Leo Vinton Butts ‘1920 was the first known African-American graduate of the University of Wisconsin School of Pharmacy, as well as the first known African-American to appear in a game for the UW varsity football team.

The son of one of Madison’s earliest African-American residents, he served his country during World War One; he was a civil rights activist; he owned and operated a pharmacy; he represented his schools on the football field; and, in his UW Ph.G. thesis, he was one of the first researchers to attempt to record the history and the contemporary status of African-Americans in the profession of pharmacy.

In the course of writing his groundbreaking thesis, “The Negro in Pharmacy,” however, Butts had trouble uncovering relevant information, and he lamented the lack of available resources that documented the work of African-American pharmacists:

The library of the University of Wisconsin contains one of the best, if not the best, and largest pharmaceutical libraries in America. It is replete with all kinds of pharmaceutical literature, historical, scientific, and commercial, yet in all this library there is scarcely a reference to the negro in pharmacy.

Despite the difficulty of his research, Butts explained his dogged pursuit of his topic: “It was with the idea of bringing together what scattered data I could find in order to learn something more of the people of my own race in my chosed [sic] profession that this thesis was attempted.”

This website tells the story of and honors the memory of Leo Vinton Butts, a scholar, athlete, soldier, activist, historian, pharmacist, proud African-American, and a true Badger pioneer.

Click on the acordion tabs below to read about the life and careers of Leo Butts.

-Gregory Bond, PhD

American Institute of the History of Pharmacy

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Growing up in Madison

Leo Butts’ father, Benjamin “Benny” Butts, was born into slavery in the state of Virginia. During the Civil War, the elder Butts escaped to the camp of the Wisconsin 5th Regiment, which adopted the 13-year old Benny as the unit’s “mascot.” At the end of hostilities, Benny traveled back to Wisconsin with the 5th regiment, and, by 1870, he lived in Madison and operated a popular downtown barbershop. About 1900, Benny Butts took a position as the head messenger at the Wisconsin Historical Society, a job he would keep for the next three decades.

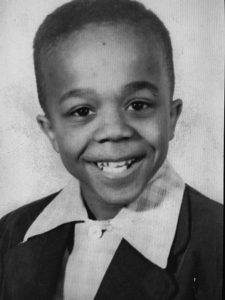

Leo Vinton Butts, the second youngest of Benny and Amy Butts’s five children, was born on January 14, 1898. For much of his childhood, the family lived at 639 East Dayton Street, and, in 1913, Leo entered Madison High School – the now defunct Madison Central High School. From his freshman year, Butts was active in intramural and inter-scholastic sports on campus, participating in class football and track and varsity basketball and football.

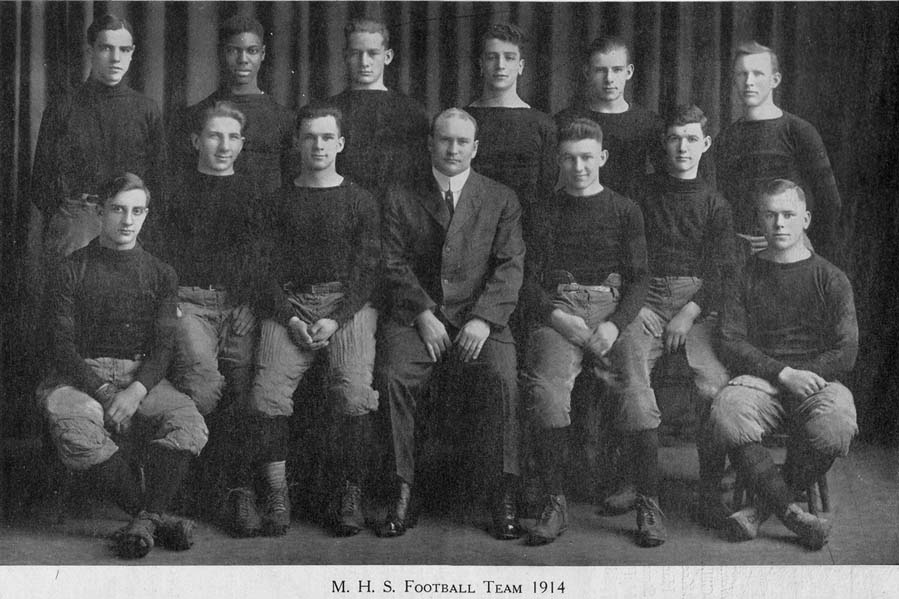

He found his greatest success on the gridiron, and he earned three varsity letters in football at Madison High School. A tall and imposing lineman, Butts often won praise from local sportswriters for his blocking and tackling prowess. The Wisconsin State Journal routinely praised him as a “star lineman” or a “star tackle” and, in 1915, the newspaper called him simply “the best lineman on the Madison team.”

Butts seems to have been well accepted on the football squad and at Madison High School, though he was also sometimes starkly reminded that he was one of the few non-white students at the school. In 1914, during his first season on the varsity squad, Madison traveled to Oshkosh for an away game and stayed at a local hotel the night before the contest. Early in the morning, the upperclassmen on the squad hazed the team’s newcomers with pillow fights and water fights. As they organized their conspiracy, the hazers adopted the potentially inflammatory name of the “Klu Klux Klan.”

Later that year, Madison High School’s annual yearbook, the Tychoberahn described the festivities: “Toward the break of day the Klu Klux Klan, composed of the ‘vets’ of the squad started ‘making the rounds.’ Pillows and tumblers of water were exchanged freely between the Klan and the ‘supposed slumberers.’ That sure was ‘one wonderful night.’”

There is no evidence that Butts, himself, was a specific target of the hazing or that the upperclassman had any particular racial motivations behind choosing the provocative name of the then-popular and politically powerful organization, but one wonders how Butts felt about his teammates adopting the name of the notoriously racist and nativist Klu Klux Klan for their hazing activities.

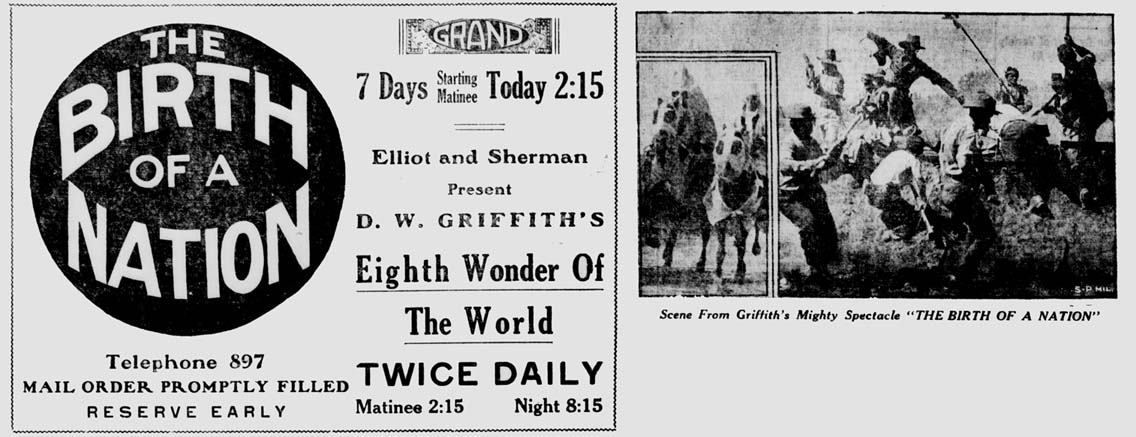

Perhaps in response to such incidents, Butts was active in Madison’s African-American and civil rights communities. In February 1916, D. W. Griffith’s controversial film “Birth of a Nation,” which glorified the Klu Klux Klan’s Reconstruction-era violence and terrorism against African-Americans, played for a week in Madison at the Grand Theater at 206 State Street.

Representatives from Madison’s black community, including 18-year old high school junior Leo Butts, visited Mayor Adolph Kayser to protest the film’s opening. Butts was the youngest member of the protest committee that also included UW student Victor C. Turner, William M. Miller, a janitor at the State Capitol, and other local activists. The Mayor was not sympathetic to their cause, declaring that “he did not want to enter into any legal controversy with the promoters of the show… [and] did not see how he could censor the film.”

Such protests did not seem to have much effect on the popularity of the movie. The Wisconsin State Journal later reported that, during its week’s engagement, the movie had attracted 22,000 people. The State Journal elaborated that “‘The Birth of A Nation’… is believed to have broken all records for attendance at any standard attraction. People from a radius of fifty miles of Madison came in to see the spectacle.”

Despite the protesters’ inability to stop the film, Butts had his first experience with civil rights and racial activism that he would pursue throughout his life. In 1917, Butts, one of the few African-American students in his class, graduated from the science course at Madison High School. Next to his senior class picture, the editors of the annual yearbook wrote: “Courteous and kind he was, and willing too.”

-Gregory Bond, PhD

American Institute of the History of Pharmacy

Attending UW

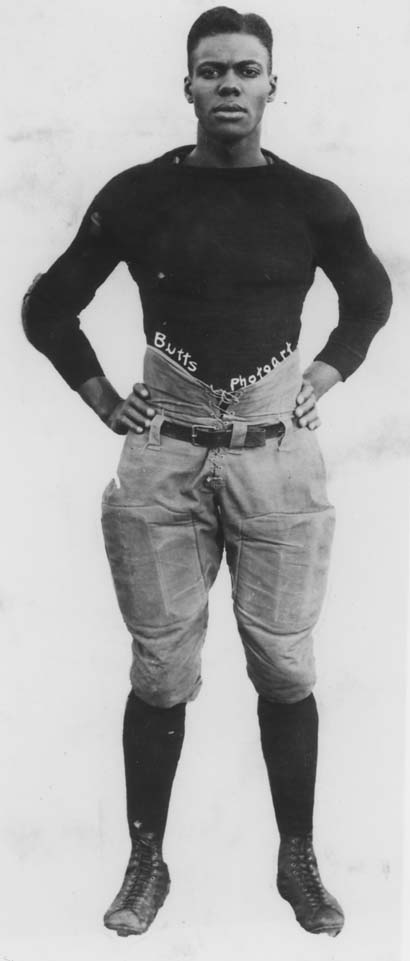

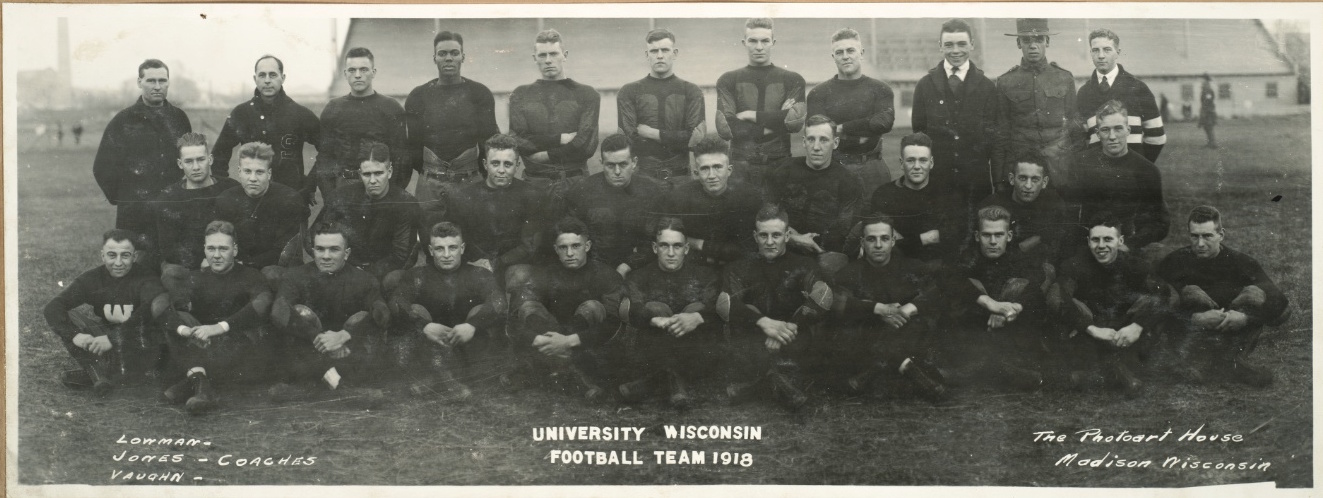

After graduating from Madison High School, Leo Butts enrolled at the University of Wisconsin School of Pharmacy in September 1917, becoming the first known African-American to study pharmacy at UW. During his second year on campus, Butts continued his trailblazing ways and answered the call for football candidates in 1918.

Due to wartime travel restrictions and an influenza epidemic throughout the Midwest, the season got off to a late start, and the Badgers played an abbreviated slate of only six contests. In the second game of the campaign, a 21-0 victory over Beloit College on November 2nd, Butts entered the lineup as a substitute right guard, becoming the first known African-American Badger to participate in a varsity football game. It is unclear whether Butts appeared in the rest of the contests on the schedule, but he proved valuable enough to be selected as one of only four substitute linemen to make the traveling squad for the two road games at Minnesota and Ohio State.

In 1918, Butts enlisted in Company C of the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) that was stationed at the University of Wisconsin. Men who voluntarily joined the SATC were inducted into the United States Army and combined their academic studies with 12 hours per week of military instruction and three hours per week studying “war aims.” SATC students planned to be on campus for three to six months before beginning their service in the armed forces.

Acting UW President E.A. Birge explained the campus SATC presence in the December 1918 issue of the Wisconsin Alumni Magazine: “The students who come to college are to be retained months rather than years. They are enlisted as privates in the Army and receive subsistence and lodging from the University, as well as education, and the Government pays for all of this…. Thus,” Birge concluded, “the war has come to Wisconsin and has profoundly modified our daily life and daily work.”

Butts served in the SATC from October 8, 1918 until he was honorably discharged when the UW SATC was disbanded on December 14, 1918 after the end of World War One. Butts’ football and military commitments had cut into his studies at the UW School of Pharmacy, and he did not return to the gridiron for the Badgers in subsequent seasons, opting to focus on his academic career.

Butts lived at home with his parents while at UW and worked part-time as a clerk in the Park Hotel Pharmacy. During his time in college, Butts also met Alice Emma Phillips, an African-American student from Illinois. Phillips graduated from Champaign High School in 1914 and attended the University of Illinois for two years, before enrolling at the University of Wisconsin in 1917. During her time in Madison, Phillips lived down the street from the Butts family, and she and Leo Butts began dating at some point during their time on campus.

In August 1920, Butts completed the requirements for his degree and graduated from the UW School of Pharmacy. Butts’ thesis “The Negro in Pharmacy” was one of the first scholarly efforts to research the status of African-American pharmacists.

-Gregory Bond, PhD

American Institute of the History of Pharmacy

The Negro in Pharmacy 1 (Secondary Sources)

In the early twentieth century, all candidates for the Ph.G. (Graduate in Pharmacy) degree from the UW School of Pharmacy were required to write a senior thesis in order to graduate. Faculty members accepted a wide range of topics, and Leo Butts chose to research and write about a topic of personal interest, the history of and the contemporary status of African-American pharmacists. He likely found support and encouragement from his thesis advisor, Nellie Wakeman, who, as the first female instructor at the UW School of Pharmacy, undoubtedly understood the challenges that members of underrepresented communities faced in the profession.

View the complete pdf copy of Butts’ thesis

From the beginning, Butts had difficulty finding research, data, or even basic information about African-American pharmacists. In the introduction to his thesis, he lamented that “the library of the University of Wisconsin contains one of the best, if not the best, and largest pharmaceutical libraries in America. It is replete with all kinds of pharmaceutical literature, historical, scientific, and commercial, yet in all this library there is scarcely a reference to the negro in pharmacy.” In his note on sources, Butts elaborated that “the collection of material for this paper has been a difficult task. There is almost no literature on the subject.”

At the time, most academics at predominantly white institutions and most mainstream national pharmacy organizations did not consider topics related to African-Americans worthy of serious study. Edward Kremers, the Dean of the UW School of Pharmacy and a pioneering historian of pharmacy, was representative of many of his contemporaries. In his groundbreaking 1916 book, A Bibliographic Guide for Students of the History of Pharmacy, Kremers included no material about pharmacy instruction at historically black colleges and universities or about African-American pharmacy organizations. His only reference to blacks in pharmacy was in a “Supplement” to his “Periods of General History” classification scheme. Under “semicivilized and barbaric peoples” he listed “the American Indian” and “the Negro,” but, even here, he provided no sources or bibliographic citations for interested researchers.

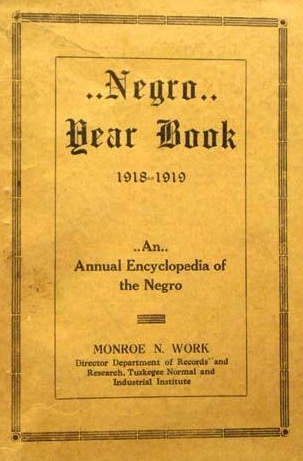

Luckily for Leo Butts, there were a few readily available sources produced by African-American scholars and organizations that he utilized in writing his thesis. Most importantly, he relied on information from the annual Negro Year Book published by Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, which gathered facts, statistics, and information about African-Americans in an almanac-like publication. He also found relevant material in catalogues from the three contemporary schools of pharmacy at historically black institutions: Howard University, Meharry Medical College, and the University of West Tennessee.

Butts also gathered together material about pharmacy organizations run by and for African-Americans, like the National Medical Association, which served black physicians, dentists, and pharmacists, as well as other state, regional, and local pharmacy associations. He argued that such African-American pharmacy organizations could play an important role in serving the black community.

These organizations, Butts wrote, should “educate the colored pharmacists to a point where they realize their duties in the matter of teaching the colored populations the necessity of making their homes more sanitary and hygienic.” He criticized the “deplorable” and unhealthy conditions in some black neighborhoods, and argued that African-American “druggists through advertising and object lessons as well as by simply talking to the people may do much to improve these conditions and thus not only better themselves financially, but render an inestimable service to the colored race.”

-Gregory Bond, PhD

American Institute of the History of Pharmacy

The Negro in Pharmacy 2 (Primary Sources)

Although Leo Butts was able to compile some important information using the available reference sources, he sought to supplement his research by corresponding with prominent African-American pharmacists and educational and pharmacy organizations. Unfortunately, most of the letters he received in response—which he included as appendices in his thesis—were unable to provide any useful information.

Butts did find one informative correspondent: Dr. Edward F. Harris, the Pharmaceutical Editor of the Journal of the National Medical Association. Harris wrote a long and thoughtful response encouraging Butts’ study. “I am indeed glad,” Harris wrote, “that some or our race think enough of our profession to prepare some literature thereupon.” Harris provided useful statistics about the number of African-American pharmacists and drugstores and also related several anecdotes about African-American pharmacists.

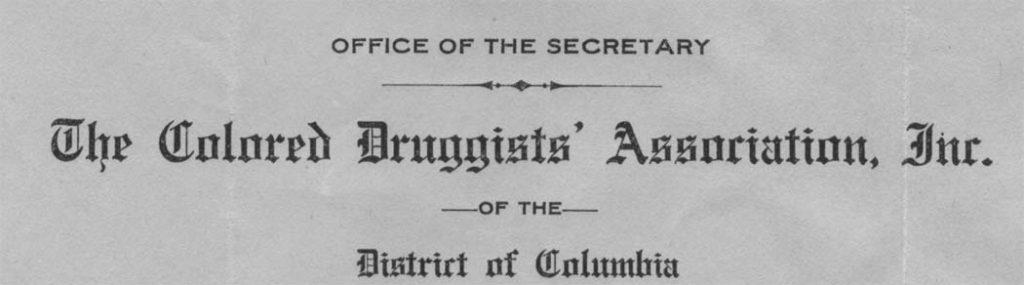

Harris also informed Butts about the Colored Druggists’ Association of the District of Columbia, a cooperative organization for African-American pharmacists in D.C. Harris claimed it was the only such association of black druggists in the country, and Butts explained the utility of the organization: “In Washington, where there is considerable antagonism between the negro and white races, it is especially important. It is through this cooperative plan of purchasing and the consequent ability of the negro druggist to place the best quality of goods upon the market at the lowest retail prices that he is able to compete successfully with the white pharmacists.”

In addition to urging cooperation among African-American pharmacists, Butts also advocated a better working relationship between black physicians and black pharmacists, which, he wrote “should be one of mutual help and co-operation stimulated by racial pride as well as a true spirit of helpfulness.” Butts lamented that “unfortunately this is not always the case” and explained that some black doctors steered their customers away from African-American pharmacists. “It is difficult to understand this attitude on the part of negro physicians,” he declared and wrote angrily that “they are discrediting not only the colored pharmacists but the whole colored race, and, most of all, themselves.”

At the end of the introduction to his thesis, Butts explained the motive behind his project. “It was with the idea of bringing together what scattered data I could find in order to learn something more of the people of my own race in my chosed [sic] profession that this thesis was attempted.” After completing his research, Butts decided that pharmacy was a promising profession for African-Americans. “The field for colored pharmacists in retail pharmacy is large and almost untouched,” he observed. “There should be an opportunity here for all who receive the necessary training.”

View the complete pdf of Butts’ thesis.

-Gregory Bond, PhD

American Institute of the History of Pharmacy

Gary, Indiana

Leo Butts graduated from the UW School of Pharmacy in August 1920, and, two months later, he received his certification from the State Board as an assistant pharmacist. By 1922, he and Alice Emma Phillips had moved to Gary, Indiana where they were married on August 30, 1922. The following year, Butts passed the Indiana State Board examination and quickly found work as a pharmacist at the Green Drug Company. Alice Phillips Butts soon began her long career as a teacher in the Gary public schools at the local Theodore Roosevelt High School.

Throughout the 1920s, Leo and Alice Butts would frequently return to Madison to visit family, and, in 1926, they had an extended return to Madison while Alice Butts took classes at the UW summer session. On August 2, 1924, the couple’s only child, Alice Leota Butts, was born.

The Great Depression was a challenging time for the Butts family. In 1930, due to the economic downturn, Leo Butts lost his job as a pharmacist, but he was soon able to find work as a mail carrier for the United States Postal Service.

Although he was no longer working in his chosen profession, Butts took his new job seriously, and he was active in the local chapter of the National Alliance of Postal Employees, a union for African-Americans in the USPS. Tragedy soon struck the Butts family, though, and in 1936, daughter Alice Butts died of a heart infection just three months past her twelfth birthday.

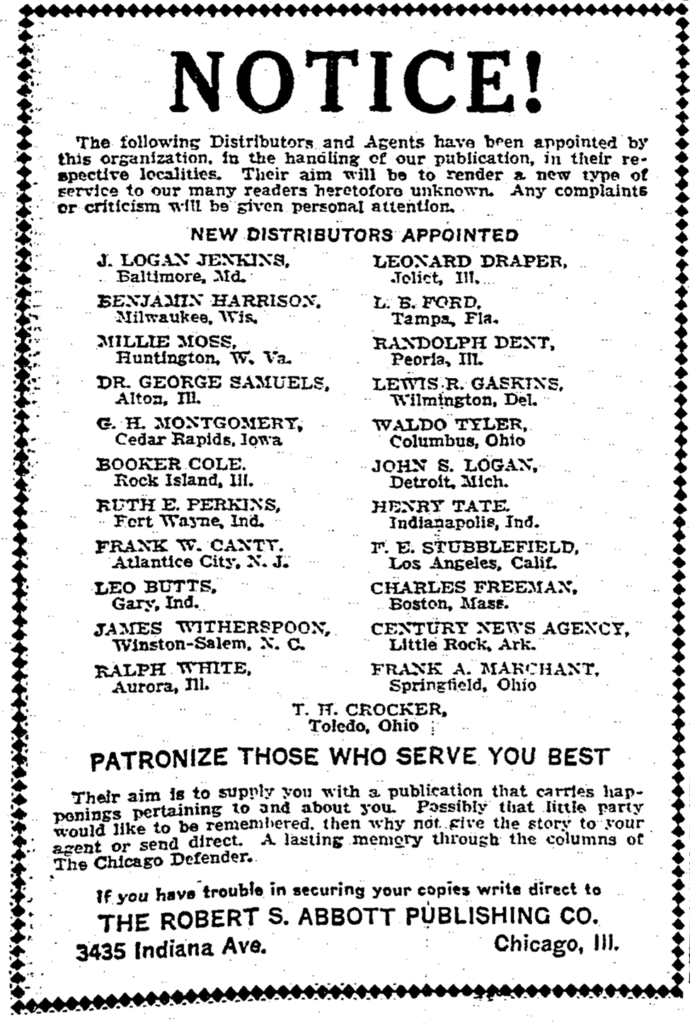

Despite these difficulties, Leo Butts continued to be active in his community. In 1934, Butts became Gary’s official distributor and agent for the Chicago Defender, a national weekly African-American newspaper that strongly advocated for civil rights and equal opportunity.

He was also a leader of Gary’s Calumet American Legion Post no. 99, reportedly “Indiana’s largest colored post of the American Legion.” In 1935, Butts was elected Commander of the Calumet post, and, that same year, under his leadership, the post organized a free clinic at the local St. John’s Hospital during Negro Health Week. Fittingly, due to his interest in African-American history, Butts was the chairman of a meeting during the week that, in addition to showing “motion pictures dealing with the prevention of disease,” featured a historical program commemorating Booker T. Washington and the founding of Negro Health Week.

Author Denver E. Long, who grew up in Gary, remembered the Owl Drug Store as a popular destination, recalling that Sundays after church “meant dressing up in my ‘Sunday clothes’ and hanging out with friends on the corner at Mr. Butts’ Owl Drug Store after services, drinking nickel cokes and looking forward to the afternoon trip to the movies or to the rolling skating rink.” Denver Long also worked at the Owl Drug Store, and he has fond memories of his time working for Leo Butts:

Sometimes customers would drop money over the counter and behind the ice cream freezers, and it was my job to crawl between the counter and the freezer to retrieve the money. Much of the found money was covered with sticky, syrupy goo that I could collect, soak in warm water, and have for my pocket money. I got paid $1.00 every Saturday before closing, and, during Christmas, I’d get an extra dollar bonus plus any candy that I wanted. A dollar was a lot of money.

One endearing thing that I remember most about Mr. Butts was that he had BIG hands. But he was a very kind man to me and pretty much gave me the run of the store even though my job was to clean it. I never knew until now about his background or history as an athlete and civil rights activist. Mr. Leo V. Butts was a friendly giant, and he was my dear friend.

— Denver E. Long, BFA, MA, DPAKR

Butts ran the Owl Drug Store until his death in 1956 from a heart ailment. He was buried in Gary’s Fern Oaks Cemetery. Alice Phillips Butts lived until 1980 and was buried next to her husband.

Unfortunately, Leo Butts’ life after his graduation from the University of Wisconsin is not well documented and information about his careers in Gary, Indiana is scarce. We would be very interested in hearing from anybody with additional biographical material about or photographs of Leo Butts or of the Owl Drug Store.

-Gregory Bond, PhD

American Institute of the History of Pharmacy