.

“That’s the spirit of the Taba model,” says Portillo. “It’s getting at the experiences, and not just learning about public health topics but applying them and seeing them in rural communities.”

Applying Taba to improve practice

The School of Pharmacy is one of few schools in the country with a rural health program. For the curriculum designers, Taba provides an exceptional model for community engagement that a rural health program requires.

To build a truly comprehensive rural pharmacy curriculum, “you need to engage with stakeholders who are currently involved in advancing rural healthcare, both outside of the School as well as within the School,” Portillo says. The Taba model embodies this spirit of grass-roots collaboration to inform the curriculum design process, which has resulted in coursework emphasizing hands-on, real-world application of students’ clinical skillset to fit the setting of rural communities.

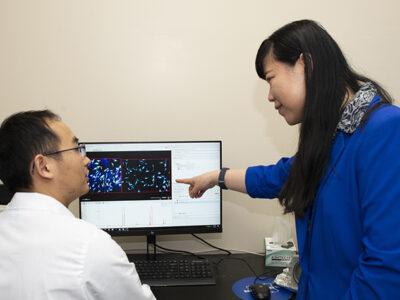

“We wanted to consider what would help meet the changing needs of healthcare in rural areas, which are evolving especially quickly during this pandemic,” says Kevin Look (PharmD ’09, PhD ’13), assistant professor in the School’s Social and Administrative Sciences Division, who help develop the concentration.

In designing the curriculum, Portillo and Look also tapped the expertise of Professor David Mott (BS ’88, MS ’92, PhD ’95), chair of the Social and Administrative Sciences Division and William S. Apple Distinguished chair; and Associate Professor Robert Breslow (BS ’75), co-director of interprofessional education Associate Professor Casey Gallimore (PharmD ’05, MS ’13), and Assistant Dean and Professor Mara Kieser, all of the Pharmacy Practice Division.

School of Pharmacy alumni who serve patients in rural areas of the state were also heavily engaged throughout the curriculum design process.

“Most of the rural pharmacists in Wisconsin are graduates of the School of Pharmacy, which gives us a strong connection to the rural areas of the state that we want to open up to our students,” says Portillo.

The result of this strong alumni pharmacist involvement is a rural health curriculum designed to teach students how to apply their clinical skills to collaborate with patients and meet the specific needs of rural communities.

School of Pharmacy faculty have devised a unique application of the model that allows students to “incorporate their clinical skillset and rural healthcare interest by partnering with rural communities to co-create innovative healthcare services,” says Portillo. “Our goal is to teach our students how to be effective rural community members, servant leaders, and healthcare practitioners, with the goal of partnering with the community to develop healthcare programs that are really fitting to that group.”

PharmD students can participate in the Rural Pharmacy Practice option in their third year, which is their final year of didactic coursework before they move into clinical rotations. Look says that the Rural Pharmacy option can be a very effective transition between the two years, given the heavy experiential component and the required longitudinal project to improve rural health services.

During the course, instructors assign journal articles and other educational materials to students, before bringing in speakers who have applied that content to real-life situations. Later in the course, students are placed in rural communities, where they conduct interviews with pharmacists and public health officers. They also document the work of rural healthcare through journals and photo diaries. At the end of the course, students are required to pitch a service that helps fulfill an important local need.

“Students are not coming into those communities with all the answers — in fact, it’s the opposite,” says Portillo. “We really emphasize that if you are going to be an innovator, you have to be a collaborator.”

The course design expands channels of collaboration with many School of Pharmacy alumni, who work in rural pharmacies across the state. “We are connecting with many of our alumni who are trailblazers and innovators in rural practice,” says Portillo. “We have been very fortunate that they have joined our team,” says Portillo.

Setting a national example

The team’s application of the Taba model has been of interest to pharmacy schools nationwide. Portillo and colleagues documented their groundbreaking application of Taba in their article, published in Innovations in Pharmacy.

Titled “Intentional Application of the Taba Curriculum Model to Develop a Rural Pharmacy Practice Course,” the article offers a framework for community engagement and optimizing rural healthcare practice through the case study of the School of Pharmacy’s course. The article has been positively received, with more than 130 downloads to date.

“We really emphasize that if you are going to be an innovator, you have to be a collaborator.”

—Ed Portillo

Look says they will continue to “share the successes we’ve had to change education more broadly. Even here at UW, I think it’s already making us more engaged with alumni and stakeholders.”

In future, the Rural Pharmacy Practice course designers will continue to gather detailed participant feedback and adapt course content to address pressing contemporary needs. For instance, their application of the Taba model has made the course particularly flexible in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Look says that it has been “a fairly seamless transition” to online learning. Guest speakers can connect with students via video conferencing rather than traveling from outside areas, and the course can now incorporate the perspectives of rural pharmacists from further afield who wouldn’t have been able to visit in person.

As the course continues to develop, its designers and instructors look forward to forging new connections between the School and rural communities. Portillo believes their application of the Taba model of learning will provide student pharmacists with the skills and sensitivities to “be future leaders in rural healthcare innovation while providing exceptional care to patients across all areas of the state.”