School of Pharmacy Assistant Professor Quanyin Hu and the research team publish in Nature Communications on an innovative use of hydrogels to deliver a suite of therapeutics that turbocharge the body’s immune response to cancer cells

By Will Cushman

This article originally appeared on UW–Madison’s news page.

Cancerous tumors that aren’t candidates for surgery or chemotherapy sometimes respond well to alternatives like immunotherapy, but even cutting-edge cancer treatments that harness the immune system have their limits.

A recent study by researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison points toward a potential new approach for pushing the limits of immunotherapy, opening a door to more effective treatment of inoperable tumors and metastatic cancer.

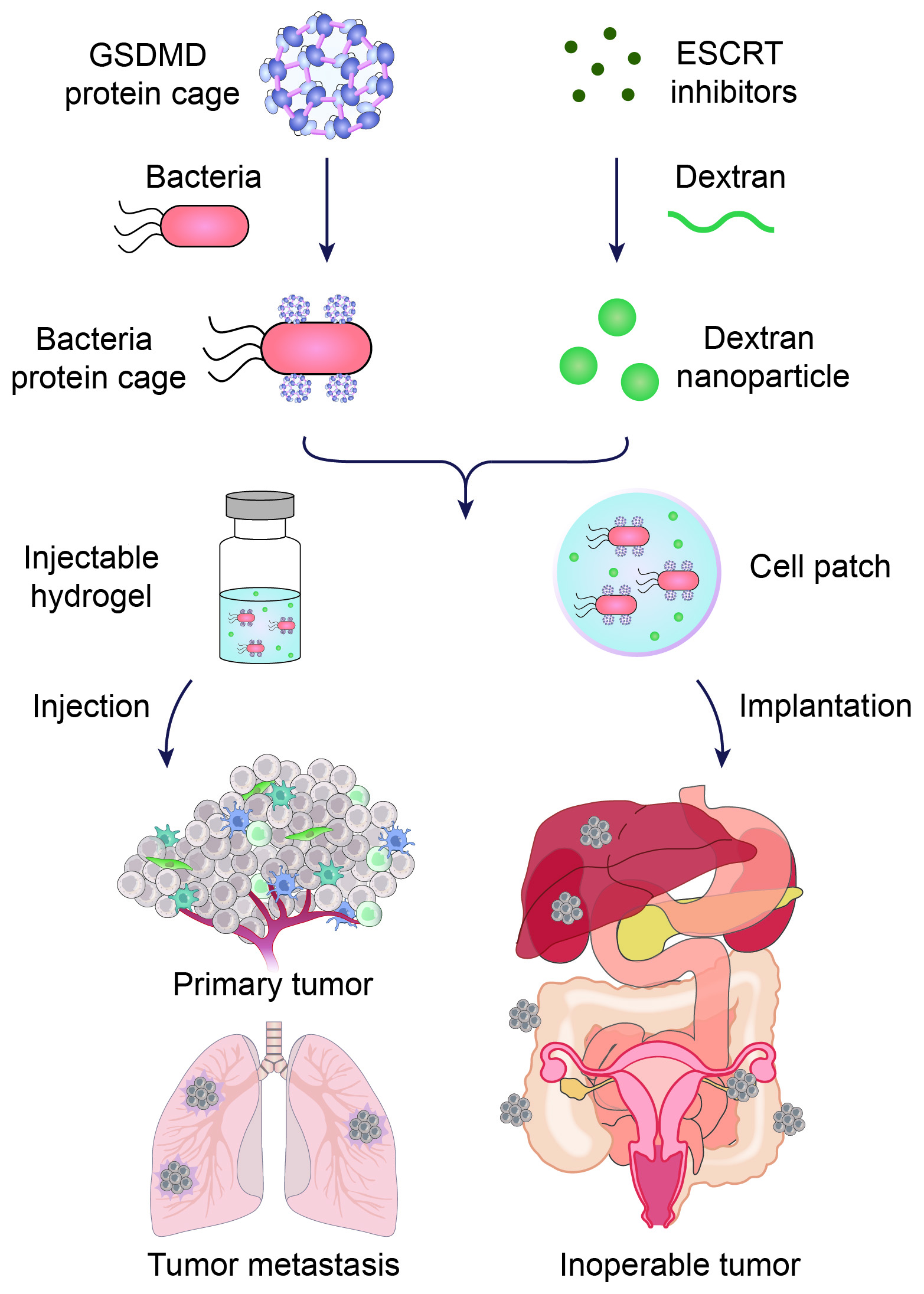

Published in October in the journal Nature Communications, the approach relies on hydrogels or patches, depending on the location and type of the tumor, to deliver a suite of therapeutics that turbocharge the body’s immune response to cancer cells.

Led by Quanyin Hu, a professor in the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy, the research builds on Hu’s previous development of hydrogel drug delivery systems and advances in the understanding of a unique type of cell death called pyroptosis.

Cell death plays an important role in cancer and its treatment. While normal cells eventually die and are replaced by new cells, cancer cells ignore the body’s signals to self-destruct, leading to uncontrolled growth into tumors that can spread around the body.

Enter pyroptosis. Because this form of cell death is so highly inflammatory, scientists believe pyroptosis is an immune response to invading microbes and other pathogens. In recent years, they’ve also shown pyroptosis may be a powerful tool for killing cancer cells. This is because pyroptosis leads cells to expel their contents, including cancer-related antigens that the body’s immune system can then target.

“We are excited about pyroptosis because it can trigger the release of intracellular contents, as well as tumor-associated antigens, and elicit a strong immune reaction,” says Hu.

Researchers must overcome significant hurdles, however, to effectively harness pyroptosis against tumors. Most significant is overcoming the ability of tumor cells to repair themselves during pyroptosis, which dampens the immune system’s ability to detect and destroy the cancer.

“Cancer cells always have a self-defense system,” says Hu.

In the case of pyroptosis, a protein complex known as ESCRT III swoops in to repair a damaged cell’s membrane and stop the cell’s death. When a cell is cancerous, this means ESCRT III’s repairs prevent immune cells from detecting and attacking antigens associated with the tumor that spill out during pyroptosis.

To overcome this problem, the drug delivery system Hu devised provides a one-two punch of therapeutics to initiate pyroptosis in cancer cells and then keep those cells from repairing themselves.

First, Salmonella bacteria are outfitted with a specific protein called Gasdermin D, which kickstarts pyroptosis. The bacteria enter cancer cells, allowing Gasdermin D to initiate the inflammatory cell death process, and attract powerful immune cells to attack the tumor.

To ensure that pyroptosis persists, the delivery system also includes molecules that inhibit the ESCRT III protein complex responsible for repairing the cancer cell’s membrane.

These short-circuiting molecules are encapsulated within nanoparticles that are specially designed for the microenvironment around tumors, which is more acidic than noncancerous tissue. The acid slowly breaks down the nanoparticles, allowing for a gradual and sustained release of the crucial molecules.

Together, the bacteria, Gasdermin D proteins and nanoparticles turn “cold” tumors “hot,” meaning the tumors become susceptible to attack by immune cells.

Hu and his colleagues tested the dual-drug system in two formulations — an injectable hydrogel and an implantable hydrogel-based cell patch — in mouse models representing advanced, inoperable cancers including metastatic breast cancer, melanoma, and inoperable ovarian cancer. The cell patches were implanted next to inoperable tumors, while the hydrogel injections targeted other primary and metastatic tumors.

The results were promising. Mice that received the treatments mounted local and systemic immune responses against their cancer tumors, inhibiting tumor growth and spread and prolonging their lives.

“That’s really exciting for me,” says Hu, though he acknowledged that more research was needed to understand any potentially negative long-term effects of the bacteria used in the treatment. Production and storage of the hydrogels also need to be streamlined and improved for the treatment to become practical.

Still, Hu is enthusiastic about the approach, particularly about the possibility of better tailoring immunotherapy based on a patient’s needs.

The hydrogels could be injected around tumors or in the space left following a tumor’s removal during surgery. Meanwhile, the hydrogel-packed cell patches use materials that are already commonly available and approved for medical devices.

“We can customize our delivery platform to work in different application scenarios,” says Hu.