Alumni blend love of animals, pharmacy to specialize in animal medicine

By Katie Gerhards

Photos by Todd Brown

Have you ever tried to make a cat swallow a pill? Even the thought of the delicate procedure conjures images of sharp teeth, sharper claws, and a soggy pill flying through the air—likely never to be found again. There has to be a better way.

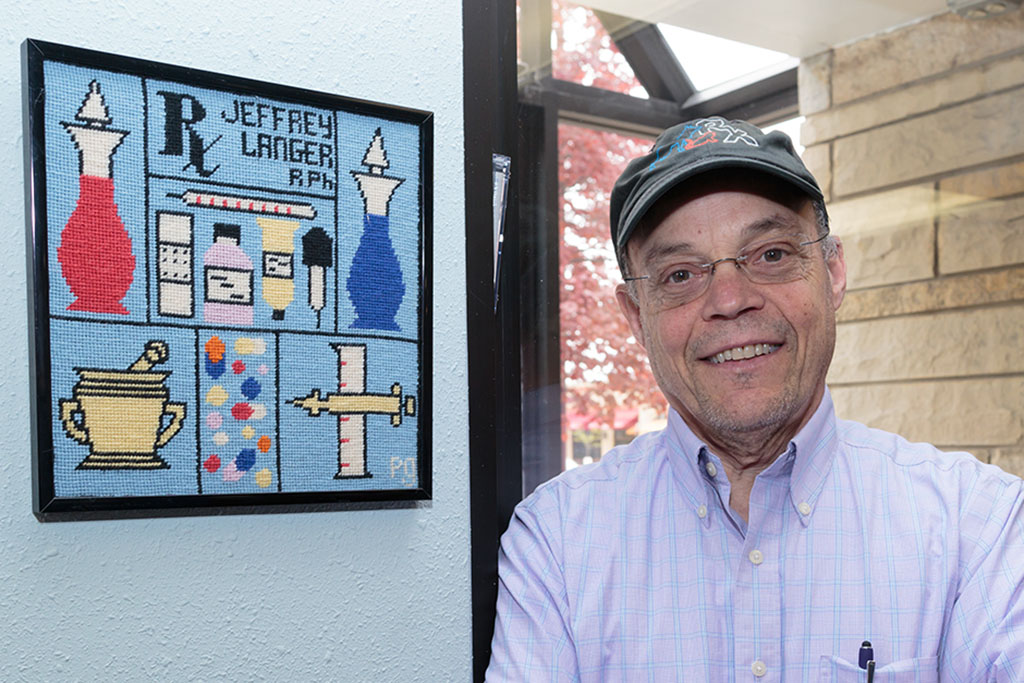

That’s one nagging thought that spurred Jeff Langer (BS ’76) to leverage his training as a pharmacist to embark on a non-traditional career path: animal pharmacist.

“Being a pet owner, I knew it was hard to give them medications. For our cat—Tera, short for Terrible—it was just about impossible,” says Langer. “As pharmacists, Patti and I came up with some alternative ways to do it, and after that, it was just a no-brainer.”

For example, if your cat doesn’t want to swallow a capsule, the medication can often be made into a paste and spread on the cat’s fur, and they’ll lick the medicine through grooming. “You have to consider the medication, the stability of the medication, how the pet grooms or eats, what their flavor preferences are, and all of the contraindications that come with diseases, just like for humans,” says Langer.

“When you see a problem in the world, it might be easy to keep going down the beaten path, but that’s not the way I live my life.” –Jeff Langer

Langer and his wife, Patti (BS ’78), both graduates of the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy, opened the Pet Apothecary in Milwaukee, Wis., in 1999. Today, their innovative business works closely with zoos, humane societies, emergency clinics, and veterinarians around Wisconsin and Illinois and has treated hundreds of different species.

A pharmacists’ license for human medicine also enables Langer to provide pharmacy services for animals, and his degree from the School of Pharmacy prepared him well to take on this niche role. But that’s not to say that there weren’t many steps between graduating from the School and becoming the Midwest’s pet medication specialist.

Foundations in pharmacy

For Langer, pharmacy is practically a family tradition. In addition to his wife, his father, grandfather, cousin, and uncle are also pharmacists, and much of his childhood was spent helping out in the family pharmacy. “I don’t ever remember thinking about it,” says Langer. “I just knew I was going to be a pharmacist.”

After earning his pharmacy degree at UW–Madison, Langer started graduate school under Professor George Zografi, then dean of the School of Pharmacy, studying pharmaceutical dosage formulation.

Every year, graduate students present their research to each other. “I was very intimidated by the other grad students. They were all close to finishing their PhD, and I was an incoming doctoral student,” Langer says. “I didn’t want a lot of questions, so I tried to pick a topic they wouldn’t be interested in: formulating medications for ruminant animals.”

Zografi liked the idea, because ruminant animals—such as cows, goats, and deer that ferment a mash of plant matter in their stomachs before digestion—have drastically different stomachs that require different types of medication. With the topic approved, Langer dove in and researched how ruminants digest products and how medication affects them differently.

“I learned a lot and gained an appreciation for treating large animals,” he says. “And I didn’t get any questions—so it worked like a charm.”

Although he liked his field of study, after his first year in the graduate program, Langer felt a pull to return to community pharmacy practice and was hired by Marty Stein (BS ’59), who founded Stein Drugs in Milwaukee, and also continued to work in his father’s pharmacy: Jack Langer Pharmacy and Gifts.

“For my whole life, I worked for my father and grandfather in retail, and I came to really like constant patient contact,” Langer says. “Working in the lab was intellectually stimulating, but it wasn’t satisfying. I’m a people person.”

Trials in entrepreneurship

Despite his research with ruminant animals, Langer says he never pictured himself becoming a veterinary pharmacist—that was never the plan. But the opportunities continued to present themselves until all of the pieces fell into place.

While he was practicing in his father’s pharmacy, they developed a small compounding practice to fill prescriptions for dermatologists and other specialists, including veterinarians, who would occasionally call for advice. “I really jumped on that,” says Langer. “I really liked working with them, so I visited a few animal clinics to try to develop a larger relationship there.”

Because veterinarians relied on dispensing medications as a large part of their business, the timing wasn’t yet right for a partnership, but Langer did end up working with a handful of vets, and that planted a seed in his head that would continue to germinate for more than a decade.

In 1993, Langer and his wife bought his father’s pharmacy and opened two more locations around the Milwaukee area. “It was a bit more than we could handle,” he says. And after a year and a half, they decided to sell all three.

“Sometimes you learn by failure. It’s the hardest teacher, but it’s also the best teacher,” Langer says. “Every time I made a mistake, I tried to fix it so that I would never make that same mistake again, and that went for every part of my practice.”

After the sale, he went from working 80 to 90 hours a week running his pharmacies to just 40 hours. After five weeks of that scaled-back schedule, Langer began to get restless.

“He used to be gone 12 or 13 hours a day working for his dad all of those years, even before we opened the other pharmacies,” says his wife, Patti. “He’s the kind of person who needs more to do than work for 40 hours a week.”

She had five words for him: “Find something else to do.”

Fortunately, the restrictive covenant that accompanied the sale of his pharmacies left him an opening: He couldn’t practice in human medicine as a competitor—but that’s it.

An unmet need

“He’d already been compounding for animals for years, so we had a pretty good idea that there was a need for it,” says Patti. “But we never anticipated what eventually came out of it.”

While he was a licensed pharmacist, there was still much for him to learn about medications for animals, so he started pounding the pavement—and hitting the books—to learn more.

“My education at the UW–Madison School of Pharmacy was very good, and it gave me the majority of what I needed to know to work with pets, but veterinary pharmacy is a specialized area. There are several medications in animal use that aren’t used in humans, and vice versa,” says Langer. “For example, humans don’t eat grass, so we don’t get a lot of parasites or outdoor illnesses compared to animals.”

In addition to brushing up on anti-parasitic medications, he also visited veterinary schools, zoos, and emergency clinics to learn more about animal medications until he felt comfortable for the big launch of his next venture.

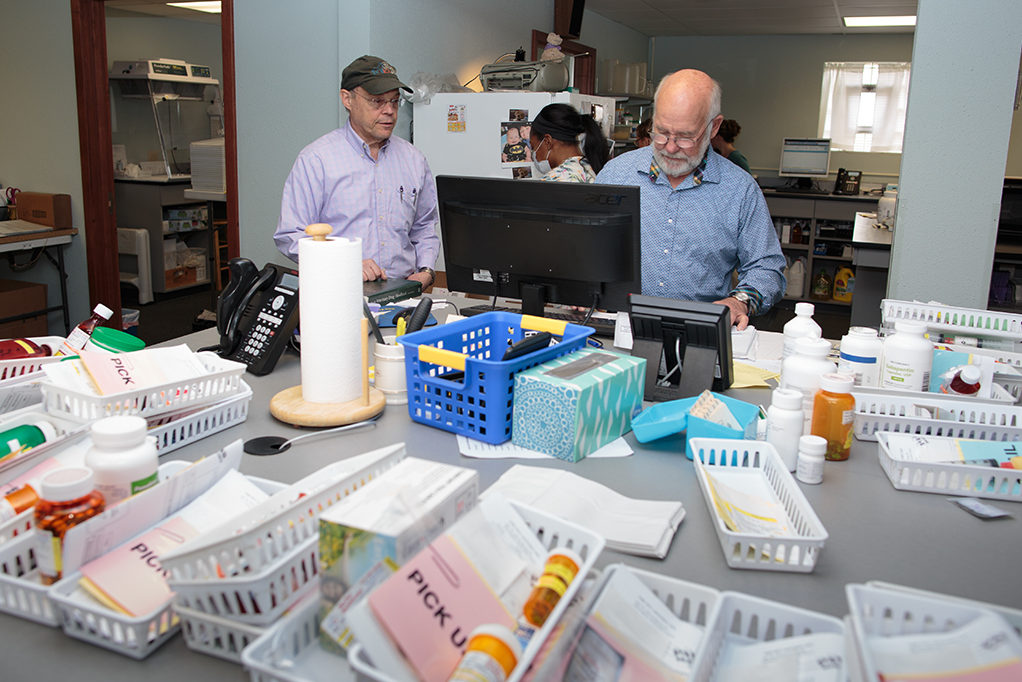

Since opening in 1999, the Pet Apothecary has had a steady stream of business.

“The market for compounding for animals was wide open,” says Langer. “The first thing I did was go to veterinarians and try to allay their fears about a pharmacist taking over their medication dispensing and show them how we would give them a double-check on their prescribing, make sure the drug matched the disease, and that the dosage they ordered was properly dispensed—just like a regular pharmacist.”

For the first five years, the couple operated the business out of their basement in their spare time. Jeff was still working part-time at one of the pharmacies he’d sold, and he didn’t leave to go full-time at the Pet Apothecary for nearly 10 years. Patti, on the other hand, kept her steady job as an out-patient pharmacist.

A few veterinarians were willing to give him a shot initially, and slowly more kept getting in touch. Today, Langer treats a menagerie of dogs, cats, llamas, snakes, horses, lizards, and more. Although he doesn’t work with food source animals, he does help the occasional show pig or cow.

“Some days, we’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, we just made banana-flavored antibiotics for a monkey,” says Patti. “It’s incredible.”

And as veterinarians move around, they take the Langers’ service with them, which has helped the business expand to cover Wisconsin and Illinois—the two states Langer is licensed to practice.

“It’s been nothing short of amazing,” Patti says. “Veterinarians and pet owners are just different kinds of people, and it’s not often that you run into one who isn’t nice.”

Thinking outside the box

Opening the Pet Apothecary wasn’t the first—or likely the last—time Langer leveraged his entrepreneurial spirit and background in pharmacy.

When he started practicing in the 1970s and ‘80s, HMOs were just getting their start. “Pharmacists were being phased out of participation in HMOs because there were no laws preventing them from starting their own pharmacy or contracting with chains, but there were no organizations pushing for HMOs to work with independent pharmacists,” Langer says.

“It’s been nothing short of amazing. Veterinarians and pet owners are just different kinds of people, and it’s not often that you run into one who isn’t nice.” –Patti Langer

After contacting a few pharmacist friends, he started a company called Wisconsin Independent Pharmacy Association, which linked pharmacists together to contract with HMOs, much like a chain pharmacy. “We worked together for 10 or 15 years, and I take great pride in the fact that we tried to help independent pharmacists keep their doors open to keep serving the public,” he says. That partnership eventually became RESTAT.

“Without people thinking outside the box, we wouldn’t have yo-yos, hula hoops, or computers,” he says. “When you see a problem in the world, it might be easy to keep going down the beaten path, but that’s not the way I live my life.”

Read more about how the School of Pharmacy instills entrepreneurial skills in PharmD students.

Learn about the possibilities of a PharmD degree.