School of Pharmacy team creates a responsive, patient-focused video game for cancer education and prevention among teens

By Katie Ginder-Vogel

Imagine being a high schooler and receiving the news that your mother has been diagnosed with breast cancer — as more than 280,000 women are annually in the U.S. The doctor shares that it’s stage 3 cancer and that treatment will begin very soon.

But your mind swirls with questions: What does stage 3 mean? Why did she get it? How is it treated? Will I develop it, too?

This is one of three scenarios covered in a new educational game being developed by Olufunmilola Abraham (MS ’11, PhD ’13), assistant professor in the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy’s Social and Administrative Sciences Division.

“All of the questions we’re trying to answer in the game are based on focus groups and a cancer awareness study with hundreds of teens in Wisconsin,” says Abraham. “We’ve taken all that information — what do cancer cells look like? What does treatment mean? — and built that into the content of the game.”

“My passion is community engaged research, and what that means to me is taking the time to talk with my community, teens, patients, youth, and families to understand how they want to learn and receive health or medication-related information.”

—Olufunmilola Abraham

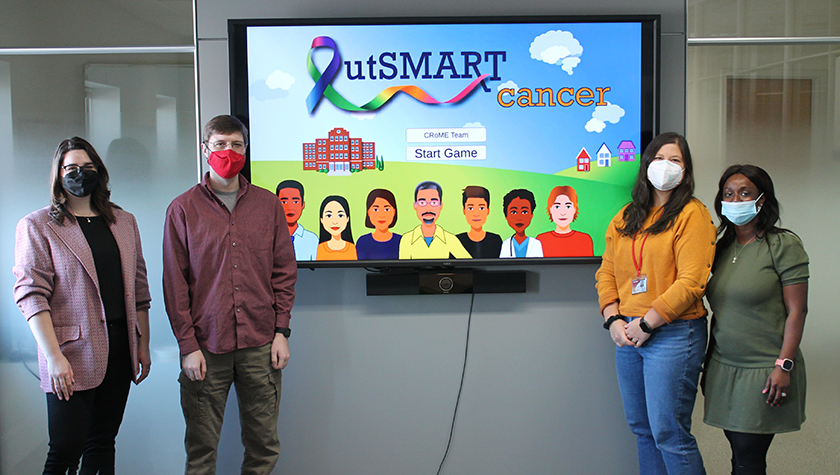

The new game, OutSMA℞T Cancer, is based on Abraham’s extensive research on youth perceptions of cancer and cancer prevention and funded through a grant from the UW Carbone Cancer Center and the American Cancer Society. School of Pharmacy information processing consultants Eric Robinson and Sally Griffith-Oh are working with Abraham to design and build the game, which Abraham hopes will be accessible and engaging.

“Serious games, which are games for education rather than entertainment, are engaging, active learning tools,” says Abraham. “They have the potential to reduce disparities in terms of accessibility and understanding of information by making the topics less intimidating.”

Incorporating youth perspectives

Using real-life stories, the goal of OutSMA℞T Cancer is to educate teens about cancer screening, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment, as well as the important role of family support and the role of genetics. A key aim is to facilitate early screening and treatment.

The game’s learning outcomes were developed using the UW Carbone Cancer Center’s Cancer Clear and Simple curriculum and adapted with feedback from focus groups with teens around Wisconsin, a nationally representative youth advisory board, and the School of Pharmacy’s students.

“The curriculum is simple to understand, and there are multiple versions for different cultural groups,” says Abraham.

“But Clear and Simple wasn’t designed for teens, so we’ve done the work interpreting it for teens ages 12 to 18, to help them make healthy choices and support family members who need to get screened or treated for cancer.”

Abraham’s research group spent months traveling to middle and high schools around Wisconsin to hear from students what they already know about cancer, what they needed to know, and how they wanted to learn it, which led to three publications in JMIR Serious Games, the Journal for Cancer Education, and Cancer Control.

“My passion is community engaged research, and what that means to me is taking the time to talk with my community, teens, patients, youth, and families to understand how they want to learn and receive health or medication-related information,” says Abraham.

Through focus groups, Abraham learned that customizable characters and realistic storylines are important elements, and that gameplay should focus on preventive behavior.

Additional feedback came from Abraham’s research group, which includes PharmD students. The game development team met biweekly to discuss how the game should look and function, and the entire team contributed to the project.

“Evan Slonac, a first-year PharmD student, has been wonderful and was really instrumental in providing a youth perspective,” says Abraham. “Research specialists Lisa Szela and Claire Rosenberger dedicated two years of work to the game. Eric Robinson played a crucial role in developing the game, and Sally Oh-Griffith created graphics, images, and a logo.”

Robinson is handling the entirety of coding the game, programming it in a game engine called Unity 3D, which he used to complete Abraham’s first game built at the School of Pharmacy, MedSMA℞T, about youth opioid education. MedSMA℞T has evolved into MedSMA℞T Families, which combines the game and personalized family medication safety plans, and is slated to be deployed in three health systems by early next year.

“Unity makes it easy to build it out to different platforms, and the team specifically wanted this game to work on mobile, based on feedback from MedSMA℞T,” says Robinson. “Making sure it’s mobile-friendly in terms of its design is at the front of every decision I’m making.”

Game play

The game is an interactive story, or visual novel, in which the player chooses their own path, although they are ultimately routed to the correct information. Simple text walks the player through the game.

“To make the game playable and engaging, we are forced to make information intuitive and easy to understand to reinforce learning,” says Abraham. “Users can go at their own pace and play the game until they understand what they need to get out of it.”

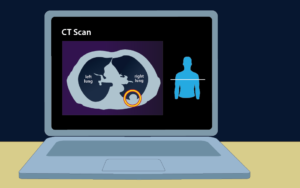

In addition to the breast cancer scenario, another path in the game is set at school and addresses the prevalence of vaping among young people and the risk of lung cancer vaping poses. In a third scenario, the player’s father receives a colon cancer screening reminder, and the player learns about cancer prevention tools, the role of genetics in cancer, and why cancer screening is important.

“It’s a resource that could be used in a classroom or a doctor’s office for a teen dealing with a family member diagnosed with cancer,” Robinson says. “It could be easily referenced as a resource in other situations, too.”

Robinson is still thinking through creative ways to include additional information in the game, beyond the main storyline.

“You could pull it from the sidebar on your phone, or you could zoom in on a poster on the wall,” he says. “It could also appear on a bookshelf in the doctor’s office, but we don’t want people to miss particular information on a certain playthrough.”

Robinson and Abraham are also working on including audio for visually impaired users and language translations. Once the functional game prototype is ready later this year, the youth advisory board will review it and provide feedback on its strengths and weaknesses. In-game analytics will measure what people are doing within the game while it’s being tested and reviewed, providing more data to refine the final game.

When all feedback is incorporated, Abraham is prepared to begin sharing the game with teens and hopes to partner with schools, youth after school programs, and oncology clinics to pilot test the game.

“Our ultimate goal is to educate teens and help them make healthy choices,” says Abraham. “We want them to have these basic facts, understand the process of diagnosis and the role genetics play, and facilitate early screening treatment to hopefully reduce the occurrence of cancer.”